Karl Kraus (writer)

Beginning in April of the same year, he began contributing to the paper Wiener Literaturzeitung, starting with a critique of Gerhart Hauptmann's The Weavers.

In 1896, Kraus left university without a diploma to begin work as an actor, stage director and performer, joining the Young Vienna group, which included Peter Altenberg, Leopold Andrian, Hermann Bahr, Richard Beer-Hofmann, Arthur Schnitzler, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and Felix Salten.

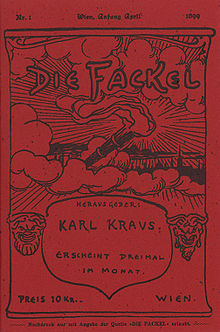

On 1 April 1899, Kraus renounced Judaism, and in the same year he founded his own magazine, Die Fackel (German: The Torch), which he continued to direct, publish, and write until his death, and from which he launched his attacks on hypocrisy, psychoanalysis, corruption of the Habsburg empire, nationalism of the pan-German movement, laissez-faire economic policies, and numerous other subjects.

In its first decade, contributors included such well-known writers and artists as Peter Altenberg, Richard Dehmel, Egon Friedell, Oskar Kokoschka, Else Lasker-Schüler, Adolf Loos, Heinrich Mann, Arnold Schoenberg, August Strindberg, Georg Trakl, Frank Wedekind, Franz Werfel, Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Oscar Wilde.

Notable enemies were Maximilian Harden (in the mud of the Harden–Eulenburg affair), Moriz Benedikt (owner of the newspaper Neue Freie Presse), Alfred Kerr, Hermann Bahr, Imre Bekessy [de] and Johann Schober.

In 1902, Kraus published Sittlichkeit und Kriminalität (Morality and Criminal Justice), for the first time commenting on what was to become one of his main preoccupations: he attacked the general opinion of the time that it was necessary to defend sexual morality by means of criminal justice (Der Skandal fängt an, wenn die Polizei ihm ein Ende macht, The Scandal Starts When the Police Ends It).

Elias Canetti, who regularly attended Kraus's lectures, titled the second volume of his autobiography "Die Fackel" im Ohr ("The Torch" in the Ear) in reference to the magazine and its author.

[6] These plays' frank depiction of sexuality and violence, including lesbianism and an encounter with Jack the Ripper,[7] pushed against the boundaries of what was considered acceptable on the stage at the time.

Wedekind's works are considered among the precursors of expressionism, but in 1914, when expressionist poets like Richard Dehmel began producing war propaganda, Kraus became a fierce critic of them.

One controversy arose with the text Die Orgie, which exposed how the newspaper Neue Freie Presse was blatantly supporting Austria's Liberal Party's election campaign; the text was conceived as a guerrilla prank and sent as a fake letter to the newspaper (Die Fackel would publish it later in 1911); the enraged editor, who fell for the trick, responded by suing Kraus for "disturbing the serious business of politicians and editors".

In the subsequent time, Kraus wrote against the World War, and censors repeatedly confiscated or obstructed editions of Die Fackel.

Kraus's masterpiece is generally considered to be the massive satirical play about the First World War, Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind), which combines dialogue from contemporary documents with apocalyptic fantasy and commentary by two characters called "the Grumbler" and "the Optimist".

[citation needed] During January 1924, Kraus started a fight against Imre Békessy, publisher of the tabloid Die Stunde (The Hour), accusing him of extorting money from restaurant owners by threatening them with bad reviews unless they paid him.

Békessy retaliated with a libel campaign against Kraus, who in turn launched an Erledigung with the catchphrase "Hinaus aus Wien mit dem Schuft!"

[15] Other commentators, such as Edward Timms, have argued that Kraus respected Freud, though with reservations about the application of some of his theories, and that his views were far less black-and-white than Szasz suggests.

Viennese composer Ernst Krenek described meeting the writer in 1932: "At a time when people were generally decrying the Japanese bombardment of Shanghai, I met Karl Kraus struggling over one of his famous comma problems.

"[19] The Austrian author Stefan Zweig once called Kraus "the master of venomous ridicule" (der Meister des giftigen Spotts).

[20] Up to 1930, Kraus directed his satirical writings to figures of the center and the left of the political spectrum, as he considered the flaws of the right too self-evident to be worthy of his comment.

[22] Gregor von Rezzori wrote of Kraus, "[His] life stands as an example of moral uprightness and courage which should be put before anyone who writes, in no matter what language...

I had the privilege of listening to his conversation and watching his face, lit up by the pale fire of his fanatic love for the miracle of the German language and by his holy hatred for those who used it badly.