Resolution of singularities

The condition that the map is proper is needed to exclude trivial solutions, such as taking X′ to be the subvariety of non-singular points of X.

More generally, it is often useful to resolve the singularities of a variety X embedded into a larger variety W. Suppose we have a closed embedding of X into a regular variety W. A strong desingularization of X is given by a proper birational morphism from a regular variety W′ to W subject to some of the following conditions (the exact choice of conditions depends on the author): Hironaka showed that there is a strong desingularization satisfying the first three conditions above whenever X is defined over a field of characteristic 0, and his construction was improved by several authors (see below) so that it satisfies all conditions above.

In higher dimensions this is no longer true: varieties can have many different nonsingular projective models.

Normalization removes all singularities in codimension 1, so it works for curves but not in higher dimensions.

There were several attempts to prove resolution for surfaces over the complex numbers by Del Pezzo (1892), Levi (1899), Severi (1914), Chisini (1921), and Albanese (1924), but Zariski (1935, chapter I section 6) points out that none of these early attempts are complete, and all are vague (or even wrong) at some critical point of the argument.

Resolution of singularities has also been shown for all excellent 2-dimensional schemes (including all arithmetic surfaces) by Lipman (1978).

In general the analogue of Albanese's method for curves shows that for any variety one can reduce to singularities of order at most n!, where n is the dimension.

He first proved a theorem about local uniformization of valuation rings, valid for varieties of any dimension over any field of characteristic 0.

Cossart and Piltant (2008, 2009) proved resolution of singularities of 3-folds in all characteristics, by proving local uniformization in dimension at most 3, and then checking that Zariski's proof that this implies resolution for 3-folds still works in the positive characteristic case.

He proved that it was possible to resolve singularities of varieties over fields of characteristic 0 by repeatedly blowing up along non-singular subvarieties, using a very complicated argument by induction on the dimension.

de Jong (1996) found a different approach to resolution of singularities, generalizing Jung's method for surfaces, which was used by Bogomolov & Pantev (1996) and by Abramovich & de Jong (1997) to prove resolution of singularities in characteristic 0.

De Jong's method gave a weaker result for varieties of all dimensions in characteristic p, which is strong enough to act as a substitute for resolution for many purposes.

Grothendieck also suggested that the converse might hold: in other words, if a locally Noetherian scheme X is reduced and quasi excellent, then it is possible to resolve its singularities.

When X is defined over a field of characteristic 0 and is Noetherian, this follows from Hironaka's theorem, and when X has dimension at most 2 it was proved by Lipman.

Hauser (2010) gave a survey of work on the unsolved characteristic p resolution problem.

The lingering perception that the proof of resolution is very hard gradually diverged from reality.

The definition of this is made such that making this choice is meaningful, giving smooth centers transversal to the exceptional divisors.

The induction breaks in two steps: Here we say that a marked ideal is of maximal order if at some point of its co-support the order of the ideal is equal to d. A key ingredient in the strong resolution is the use of the Hilbert–Samuel function of the local rings of the points in the variety.

When the strict transform is a divisor (i.e., can be embedded as a codimension one subvariety in a smooth variety) it is known that there exists a strong resolution avoiding simple normal crossing points.

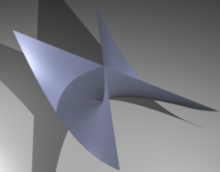

A natural way to resolve singularities is to repeatedly blow up some canonically chosen smooth subvariety.

However the whole singular set cannot be used since it is not smooth, and choosing one of the two axes breaks the symmetry between them so is not canonical.

The solution to this problem is that although blowing up the origin does not change the type of the singularity, it does give a subtle improvement: it breaks the symmetry between the two singular axes because one of them is an exceptional divisor for a previous blowup, so it is now permissible to blow up just one of these.

However, in order to exploit this the resolution procedure needs to treat these 2 singularities differently, even though they are locally the same.

The Atiyah flop gives an example in 3 dimensions of a singularity with no minimal resolution.

If f:A→B is the blowup of the origin of a quadric cone B in affine 3-space, then f×f:A×A→B×B cannot be produced by an étale local resolution procedure, essentially because the exceptional locus has 2 components that intersect.

Construction of a desingularization of a variety X may not produce centers of blowings up that are smooth subvarieties of X.

[3] Therefore, the resulting desingularization, when restricted to the abstract variety X, is not obtained by blowing up regular subvarieties of X.

To produce centers of blowings up that are regular subvarieties of X stronger proofs use the Hilbert-Samuel function of the local rings of X rather than the order of its ideal in the local embedding in W.[4] After the resolution the total transform, the union of the strict transform, X, and the exceptional divisor, is a variety that can be made, at best, to have simple normal crossing singularities.

The problem is to find a resolution that is an isomorphism over the set of smooth and simple normal crossing points.

When X is a divisor, i.e. it can be embedded as a codimension-one subvariety in a smooth variety it is known to be true the existence of the strong resolution avoiding simple normal crossing points.