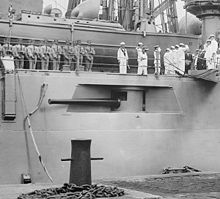

Delaware-class battleship

With this class, the 16,000 long tons (16,257 t) limit imposed on capital ships by the United States Congress was waived, which allowed designers at the Navy's Bureau of Construction and Repair to correct what they considered flaws in the preceding South Carolina class and produce ships not only more powerful but also more effective and rounded overall.

With these ships, the US Navy re-adopted a full-fledged medium-caliber weapon for anti-torpedo boat defense.

Propulsion systems were mixed; while North Dakota was fitted with steam turbines, Delaware retained triple-expansion engines.

Direct-drive turbines were much less fuel-efficient, a significant concern for a Navy with Pacific responsibilities but lacking Britain's extensive network of coaling stations.

In contrast, North Dakota remained on the American coast throughout the war, due in part to worries about her troublesome turbine engines.

Prompted by the launch of and misinformation about HMS Dreadnought, the US Navy and Congress faced what they perceived as a vastly better battleship than the two South Carolina battleships then under construction, which were designed under tonnage constraints that Congress had imposed on capital ships.

While the C&R design was considered superior, it still came under criticism, particularly for the poor placement of, and lack of protection for, the secondary armament.

[6] The Delawares were significantly more powerful than their predecessors, the South Carolina-class, and are mentioned by Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships as the first to match the standard set by the British with Dreadnought.

[6] This was due in large part to the elimination of Congressional limits on the size of new battleships; the only restriction the Congress placed on their design was that the cost of hull and machinery could not exceed 6 million USD.

[9] For reasons including expected hostilities with Japan, requiring travel across the Pacific Ocean, long operational range was a recurrent theme in all US battleship designs.

However, this penchant for reliability came under question in the late 1930s as battleships with reciprocating engines performed poorly in the Pacific.

[15][11] Another challenge with the main armament was that its weight, 437 long tons (444 t) per turret,[14] which had to be spread over much of the hull, led to increased stress on the structure.

The closer the weight of the heavy guns to the ends, the greater the stress and risk for structural failure due to metal fatigue.

High speed required fine ends, which were not especially buoyant, and the amount of space needed amidships for machinery precluded moving the main turrets further inboard.

Not having to worry about a displacement limit allowed Capps the option of deepening the hull, which helped to some extent.

He added a forecastle to allow for better seakeeping and to make room for officers' quarters and restored the full height of the hull aft.

[1] The Naval War College in its 1905 Newport Summer Conference considered the 3-inch (76 mm) guns fitted to the South Carolina class too light for effective anti-torpedo-boat defense.

A committee on this issue formed during the conference suggested that a gun with a high velocity and flat trajectory would work best—one powerful enough to smash an attacking vessel yet light enough for easy handling and rapid firing.

[18] While these guns were considered an improvement by the Navy over that of the South Carolinas, their placement remained problematic as even in calm water, they were extremely wet and thus difficult to man.

[15] As with the South Carolina class, these ships were fitted with two 3-inch/50 caliber anti-aircraft (AA) guns in Mark 11 mounts in 1917.

[21] The Bliss-Leavitt 21-inch Mark 3 Model 1 torpedo designed for these tubes had an overall length of 196 in (5.0 m), a weight of 2,059 lb (934 kg) and propelled an explosive charge of 210 lb (95 kg) of TNT to a range of 9,000 yd (8,230 m) at a speed of 27 kn (31 mph; 50 km/h)[22] The armored belt ranged in thickness from 9 to 11 in (229 to 279 mm) in the more important areas of the ship.

[23] During trials, Delaware was run at full speed for 24 hours straight to prove that her machinery could handle the stress.

[24] When the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, Delaware was initially tasked with readiness training off the East Coast.

[24] Late in the year, she was deployed to Europe as part of the US Navy's Battleship Division Nine, under the command of Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman.

Unlike her sister, North Dakota remained off the American coast for the duration of the United States' involvement in World War I.

[26] Hugh Rodman, the commander of the American expeditionary force, specifically requested that North Dakota be kept stateside; he felt her turbine engines were too unreliable for the ship to be deployed to a war zone.

Post-war, North Dakota made a second trip to Europe, primarily to ports in the Mediterranean Sea.

During the visit, the ship was tasked with the return of the remains of the Italian ambassador, Vincenzo Macchi di Cellere, who had died 20 October 1919 in Washington, DC.