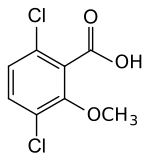

Dicamba

[5] It has been described as a "widely used, low-cost, environmentally friendly herbicide that does not persist in soils and shows little or no toxicity to wildlife and humans.

[2] Dicamba is a synthetic auxin that functions by increasing plant growth rate, leading to senescence and cell death.

In October 2016, the EPA launched a criminal investigation into the illegal application of older, drift prone formulations of dicamba onto these new plants.

[15][16] A less volatile formulation of dicamba made by Monsanto, designed to be less prone to vaporizing and inhibit unintended drift between fields, was approved for use in the United States by the EPA in 2016, and was commercially available in 2017.

[19][20] In 2011, the European Food Safety Authority identified dicamba's potential for long-range transport through the atmosphere as a critical area of concern.

[21] In 2022, the United States Environmental Protection Agency identified spray drift as the primary ecological risk for dicamba due to its potential effects on non-target terrestrial plants.

In 2022 the EPA identified potential occupational risks to handlers mixing and loading dry flowable formulations for application to sod and field crops.

[22] The Cross-Canada Study of Pesticides and Health found that exposure to dicamba increased the risk of non-Hodgkins lymphoma in men.

[25] The 2022 EPA draft ecological risk assessment identified potential adverse effects to birds, and bee larvae for all dicamba uses.

[8] The soil bacterium Pseudomonas maltophilia (strain DI-6) converts dicamba to 3,6-dichlorosalicylic acid (3,6-DCSA), which lacks herbicidal activity.

[6] In the 2000s, Monsanto incorporated one component of the three enzymes into the genome of soybean, cotton, and other broadleaf crop plants, making them resistant to dicamba.

[8] In 2017 and again in 2018, EPA amended the registrations of all OTT dicamba products following reports that farmers had experienced crop damage and economic losses resulting from spray drifting.

[8] Arkansas and Missouri banned the sale and use of dicamba in July 2017 in response to complaints of crop damage due to drift.

[8] In February 2018, it was reported that numerous farmers from 21 states had filed lawsuits against Monsanto alleging that dicamba damaged their crops, with the most prominent cases coming from Missouri and Arkansas.

[47][48] The lawsuit involves a peach farmer who alleged that dicamba-based herbicides caused significant damage to his crops and trees.

[55][56] Court documents revealed Monsanto had used dicamba drift as a sales pitch to convince farmers to buy their proprietary dicamba-resistant seeds or face devastated crops.

[60] On 25 November 2020, U.S. District Judge Stephen Limbaugh Jr. reduced the punitive damage amount in the Bader Farms case to $60 million.