Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems

[2] The book was dedicated to Galileo's patron, Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, who received the first printed copy on February 22, 1632.

The name by which the work is now known was extracted by the printer from the description on the title page when permission was given to reprint it with an approved preface by a Catholic theologian in 1744.

Although the book is presented formally as a consideration of both systems (as it needed to be in order to be published at all), there is no question that the Copernican side gets the better of the argument.

Some of this is to show what Galileo considered good science, such as the discussion of William Gilbert's work on magnetism.

This is a classic exposition of the inertial frame of reference and refutes the objection that if we were moving hundreds of kilometres an hour as the Earth rotated, anything that one dropped would rapidly fall behind and drift to the west.

Galileo attempted a fourth class of argument: As an account of the causation of tides or a proof of the Earth's motion, it is a failure.

"[12] On the other hand, Einstein used a rather different description: It was Galileo's longing for a mechanical proof of the motion of the earth which misled him into formulating a wrong theory of the tides.

Galileo fails to discuss the possibility of non-circular orbits, although Johannes Kepler had sent him a copy of his 1609 book, Astronomia nova, in which he proposes elliptical orbits—correctly calculating that of Mars.

Four and a half decades after Galileo's death, Isaac Newton published his laws of motion and gravity, from which a heliocentric system with planets in approximately elliptical orbits is deducible.

"Preface: To the Discerning Reader" refers to the ban on the "Pythagorean opinion that the earth moves" and says that the author "takes the Copernican side with a pure mathematical hypothesis".

He suggests that the numbers were "trifles which later spread among the vulgar" and that their definitions, such as those of straight lines and right angles, were more useful in establishing the dimensions.

Simplicio's response was that Aristotle thought that in physical matters mathematical demonstration was not always needed.

Salviati attacks Aristotle's definition of the heavens as incorruptible and unchanging whilst only the lunar-bound zone shows change.

Simplicio argues that sunspots could simply be small opaque objects passing in front of the Sun, but Salviati points out that some appear or disappear randomly and those at the edge are flattened, unlike separate bodies.

Experiments with a mirror are used to show that the Moon's surface must be opaque and not a perfect crystal sphere as Simplicio believes.

Salviati points out that days on the Moon are a month long and despite the varied terrain that the telescope has disclosed, it would not sustain life.

Humans acquire mathematical truths slowly and hesitantly, whereas God knows the full infinity of them intuitively.

And when one looks into the marvellous things men have understood and contrived, then clearly the human mind is one of the most excellent of God's works.

There is one supreme motion—that by which the Sun, Moon, planets and fixed stars appear to be moved from east to west in the space of 24 hours.

He also points out that density of the material does not make much difference: a lead ball might only accelerate twice as fast as one of cork.

Simplicio now gives the greatest argument against the annual motion of the Earth that if it moves then it can no longer be the center of the zodiac, the world.

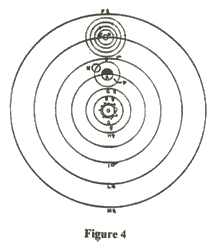

He encourages Simplicio to make a plan of the planets, starting with Venus and Mercury which are easily seen to rotate about the Sun.

Mars must also go about the Sun (as well as the Earth) since it is never seen horned, unlike Venus now seen through the telescope; similarly with Jupiter and Saturn.

Simplicio produces another booklet in which theological arguments are mixed with astronomic, but Salviati refuses to address the issues from Scripture.

So he produces the argument that the fixed stars must be at an inconceivable distance with the smallest larger than the whole orbit of the Earth.

Salviati explains that this all comes from a misrepresentation of what Copernicus said, resulting in a huge over-calculation of the size of a sixth magnitude star.

Not even Tycho, with his accurate instruments, set himself to measure the size of any star except the Sun and Moon.

Salviati maintains that "it is brash for our feebleness to attempt to judge the reasons for God's actions, and to call everything in the universe vain and superfluous which does not serve us".

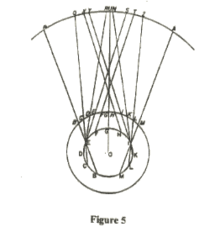

The primary effect only explains tides once a day; one must look elsewhere for the six-hour change, to the oscillation periods of the water.

It's impossible to make a full account of these things given the irregular nature of the sea basins.