Blowback (firearms)

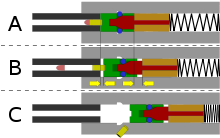

Blowback is a system of operation for self-loading firearms that obtains energy from the motion of the cartridge case as it is pushed to the rear by expanding gas created by the ignition of the propellant charge.

The blowback principle may be considered a simplified form of gas operation, since the cartridge case behaves like a piston driven by the powder gases.

In firearms, a blowback system is generally defined as an operating system in which energy to operate the firearm's various mechanisms, and automate the loading of another cartridge, is derived from the inertia of the spent cartridge case being pushed out the rear of the chamber by rapidly expanding gases produced by a burning propellant, typically gunpowder.

The extent to which blowback is employed largely depends on the manner used to control the movement of the bolt and the proportion of energy drawn from other systems of operation.

"[1] In 1663 a mention is made in the journal of the Royal Society for that year of an engineer who came to Prince Rupert with an automatic weapon, though how it worked is unknown.

[6][7] In 1876 a single-shot breech-loading rifle with an automatic breech-opening and cocking mechanism using a form of blowback was patented in Britain and America by the American Bernard Fasoldt.

[11][12] In 1888 a delayed-blowback machine gun known as the Skoda was invented by Grand Duke Karl Salvator and Colonel von Dormus of Austria.

Yet the bolt must cycle far enough back to eject the spent casing and load a new round, which would limit the return spring to an average force of 60 pounds-force (270 N).[why?]

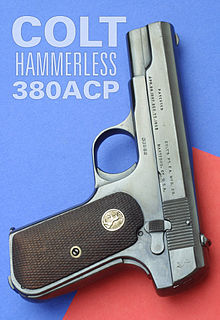

Heavier calibre semiautomatic handguns typically employ a short recoil system, of which by far the most common type are Browning-derived designs which rely on a locking barrel and slide assembly instead of blowback.

In a simple blowback design, the propellant gases have to overcome static inertia to accelerate the bolt rearwards to open the breech.

This sliding motion of the case, while it is expanded by a high internal gas pressure, risks tearing it apart, and a common solution is to grease the ammunition to reduce the friction.

According to a United States Army Materiel Command engineering course from 1970, "The advanced primer ignition gun is superior to the simple blowback because of its higher firing rate and lower recoil momentum.

A slight delay in primer function, and the gun reverts to a simple blowback without the benefit of a massive bolt and stiffer driving spring to soften the recoil impact.

A closed bolt firing equivalent of Advanced Primer Ignition that uses straight-sided rebated rim cartridges in an extended deeper chambering to contain the gas pressure slightly longer until it reaches a safe level to extract.

As with the resistance provided by momentum in API, it takes a fraction of a second for the propellant gases to overcome this and start moving cartridge and bolt backwards; this very brief delay is sufficient for the bullet to leave the muzzle and for the internal pressure in the barrel to decrease to a safe level.

Because of high pressures, rifle-caliber delayed blowback firearms, such as the FAMAS, AA-52 and G3, typically have fluted chambers to ease extraction.

Though appearing simple, its development during World War II was a hard technical and personal effort, as German engineering, mathematical and other scientists had to work together on a like-it-or-not basis led by Ott-Helmuth von Lossnitzer, the director of Mauser Werke's Weapons Research Institute and Weapons Development Group.

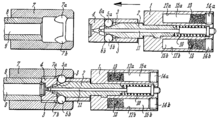

Experiments showed roller-delayed blowback firearms exhibited bolt-bounce as the bolt opened at an extreme velocity of approximately 20 m/s (66 ft/s) during automatic fire.

[27] In December 1943 Maier came up with an equation that engineers used to change the angles in the receiver to 45° and 27° on the locking piece relative to the longitudinal axis reducing the bolt-bounce problem.

Großfuß worked on a roller-delayed blowback MG 45 general-purpose machine gun that, like the StG 45 (M), had not progressed beyond the prototype stage by the end of World War II.

After World War II, former Mauser engineers Ludwig Vorgrimler and Theodor Löffler perfected the mechanism between 1946 and 1950 while working for the French small arms manufacturer Centre d'Etudes et d'Armament de Mulhouse (CEAM).

Their reliable functioning is limited by specific ammunition and arm parameters like bullet weight, propellant charge, barrel length and amount of wear.

The angles are critical and determine the unlock timing and gas pressure drop management as the locking piece acts in unison with the bolt head carrier.

[32] Bearing delay is designed to be tuned based on the user's preference or configuration of other components by swapping to a lifter with a different geometry.

[49][52] John Browning developed this simple method whereby the axis of bolt movement was not in line with that of the bore probably during late WWI and patented it in 1921.

[58] This operation is one of the most simple forms of delayed blowback but unless the ammunition is lubricated or uses a fluted chamber, the recoil can be volatile especially when using full length rifle rounds.

Ordnance Office and later Winchester) developed a mechanism to allow firearms designed for full-sized cartridges to fire .22 caliber rimfire ammunition reliably.

The increased recoil produced by the floating chamber made these training guns behave more like their full-power counterparts while still using inexpensive low-power ammunition.

The GRAU however still gave a negative evaluation of Barishev's gun, pointing out that the main problems with reliability of firearms using the cartridge case as a piston were known since the 1930s and still unsolved.

Whatever actual advantage a clean, unlubricated Blish system could impart could also be attained by adding a mere ounce of mass to the bolt.