Didache

'Teaching'),[1] also known as The Lord's Teaching Through the Twelve Apostles to the Nations (Διδαχὴ Κυρίου διὰ τῶν δώδεκα ἀποστόλων τοῖς ἔθνεσιν, Didachḕ Kyríou dià tō̂n dṓdeka apostólōn toîs éthnesin), is a brief anonymous early Christian treatise (ancient church order) written in Koine Greek, dated by modern scholars to the first[2] or (less commonly) second century AD.

[a] The text, parts of which constitute the oldest extant written catechism, has three main sections dealing with Christian ethics, rituals such as baptism and Eucharist, and Church organization.

[5] The opening chapters, which also appear in other early Christian texts like the Epistle of Barnabas, are likely derived from an earlier Jewish source.

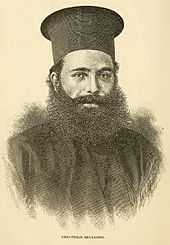

Lost for centuries, a Greek manuscript of the Didache was rediscovered in 1873 by Philotheos Bryennios, Metropolitan of Nicomedia, in the Codex Hierosolymitanus, a compilation of texts of the Apostolic Fathers found in the Jerusalem Monastery of the Most Holy Sepulchre in Constantinople.

[16] The teaching is an anonymous pastoral manual which Aaron Milavec states "reveals more about how Jewish-Christians saw themselves and how they adapted their Judaism for gentiles than any other book in the Christian Scriptures".

[2] The community that produced the Didache could have been based in Syria, as it addressed the gentiles but from a Judaic perspective, at some remove from Jerusalem, and shows no evidence of Pauline influence.

[20] The Didache is mentioned by Eusebius (c. 324) as the Teachings of the Apostles along with other books he considered non-canonical:[21] Let there be placed among the spurious works the Acts of Paul, the so-called Shepherd and the Apocalypse of Peter, and besides these the Epistle of Barnabas, and what are called the Teachings of the Apostles, and also the Apocalypse of John, if this be thought proper; for as I wrote before, some reject it, and others place it in the canon.Athanasius of Alexandria (367) and Tyrannius Rufinus (c. 380) list the Didache among apocrypha.

The Shepherd of Hermas seems to reflect it, and Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria,[c] and Origen also seem to use the work, and so in the West do Optatus and the "Gesta apud Zenophilum".

This is short for the header found on the document and the title used by the Church Fathers, "The Lord's Teaching of the Twelve Apostles".

[g] Willy Rordorf considered the first five chapters as "essentially Jewish, but the Christian community was able to use it" by adding the "evangelical section".

"[31] Apostolic Fathers (1992) notes: The Two Ways material appears to have been intended, in light of 7.1, as a summary of basic instruction about the Christian life to be taught to those who were preparing for baptism and church membership.

The interrelationships between these various documents, however, are quite complex and much remains to be worked out.The closest parallels in the use of the Two Ways doctrine are found among the Essene Jews at the Dead Sea Scrolls community.

The first chapter opens with the Shema ("you shall love God"), the Great Commandment ("your neighbor as yourself"), and the Golden Rule in the negative form.

Then come short extracts in common with the Sermon on the Mount, together with a curious passage on giving and receiving, which is also cited with variations in Shepherd of Hermas (Mand., ii, 4–6).

The Latin omits 1:3–6 and 2:1, and these sections have no parallel in Epistle of Barnabas; therefore, they may be a later addition, suggesting Hermas and the present text of the Didache may have used a common source, or one may have relied on the other.

Chapter 2 contains the commandments against murder, adultery, corrupting boys, sexual promiscuity, theft, magic, sorcery, abortion, infanticide, coveting, perjury, false testimony, speaking evil, holding grudges, being double-minded, not acting as one speaks, greed, avarice, hypocrisy, maliciousness, arrogance, plotting evil against neighbors, hate, narcissism and expansions on these generally, with references to the words of Jesus.

[8] Vice lists, which are common appearances in Paul's epistles, were relatively unusual within ancient Judaism of the Old Testament times.

[36] The way of death and the "grave sin", which are forbidden, is reminiscent of the various "vice lists" found in the Pauline Epistles, which warn against engaging in certain behaviours if one wants to enter the Kingdom of God.

Contrasting what Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 6:9–10, Galatians 5:19–21, and what was written in 1 Timothy 1:9–11[i] with Didache 2 displays a certain commonality with one another, almost with the same warnings and words, except for one line: "thou shalt not corrupt boys".

The New Testament is rich in metaphors for baptism but offers few details about the practice itself, not even whether the candidates professed their faith in a formula.

[40] The Two Ways section of the Didache is presumably the sort of ethical instruction that catechumens (students) received in preparation for baptism.

This doxology derives from 1 Chronicles 29:11–13; Bruce M. Metzger held that the early church added it to the Lord's Prayer, creating the current Matthew reading.

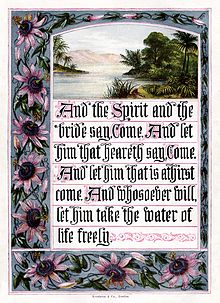

[43] The Didache includes two primitive and unusual prayers for the Eucharist ("thanksgiving"),[2] which is the central act of Christian worship.

[47] As with Paul's First Letter to the Corinthians, the Didache confirms that the Lord's supper was literally a meal, probably taking place in a "house church".

[52] The section beginning at 10.1 is a reworking of the Jewish birkat ha-mazon, a three-strophe prayer at the conclusion of a meal, which includes a blessing of God for sustaining the universe, a blessing of God who gives the gifts of food, earth, and covenant, and a prayer for the restoration of Jerusalem; the content is "Christianized", but the form remains Jewish.

[2] Itinerant apostles and prophets are of great importance, serving as "chief priests" and possibly celebrating the Eucharist.

[2] Christians are enjoined to gather on Sunday to break bread, but to confess their sins first as well as reconcile themselves with others if they have grievances (Chapter 14).

Significant similarities between the Didache and the Gospel of Matthew have been found[5] as these writings share words, phrases, and motifs.

One argument that suggests a common environment is that the community of both the Didache and the gospel of Matthew was probably composed of Jewish Christians from the beginning.