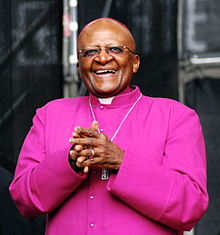

Desmond Tutu

Although warning the National Party government that anger at apartheid would lead to racial violence, as an activist he stressed non-violent protest and foreign economic pressure to bring about universal suffrage.

After President F. W. de Klerk released the anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela from prison in 1990 and the pair led negotiations to end apartheid and introduce multi-racial democracy, Tutu assisted as a mediator between rival black factions.

After the 1994 general election resulted in a coalition government headed by Mandela, the latter selected Tutu to chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate past human rights abuses committed by both pro and anti-apartheid groups.

[52] At the college, Tutu studied the Bible, Anglican doctrine, church history, and Christian ethics,[53] earning a Licentiate of Theology degree,[54] and winning the archbishop's annual essay prize.

[63] Many in South Africa's white-dominated Anglican establishment felt the need for more black Africans in positions of ecclesiastical authority; to assist in this, Aelfred Stubbs proposed that Tutu train as a theology teacher at King's College London (KCL).

[71] The family moved into the curate's flat behind the Church of St Alban the Martyr in Golders Green, where Tutu assisted Sunday services, the first time that he had ministered to a white congregation.

[116] Moving to the city, Tutu lived not in the official dean's residence in the white suburb of Houghton but rather in a house on a middle-class street in the Orlando West township of Soweto, a largely impoverished black area.

[148] Hegr also developed a new style of leadership, appointing senior staff who were capable of taking the initiative, delegating much of the SACC's detailed work to them, and keeping in touch with them through meetings and memorandums.

[175] Tutu gained a popular following in the US, where he was often compared to civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., although white conservatives like Pat Buchanan and Jerry Falwell lambasted him as an alleged communist sympathiser.

[213] In July 1985, Botha declared a state of emergency in 36 magisterial districts, suspending civil liberties and giving the security services additional powers;[214] he rebuffed Tutu's offer to serve as a go-between for the government and leading black organisations.

[240] Along with Boesak and Stephen Naidoo, Tutu mediated conflicts between black protesters and the security forces; they for instance worked to avoid clashes at the 1987 funeral of ANC guerrilla Ashley Kriel.

[254] To mark the sixth anniversary of the UDF's foundation he held a "service of witness" at the cathedral,[255] and in September organised a church memorial for those protesters who had been killed in clashes with the security forces.

At the Lambeth Conference of 1988, he backed a resolution condemning the use of violence by all sides; Tutu believed that Irish republicans had not exhausted peaceful means of bringing about change and should not resort to armed struggle.

[316] More serious was Tutu's criticism of Mandela's retention of South Africa's apartheid-era armaments industry and the significant pay packet that newly elected members of parliament adopted.

[321] Tutu proposed that the TRC adopt a threefold approach: the first being confession, with those responsible for human rights abuses fully disclosing their activities, the second being forgiveness in the form of a legal amnesty from prosecution, and the third being restitution, with the perpetrators making amends to their victims.

[294] He became increasingly frustrated following the collapse of the 2000 Camp David Summit,[294] and in 2002 gave a widely publicised speech denouncing Israeli policy regarding the Palestinians and calling for sanctions against Israel.

"[294] Tutu was named to head a United Nations fact-finding mission to Beit Hanoun in the Gaza Strip to investigate the November 2006 incident in which soldiers from the Israel Defense Forces killed 19 civilians.

[294] It was there, in February, that he broke his normal rule on not joining protests outside South Africa by taking part in a New York City demonstration against plans for the United States to launch the Iraq War.

[353] In 2004, he gave the inaugural lecture at the Church of Christ the King, where he commended the achievements made in South Africa over the previous decade although warned of widening wealth disparity among its population.

[364] During the 2008 Tibetan unrest, Tutu marched in a pro-Tibet demonstration in San Francisco; there, he called on heads of states to boycott the 2008 Summer Olympics opening ceremony in Beijing "for the sake of the beautiful people of Tibet".

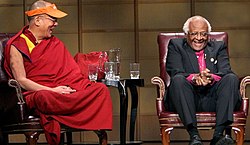

[365] Tutu invited the Tibetan Buddhist leader, the 14th Dalai Lama, to attend his 80th birthday in October 2011, although the South African government did not grant him entry; observers suggested that they had not given permission so as not to offend the People's Republic of China, a major trading partner.

[Tutu's] extrovert nature conceals a private, introvert side that needs space and regular periods of quiet; his jocularity runs alongside a deep seriousness; his occasional bursts of apparent arrogance mask a genuine humility before God and his fellow men.

He is a true son of Africa who can move easily in European and American circles, a man of the people who enjoys ritual and episcopal splendour, a member of an established Church, in some ways a traditionalist, who takes a radical, provocative and fearless stand against authority if he sees it to be unjust.

It is usually the most spiritual who can rejoice in all created things and Tutu has no problem in reconciling the sacred and the secular, but critics note a conflict between his socialist ideology and his desire to live comfortably, dress well and lead a life that, while unexceptional in Europe or America, is considered affluent, tainted with capitalism, in the eyes of the deprived black community of South Africa.

[399] Du Boulay noted that his "typical African warmth and a spontaneous lack of inhibition" proved shocking to many of the "reticent English" whom he encountered when in England,[400] but that it also meant that he had the "ability to endear himself to virtually everyone who actually meets him".

[407] Tutu has also been described as being sensitive,[413] and very easily hurt, an aspect of his personality which he concealed from the public eye;[407] Du Boulay noted that he "reacts to emotional pain" in an "almost childlike way".

He noted that whereas the latter was a quicker and more efficient way of exterminating whole populations, the National Party's policy of forcibly relocating black South Africans to areas where they lacked access to food and sanitation had much the same result.

[163] He and his wife boycotted a lecture given at the Federal Theological Institute by former British Prime Minister Alec Douglas-Home in the 1960s; Tutu noted that they did so because Britain's Conservative Party had "behaved abominably over issues which touched our hearts most nearly".

[457] He tried to avoid alignment with any particular political party; in the 1980s, for instance, he signed a plea urging anti-apartheid activists in the United States to support both the ANC and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC).

[337] Ultimately, Allen thought that perhaps Tutu's "greatest legacy" was the fact that he gave "to the world as it entered the twenty-first century an African model for expressing the nature of human community".