Democritus

[b][6] He was a polymath and prolific writer, producing nearly eighty treatises on subjects such as poetry, harmony, military tactics, and Babylonian theology.

[6] We have various quotes from Democritus on atoms, one of them being: δοκεῖ δὲ αὐτῶι τάδε· ἀρχὰς εἶναι τῶν ὅλων ἀτόμους καὶ κενόν, τὰ δ'ἀλλα πάντα νενομίσθαι [δοξάζεσθαι].

Yonge 1853)He concluded that divisibility of matter comes to an end, and the smallest possible fragments must be bodies with sizes and shapes, although the exact argument for this conclusion of his is not known.

[4] Using analogies from humans' sense experiences, he gave a picture or an image of an atom that distinguished them from each other by their shape, their size, and the arrangement of their parts.

Moreover, connections were explained by material links in which single atoms were supplied with attachments: some with hooks and eyes, others with balls and sockets.

The elementary particles are similar to Democritean atoms in that they are indivisible but their collisions are governed purely by quantum physics.

The atomistic void hypothesis was a response to the paradoxes of Parmenides and Zeno, the founders of metaphysical logic, who put forth difficult-to-answer arguments in favor of the idea that there can be no movement.

Democritus held that originally the universe was composed of nothing but tiny atoms churning in chaos, until they collided together to form larger units—including the earth and everything on it.

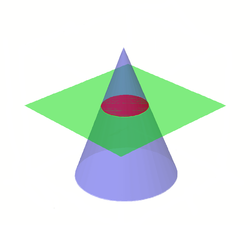

[i][11] Plutarch[j] also reports that Democritus worked on a problem involving the cross-section of a cone that Thomas Heath suggests may be an early version of infinitesimal calculus.

He believed that these early people had no language, but that they gradually began to articulate their expressions, establishing symbols for every sort of object, and in this manner came to understand each other.

He says that the earliest men lived laboriously, having none of the utilities of life; clothing, houses, fire, domestication, and farming were unknown to them.

Democritus presents the early period of mankind as one of learning by trial and error, and says that each step slowly led to more discoveries; they took refuge in the caves in winter, stored fruits that could be preserved, and through reason and keenness of mind came to build upon each new idea.

[13] Later Greek historians consider Democritus to have established aesthetics as a subject of investigation and study,[14] as he wrote theoretically on poetry and fine art long before authors such as Aristotle.

[n] Democritus is evoked by English writer Samuel Johnson in his poem, The Vanity of Human Wishes (1749), ll.

49–68, and summoned to "arise on earth, /With chearful wisdom and instructive mirth, /See motley life in modern trappings dress'd, /And feed with varied fools th'eternal jest."