Plato

[c] In modern times, Alfred North Whitehead said: "the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.

According to Diogenes Laërtius, writing hundreds of years after Plato's death, his birth name was Aristocles (Ἀριστοκλῆς), meaning 'best reputation'.

It was located in Athens, on a plot of land in the Grove of Hecademus or Academus,[33] named after an Attic hero in Greek mythology.

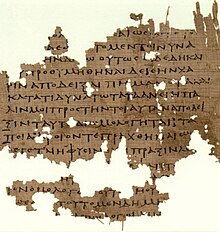

One story, based on a mutilated manuscript,[39] suggests Plato died in his bed, whilst a young Thracian girl played the flute to him.

The papyrus says that before death Plato "retained enough lucidity to critique the musician for her lack of rhythm", and that he was buried "in his designated garden in the Academy of Athens".

[54] Parmenides adopted an altogether contrary vision, arguing for the idea of a changeless, eternal universe and the view that change is an illusion.

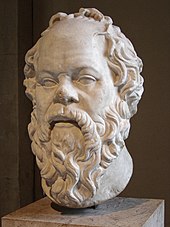

The theory of Forms is first introduced in the Phaedo dialogue (also known as On the Soul), wherein Socrates disputes the pluralism of Anaxagoras, then the most popular response to Heraclitus and Parmenides.

[59] He uses this idea of reincarnation to introduce the concept that knowledge is a matter of recollection of things acquainted with before one is born, and not of observation or study.

Many have interpreted Plato as stating – even having been the first to write – that knowledge is justified true belief, an influential view that informed future developments in epistemology.

[63][64] In the Sophist, Statesman, Republic, Timaeus, and the Parmenides, Plato associates knowledge with the apprehension of unchanging Forms and their relationships to one another (which he calls "expertise" in dialectic), including through the processes of collection and division.

[67] Several dialogues discuss ethics including virtue and vice, pleasure and pain, crime and punishment, and justice and medicine.

He speaks approvingly of this, and other forms of divine madness (drunkenness, eroticism, and dreaming) in the Phaedrus,[71] and yet in the Republic wants to outlaw Homer's great poetry, and laughter as well.

[76] He considered that only a few people were capable or interested in following a reasoned philosophical discourse, but men in general are attracted by stories and tales.

Diogenes the Cynic took issue with the former definition, reportedly producing a recently plucked chicken with the exclamation of "Here is Plato’s man!

[81] Simon Blackburn adopts the first, saying that Plato's dialectic is "the process of eliciting the truth by means of questions aimed at opening out what is already implicitly known, or at exposing the contradictions and muddles of an opponent's position.

"[81] Karl Popper, on the other hand, claims that dialectic is the art of intuition for "visualising the divine originals, the Forms or Ideas, of unveiling the Great Mystery behind the common man's everyday world of appearances".

[82] Other researchers also emphasise that Plato's philosophy has a strong religious component, e. g. in that philosophising is seen as a means of ascending to a higher level of consciousness.

[85] The 1578 edition[86] of Plato's complete works published by Henricus Stephanus (Henri Estienne) in Geneva also included parallel Latin translation and running commentary by Joannes Serranus (Jean de Serres).

[90][91] Thirty-five dialogues and thirteen letters (the Epistles) have traditionally been ascribed to Plato, though modern scholarship doubts the authenticity of at least some of these.

The works taken as genuine in antiquity but are now doubted by at least some modern scholars are: Alcibiades I (*),[h] Alcibiades II (‡), Clitophon (*), Epinomis (‡), Letters (*), Hipparchus (‡), Menexenus (*), Minos (‡), Lovers (‡), Theages (‡) The following works were transmitted under Plato's name in antiquity, but were already considered spurious by the 1st century AD: Axiochus, Definitions, Demodocus, Epigrams, Eryxias, Halcyon, On Justice, On Virtue, Sisyphus.

The works are usually grouped into Early, Middle, and Late period; The following represents one relatively common division amongst developmentalist scholars.

The first witness who mentions its existence is Aristotle, who in his Physics writes: "It is true, indeed, that the account he gives there [i.e. in Timaeus] of the participant is different from what he says in his so-called unwritten teachings (Ancient Greek: ἄγραφα δόγματα, romanized: agrapha dogmata).

A modern scholar who recognized the importance of the unwritten doctrine of Plato was Heinrich Gomperz who described it in his speech during the 7th International Congress of Philosophy in 1930.

[107] Neoplatonism, a philosophical current that permeated Islamic scholarship, accentuated one facet of the Qur’anic conception of God—the transcendent—while seemingly neglecting another—the creative.

This philosophical tradition, introduced by Al-Farabi and subsequently elaborated upon by figures such as Avicenna, postulated that all phenomena emanated from the divine source.

[108] Inspired by Plato's Republic, Al-Farabi extended his inquiry beyond mere political theory, proposing an ideal city governed by philosopher-kings.

[111] During the Renaissance, George Gemistos Plethon brought Plato's original writings to Florence from Constantinople in the century of its fall.

Many of the greatest early modern scientists and artists who broke with Scholasticism, with the support of the Plato-inspired Lorenzo (grandson of Cosimo), saw Plato's philosophy as the basis for progress in the arts and sciences.

Karl Popper argued in the first volume of The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945) that Plato's proposal for a "utopian" political regime in the Republic was prototypically totalitarian; this has been disputed.

That the modern theory of justified true belief as knowledge, which Gettier addresses, is equivalent to Plato's is, however, accepted only by some scholars but rejected by others.