Demographics of Japan

In 2023, the median age of Japanese people was projected to be 49.5 years, the highest level since 1950, compared to 29.5 for India, 38.8 for the United States and 39.8 for China.

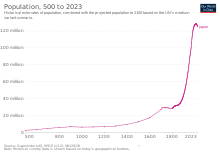

With a falling birth rate and a large share of its inhabitants reaching old age, Japan's total population is expected to continue declining, a trend that has been seen since 2010.

[4] Since 2010, Japan has experienced net population loss due to falling birth rates and minimal immigration, despite having one of the highest life expectancies in the world, at 85.00 years as of 2016[update] (it stood at 81.25 as of 2006).

However, the long-lasting effects of Japanese economic crisis during the Great Recession strongly slowed down immigration rates in Japan in 2010s.

[10] In 1991, as the bubble economy started to collapse, land prices began a steep decline, and within a few years fell 60% below their peak.

[21] After a decade of declining land prices, residents began moving back into central city areas (especially Tokyo's 23 wards), as evidenced by 2005 census figures.

Nevertheless, major cities, especially Tokyo, Yokohama and Fukuoka, and to a lesser extent Kyoto, Osaka and Nagoya, remain attractive to young people seeking education and jobs.

Japan faces the same problems that confront urban industrialized societies throughout the world: overcrowded cities and congested highways.

[33] The demographic shift in Japan's age profile has triggered concerns about the nation's economic future and the viability of its welfare state.

[46] In January 2023, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida pledged to take urgent steps to tackle the country's declining birth rate, calling it "now or never" for Japan's aging society; he had planned to double the budget for child-related policies by June 2023 and to set up a new government agency in April.

These descendants of premodern outcast hereditary occupational groups, such as butchers, leatherworkers, funeral directors, and certain entertainers, may be considered a Japanese analog of India's Dalits.

Historically, discrimination against these occupational groups was based on Buddhist prohibitions on killing and Shinto notions of pollution, and it was also a feature of governmental attempts to maintain social control.

[10] During the Edo period, such people were required to live in special buraku and, like the rest of the population, they were bound by sumptuary laws which were based on the inheritance of social class.

[10] The buraku continued to be treated as social outcasts and some casual interactions with the majority caste were perceived taboo until the era after World War II.

Checks on the backgrounds of families which were designed to ferret out buraku were commonly performed as a condition of marriage arrangements and employment applications,[10] but in Osaka, they have been illegal since 1985.

Historically, the Ainu were an indigenous hunting and gathering population who occupied most of northern Honshū as late as the Nara period (A.D. 710–94).

[58] Characterized as remnants of a primitive circumpolar culture, the fewer than 20,000 Ainu in 1990 were considered racially distinct and thus not fully Japanese.

Disease and a low birth rate had severely diminished their numbers over the past two centuries, and intermarriage had brought about an almost completely mixed population.

[59] Most intermarriages in Japan are between Japanese men and women from other Asian countries, including China, the Philippines and South Korea.

[60] Southeast Asia too, also has significant populations of people with half-Japanese ancestry, particularly in the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand.

[10][70] Government statistics show that in the 1980s significant numbers of people left the largest central cities (Tokyo and Osaka) to move to suburbs within their metropolitan areas.

As the government and private corporations have stressed internationalization, greater numbers of individuals have been directly affected, decreasing Japan's historical insularity.

By the late 1980s, these problems, particularly the bullying of returnee children in schools, had become a major public issue both in Japan and in Japanese communities abroad.

[citation needed] Reforms which took effect in 2015 relax visa requirements for "Highly Skilled Foreign Professionals" and create a new type of residence status with an unlimited period of stay.

[citation needed] According to the Civil Affairs Bureau of Japan's Ministry of Justice, the number of naturalized individuals peaked in 2003 at 17,633, before declining to 8,800 by 2023.

[87] Most foreign residents in Japan come from Brazil or from other Asian countries, particularly from China, Vietnam, South Korea, the Philippines, and Nepal.

Within this group, a number hold Special Permanent Resident status, granted under the terms of the Normalisation Treaty (22nd June 1965) between South Korea and Japan.

[87] In the following year the government contrived, with the help of the Red Cross, a scheme to "repatriate" Korean residents, who mainly were from the Southern Provinces, to their "home" of North Korea.

Vietnamese made the largest proportion of these new foreign residents, whilst Nepalese, Filipino, Chinese and Taiwanese are also significant in numbers.

However, the majority of these immigrants will only remain in Japan for a maximum of five years, as many of them have entered the country in order to complete trainee programmes.

KANTO , KEIHANSHIN and TOKAI are three largest metropolitan areas which have about 2/3 of total population of Japan. Out of 47 prefectures, 13 are red and 34 are green.

The population of Japan has been decreasing since 2011. Only 8 prefectures had increased its population compared to 2010, due to internal migration to large cities.