Desargues's theorem

Commonly, to remove these exceptions, mathematicians "complete" the Euclidean plane by adding points at infinity, following Jean-Victor Poncelet.

In an affine space such as the Euclidean plane a similar statement is true, but only if one lists various exceptions involving parallel lines.

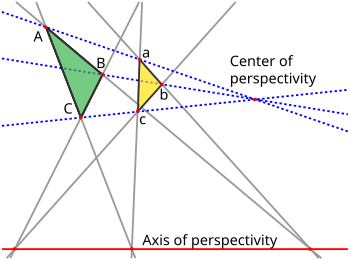

Under the standard duality of plane projective geometry (where points correspond to lines and collinearity of points corresponds to concurrency of lines), the statement of Desargues's theorem is self-dual: axial perspectivity is translated into central perspectivity and vice versa.

Historically, the theorem only read, "In a projective space, a pair of centrally perspective triangles is axially perspective" and the dual of this statement was called the converse of Desargues's theorem and was always referred to by that name.

Desargues's theorem can be stated as follows: The points A, B, a and b are coplanar (lie in the same plane) because of the assumed concurrency of Aa and Bb.

The last step of the proof fails if the projective space has dimension less than 3, as in this case it is not possible to find a point not in the plane.

As there are non-Desarguesian projective planes in which Desargues's theorem is not true,[5] some extra conditions need to be met in order to prove it.

These conditions usually take the form of assuming the existence of sufficiently many collineations of a certain type, which in turn leads to showing that the underlying algebraic coordinate system must be a division ring (skewfield).

Satisfying Pappus's theorem universally is equivalent to having the underlying coordinate system be commutative.