Dick Turpin

He is also known for a fictional 200-mile (320 km) overnight ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess, a story that was made famous by the Victorian novelist William Harrison Ainsworth almost 100 years after Turpin's death.

[11] By October 1734 several in the gang had either been captured or had fled,[12] and the remaining members moved away from poaching, raiding the home of a chandler and grocer named Peter Split, at Woodford.

[nb 3] Two nights later they struck again, at the Woodford home of a gentleman named Richard Woolridge, a Furnisher of Small Arms in the Office of Ordnance at the Tower of London.

They afterwards went into the cellar and drank several bottles of ale and wine, and broiled some meat, ate the relicts of a fillet of veal &c. While they were doing this, two of their gang went to Mr Turkles, a farmer's, who rents one end of the widow's house, and robbed him of above £20 and then they all went off, taking two of the farmer's horses, to carry off their luggage, the horses were found on Sunday the following morning in Old Street, and stayed about three hours in the house.The gang lived in or around London.

[26] On 15 February 1735, while Wheeler was busy confessing to the authorities, "three or four men" (most likely Samuel Gregory, Herbert Haines, Turpin, and possibly Thomas Rowden) robbed the house of a Mrs St. John at Chingford.

[29] Six days after the arrest of Fielder, Saunders, and Wheeler – just as Turpin and his associates were returning from Gravesend – Rose, Brazier, and Walker were captured at a chandler's shop in Westminster, while drinking punch.

[32][33] Walker died while still in Newgate Prison, but the remaining three were hanged at Tyburn gallows on 10 March, before their bodies were hung to rot in gibbets on Edgware Road.

His brothers were arrested on 9 April[37] in Rake, West Sussex, after a struggle during which Samuel lost the tip of his nose to a sword, and Jeremy was shot in the leg.

Although he may have been involved in earlier highway robberies on 10 and 12 April,[37] he was first identified as a suspect in one event on 10 July, as "Turpin the butcher", along with Thomas Rowden, "the pewterer".

The trio were responsible for a string of robberies between March and April 1737,[48] which ended suddenly in an incident at Whitechapel, after King (or Turpin, depending upon which report is read) had stolen a horse near Waltham Forest.

[54] The shooting was reported in The Gentleman's Magazine: It having been represented to the King, that Richard Turpin did on Wednesday the 4th of May last, barbarously murder Thomas Morris, Servant to Henry Tomson, one of the Keepers of Epping-Forest, and commit other notorious Felonies and Robberies near London, his Majesty is pleased to promise his most gracious Pardon to any of his Accomplices, and a Reward of 200l.

Travelling across the River Humber between the historic counties of the East Riding of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, he posed as a horse trader, and often hunted alongside local gentlemen.

Three East Riding justices (JPs), George Crowle (Member of Parliament for Hull), Hugh Bethell, and Marmaduke Constable, travelled to Brough and took written depositions about the incident.

When contacted, the JP at Long Sutton (a Mr Delamere) confirmed that John Palmer had lived there for about nine months,[60] but that he was suspected of stealing sheep, and had escaped the custody of the local constable.

[63] Robbery combined with violence was "the sort of offence, second only to premeditated murder (a relatively uncommon crime), most likely to be prosecuted and punished to [the law's] utmost rigour".

About a month after "Palmer" had been moved to York Castle,[60] Thomas Creasy, the owner of the three horses stolen by Turpin, managed to track them down and recover them, and it was for these thefts that he was eventually tried.

The letter was then moved to the post office at Saffron Walden where James Smith, who had taught his younger schoolmate Turpin how to write while they were at school, recognised the handwriting.

Turpin had no defence barrister; during this period of English history, for those accused of felonies it was costly to find legal representation,[73] their interests were cared for by the presiding judge.

On 7 April 1739, followed by his mourners, Turpin and John Stead (a horse thief) were taken through York by open cart to Knavesmire, which was then the city's equivalent of London's Tyburn gallows.

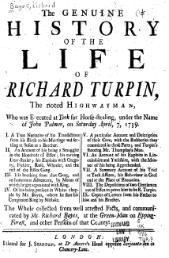

[86] The speeches of the condemned, biographies of criminals, and trial literature, were popular genres during the late 17th and early 18th centuries; written for a mass audience and a precursor to the modern novel, they were "produced on a scale which beggars comparison with any period before or since".

[87] Such literature functioned as news and a "forum in which anxieties about crime, punishment, sin, salvation, the workings of providence and social and moral transgression generally could be expressed and negotiated.

[86] His account of those present during the robberies committed by the Essex Gang often contains names that never appeared in contemporary newspaper reports, suggesting, according to author Derek Barlow, that Bayes embellished his story.

Turpin may have known Matthew King as early as 1734,[nb 11] and had an active association with him from February 1737, but the story of the "Gentleman Highwayman" may have been created only to link the end of the Essex gang with the author's own recollection of events.

[90] Barlow also views the account of the theft of Turpin's corpse, appended to Thomas Kyll's publication of 1739, as "handled with such delicacy as to amount almost to reverence", and therefore of suspect provenance.

It was, however, the story of a fabled ride from London to York that provided the impetus for 19th-century author William Harrison Ainsworth to include and embellish the exploit in his 1834 novel Rookwood.

Like our great Nelson, he knew fear only by name; and when he thus trusted himself in the hands of strangers, confident in himself and in his own resources, he felt perfectly easy as to the result [...] Turpin was the ultimus Romanorum, the last of a race, which—we were almost about to say we regret—is now altogether extinct.

With him expired the chivalrous spirit which animated successively the bosoms of so many knights of the road; with him died away that passionate love of enterprise, that high spirit of devotion to the fair sex, which was first breathed upon the highway by the gay, gallant Claude Du-Val, the Bayard of the road—Le filou sans peur et sans reproche—but which was extinguished at last by the cord that tied the heroic Turpin to the remorseless tree.

Ainsworth's tale of Turpin's overnight journey from London to York on his mare Black Bess has its origins in an episode recorded by Daniel Defoe, in his 1727 work A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain.

After committing a robbery in Kent in 1676, William Nevison apparently rode to York to establish an alibi, and Defoe's account of that journey became part of folk legend.

These narratives, which transformed Turpin from a pockmarked thug and murderer into "a gentleman of the road [and] a protector of the weak", followed a popular cultural tradition of romanticising English criminals.