Demographic history of Palestine (region)

By the early sixth century, Ofer's survey results suggest that around 100,000 lived in the kingdom of Judah, with the population in the central hills, Benjamin and Jerusalem about 69,000.

[10] The Persian province of Yehud Medinata was sparsely-populated and predominantly rural, with around half of the settlements of late Iron age Judah and a population of around 30,000 in the 5th to 4th centuries BC.

[16] Based on analysis of epigraphic material and ostraca from the region, around 32% of recorded names were Arabic, 27% were Edomite, 25% were Northwest Semitic, 10% were Judahite (Hebrew) and 5% were Phoenician.

[23] Coinciding with the account of Josephus, archaeological evidence attests to significant destruction in the urban and rural settlements in Idumaea, Samaria and the coastal cities from the Hasmonean conquests, followed by the resettlement of Jews in the newly conquered territories.

[19] Further north, the Galilee received significant Jewish migration from Judea after its conquest, contributing to a 50% increase in settlements, while the pagan population was greatly reduced.

[25] However, unlike John Hyrcanus, Alexander Jannaeus did not compel the non-Jews to assimilate to the Jewish ethnos and permitted minority ethnē to exist within Hasmonean borders, with the exception of Phoenician coastal cities in the north whom Josephus claims he enslaved.

The Roman occupation encompassed the end of Jewish independence in Judea, the last years of the Hasmonean kingdom, the Herodian age and the rise of Christianity, the First Jewish–Roman War, and the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Second Temple.

[29] Modern estimates vary: Applebaum argues that in the Herodian kingdom, there were 1.5 million Jews, a figure Ben David says covers the numbers in Judea alone.

), which would work out to the limit of a sustainable population of 1,000,000 people, a figure which, Broshi states, remained roughly constant down to the end of the Byzantine period (600 CE).

"[33][34] Goodblatt contends that while Bar Kokhba rendered much of the Judaean Mountains and the Hebron Hills desolate, Jewish communities continued to thrive in other parts of Judea and Palestine as a whole.

Literary and archaeological evidence indicates that in the Late Roman-early Byzantine era Jewish commuinities thrived along the eastern, southern and western edges of Judah, in the Galilee, Golan and the Beit Shean region.

Apostates from Judaism (aside from converts to Christianity) received little notice in antiquity from either Jewish or non-Jewish writers, but ambitious individuals are known to have turned pagan before the war, and it stands to reason that many more did so after its disastrous conclusion.

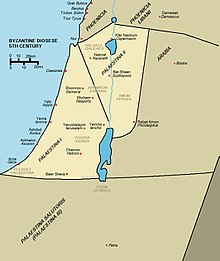

[46] During this period, Jews were concentrated in the Galilee, the Golan and marginal areas of the Judaean hills,[47] between Eleutheropolis and Hebron in the Daromas,[46] with significant Jewish settlement in the strip between Ein Gedi and Ascalon.

However, the main centres of Jewish life and culture during this period were the cosmopolitan cities of the coastal plains, particularly Lydda, Jamnia, Azotus and Caesarea Maritima.

[43] However, Christianity's early influence in either the Jewish, Samaritan or pagan rural areas was minor and came at a much later stage around the sixth century, when many of the community churches in Judea, western Galilee, the Naqab and other places were built.

By counting settlements, Avi-Yonah estimated that Jews comprised half the population of the Galilee at the end of the 3rd century, and a quarter in the other parts of the country, but had declined to 10–15% of the total by 614.

[73] According to archaeologist Gideon Avni, archaeological surveys show that most Christian settlements and sites preserved their identity up to the crusader period, supplemented by the numerosity of churches and monasteries all over Palestine.

[73] The early Muslim population, on the other hand, was confined to the Umayyad palaces in the Jordan Valley and around the Sea of Galilee, the ribat fortresses along the coast and the farms of the Naqab desert.

[75] Michael Ehrlich argues that the decline in urban centers likely caused local ecclesiastical administrations to weaken or disappear altogether, leaving Christians most susceptible to conversion.

[71] Per Ellenblum, the eastern Galilee and central Samaria, where Jews and Samaritans were concentrated respectively, were converted rather quickly and had a Muslim or Jewish-Muslim majority by the crusader period.

[76] The introduction of Islam in the Hebron hills is archaeologically attested in Jewish villages but not Christian ones, mainly in Susya and Eshtemoa, where the local synagogues were repurposed as mosques.

[71] On the other hand, Sufis played an important role in the Islamization of the hinterland of Jerusalem, where they built many religious buildings during the Mamluk period, transforming the cultural landscape.

These migrants primarily settled in the low country: in the Beisan area, Wadi Araba, the Jezreel valley, the Shephelah, the coastal plain and the Negev desert.

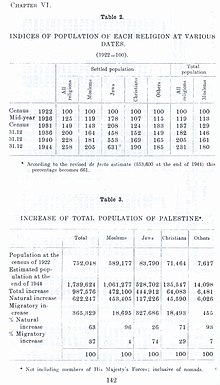

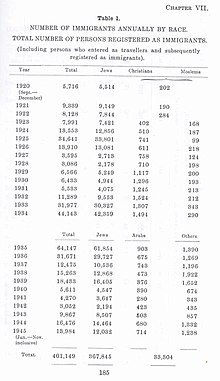

[102] Qafisheh calculated this using population and immigration statistics from the 1946 Survey of Palestine, as well as the fact that 37,997 people acquired provisional Palestinian naturalization certificates in September 1922 for the purpose of voting in the legislative election,[103] of which all but 100 were Jews.

[114] According to Roberto Bachi, head of the Israeli Institute of Statistics from 1949 onwards, between 1922 and 1945 there was a net Arab migration into Palestine of between 40,000 and 42,000, excluding 9,700 people who were incorporated after territorial adjustments were made to the borders in the 1920s.

Although the reasons for growth were exogenous to Palestine the bearers were not waves of Jewish immigration, foreign intervention nor Ottoman reforms but "primarily local Arab Muslims and Christians.

"[134] However, Gilbar did attribute the rapid growth of Jaffa and Haifa in the final three decades of Ottoman rule in part to migration, writing that "both attracted population from the rural and urban surroundings and immigrants from outside Palestine.

He writes: As all the research by historian Fares Abdul Rahim and geographers of modern Palestine shows, the Arab population began to grow again in the middle of the nineteenth century.

[138] Among Jews, 68% were Sabras (Israeli-born), mostly second- or third-generation Israelis, and the rest are olim – 22% from Europe and the Americas, and 10% from Asia and Africa, including the Arab countries.

[137][failed verification] According to Sergio DellaPergola, if foreign workers and non-Jewish Russian immigrants in Israel are subtracted, Jews are already a minority in the land between the river and the sea.