Deforestation of the Amazon rainforest

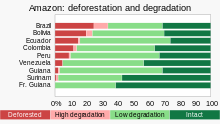

The Amazon region includes the territories of nine nations, with Brazil containing the majority (60%), followed by Peru (13%), Colombia (10%), and smaller portions in Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana.

Illegal logging was cited as a cause by the Brazilian environment minister, while critics highlighted the expansion of agriculture as a factor encroaching on the rainforest.

However, European colonization in the 16th century, driven by the pursuit of gold and later by the rubber boom, depopulated the region due to diseases and slavery, leading to forest regrowth.

[26] In January 2019, Brazil's president, Jair Bolsonaro, issued an executive order granting the agriculture ministry oversight over certain Amazon lands.

According to a 2004 World Bank paper and a 2009 Greenpeace report, cattle ranching in the Brazilian Amazon, supported by the international beef and leather trades, has been identified as responsible for approximately 80% of deforestation in the region.

A study based on NASA satellite data in 2006 revealed that the clearing of land for mechanized cropland had become a significant factor in deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon.

In 2006, several major commodity trading companies, including Cargill, pledged not to purchase soybeans produced in recently deforested areas of the Brazilian Amazon.

The lack of robust regulatory frameworks exacerbates the vulnerability of these areas to exploitation, creating a multifaceted threat to the Amazon's biodiversity and local communities.

In December 2023 the lower house of the Brazilian Congress approved a bill aiming to pave again the high way BR-319 (Brazil highway), what can threaten the existence of the rainforest.

The bill defines the road as “critical infrastructure, indispensable to national security, requiring the guarantee of its trafficability,”[54] Mining is a significant contributor to the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest.

[11] During the early 2000s, deforestation in the Amazon rainforest showed an increasing trend, with an annual rate of 27,423 km2 (10,588 sq mi) of forest loss recorded in 2004.

Between August 2017 and July 2018, approximately 7,900 km2 (3,100 sq mi) of forest were deforested in Brazil, representing a 13.7% increase compared to the previous year and the largest area cleared since 2008.

The National Institute for Space Research (INPE) in Brazil estimated that at least 7,747 km2 (2,991 sq mi) of the Brazilian Amazon rainforest were cleared during the first half of 2019.

Modeling studies have suggested that deforestation may be approaching a critical "tipping point" where large-scale "savannization" or desertification could occur,[71] leading to catastrophic consequences for the global climate.

[76] According to a research led by Elena Shevliakova and Stephen Pacala complete deforestation of the Amazon will cause a global temperature rise of 0.25 degrees.

[80] The deforestation of the Amazon rainforest has had a significant impact on Brazil's freshwater supply, particularly affecting the agricultural industry, which has been involved in clearing the forests.

[84][85] In 2019, a group of scientists conducted research indicating that under a "business as usual" scenario, the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest will lead to a temperature increase of 1.45 degrees in Brazil.

They stated that this temperature rise could have various consequences, including increased human mortality rates and electricity demands, reduced agricultural yields and water resources, and the potential collapse of biodiversity, especially in tropical regions.

[86] According to another research, complete Amazon deforestation will render the region itself (including 7 million square kilometers, 9 states in Brazil and 8 other countries) more or less uninhabitable as the temperature will rise by more than 4.5 degrees and rainfall will be reduced by a quart.

In early 2019, Brazil's newly elected president, Jair Bolsonaro, issued an executive order empowering the agriculture ministry to regulate the land occupied by indigenous tribes in the Amazon.

Such policies provide indigenous communities with the legal authority to protect their land from encroachment and exploitation, creating a powerful tool for combating deforestation in the Amazon.

[93] In 2012, the Yanomami organization HORONAMI expressed their concerns, stating, “Illegal miners persist in destroying our lands, and the government must act urgently to stop these abuses and investigate the harm being done in the Upper Ocamo region”.

In 2020, a report from Mongabay quoted the Yanomami leaders expressing frustration with Brazilian authorities, stating, “We feel utterly abandoned; the government turns a blind eye to the illegal activities that poison our rivers and bring disease to our people”.

[97] In September 2015, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff addressed the United Nations, reporting that Brazil had effectively reduced the deforestation rate in the Amazon by 82%.

[98] In August 2017, Brazilian President Michel Temer revoked the protected status of an Amazonian nature reserve, which spanned an area equivalent to Denmark in the northern states of Pará and Amapá.

[99] In April 2019, an Ecuadorian court issued an order to cease oil exploration activities in an area of 1,800 square kilometers (690 sq mi) within the Amazon rainforest.

[102][103][15] Bolsonaro has rebuffed European politicians' attempts to intervene in the matter of Amazon rainforest deforestation, citing it as Brazil's internal affairs.

[111] In August 2023, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva hosts a summit in Belem with eight South American countries to coordinate policies for the Amazon basin and develop a roadmap to save the world's largest rainforest, also serving as a preparatory event for the COP30 UN climate talks in 2025.

[115] In September 2024, Sawré Muybu, an indigenous land, belonging to the Munduruku people got an official recognition, which is considered as a significant step in fighting deforestation.

[116] According to the Woods Hole Research Institute (WHRC) in 2008, it was estimated that halting deforestation in the Brazilian rainforest would require an annual investment of US$100–600 million.