Ancient Greek cuisine

[1]: 95(129c) The cuisine was founded on the "Mediterranean triad" of cereals, olives, and grapes,[2] which had many uses and great commercial value, but other ingredients were as important, if not more so, to the average diet: most notably legumes.

[6] Breakfast (ἀκρατισμός akratismós and ἀκράτισμα akratisma, acratisma[7]) consisted of barley bread dipped in wine (ἄκρατος ákratos), sometimes complemented by figs, dates or olives.

[8] They also ate a sort of pancake called τηγανίτης (tēganítēs)[9] or ταγηνίας (tagēnías),[10] all words deriving from τάγηνον (tágēnon), "frying pan".

The ancient Greek custom of placing terracotta miniatures of furniture in children's graves gives a good idea of its style and design.

[33] As with modern dinner parties, the host could simply invite friends or family; but two other forms of social dining were well documented in ancient Greece: the entertainment of the all-male symposium, and the obligatory, regimental syssitia.

[34] However, wine was consumed with the food, and the beverages were accompanied by snacks (τραγήματα tragēmata) such as chestnuts, beans, toasted wheat, or honey cakes, all intended to absorb alcohol and extend the drinking spree.

The syssitia (τὰ συσσίτια tà syssítia) were mandatory meals shared by social or religious groups for men and youths, especially in Crete and Sparta.

First she set for them a fair and well made table that had feet of cyanus; On it there was a vessel of bronze and an onion to give relish to the drink, with honey and cakes of barley meal.Cereals formed the staple diet.

Philoxenus of Cythera describes in detail some cakes that were eaten as part of an elaborate dinner using the traditional dithyrambic style used for sacred Dionysian hymns: "mixed with safflower, toasted, wheat-oat-white-chickpea-little thistle-little-sesame-honey-mouthful of everything, with a honey rim".

[40] Melitoutta (Ancient Greek: μελιτοῦττα), was a honeycake[42][43][44] and oinoutta (οἰνοῦττα) was a cake or porridge of barley mixed with wine, water, and oil.

[49] Wheat grains were softened by soaking, then either reduced into gruel, or ground into flour (ἀλείατα aleíata) and kneaded and formed into loaves (ἄρτος ártos) or flatbreads, either plain or mixed with cheese or honey.

In Peace, Aristophanes employs the expression ἐσθίειν κριθὰς μόνας, literally "to eat only barley", with a meaning equivalent to the English "diet of bread and water".

[3] Legumes were essential to the Greek diet, and were harvested in the Mediterranean region from prehistoric times: the earliest and most common being lentils - which have been found in archeological sites in Greece dating to the Upper Paleolithic period.

[67] Vegetables were eaten as soups, boiled or mashed (ἔτνος etnos), seasoned with olive oil, vinegar, herbs or γάρον gáron, a fish sauce similar to Vietnamese nước mắm.

In the 8th century BCE, Hesiod describes the ideal country feast in Works and Days: But at that time let me have a shady rock and Bibline wine, a clot of curds and milk of drained goats with the flesh of a heifer fed in the woods, that has never calved, and of firstling kids; then also let me drink bright wine…[78]Meat is much less prominent in texts of the 5th century BCE onwards than in the earliest poetry[citation needed], but this may be a matter of genre rather than real evidence of changes in farming and food customs.

And love a fragrant pig within the oven.Hippolochus (3rd Century BCE) describes a wedding banquet in Macedonia with "chickens and ducks, and ringdoves, too, and a goose, and an abundance of suchlike viands piled high... following which came a second platter of silver, on which again lay a huge loaf, and geese, hares, young goats, and curiously moulded cakes besides, pigeons, turtle-doves, partridges, and other fowl in plenty..." and "a roast pig — a big one, too — which lay on its back upon it; the belly, seen from above, disclosed that it was full of many bounties.

"Naturally Spartans are the bravest men in the world," joked a Sybarite, "anyone in his senses would rather die ten thousand times than take his share of such a sorry diet".

[86] Archaeological excavations at Kavousi Kastro, Lerna, and Kastanas have shown that dogs were sometimes consumed in Bronze Age Greece, in addition to the more commonly-consumed pigs, cattle, sheep, and goats.

[87] Herodotus describes a "large fish... of the sort called Antacaei, without any prickly bones, and good for pickling," probably beluga[88] found in Greek colonies along the Dnieper River.

Quail, moorhen, capon, mallards, pheasants, larks, pigeons and doves were all domesticated in classical times, and were even for sale in markets.

Additionally, thrush, blackbirds, chaffinch, lark, starling, jay, jackdaw, sparrow, siskin, blackcap, Rock partridge, grebe, plover, coot, wagtail, francolin, and even cranes were hunted, or trapped, and eaten, and sometimes available in markets.

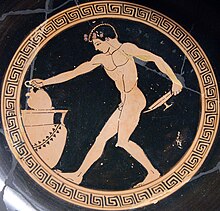

The ancient Greeks also used a vessel called a kylix (a shallow footed bowl), and for banquets the kantharos (a deep cup with handles) or the rhyton, a drinking horn often moulded into the form of a human or animal head.

Classicist John Wilkins notes that "in the Odyssey for example, good men are distinguished from bad and Greeks from foreigners partly in terms of how and what they ate.

The rural writer Hesiod, as cited above, spoke of his "flesh of a heifer fed in the woods, that has never calved, and of firstling kids" as being the perfect closing to a day.

[141] Culinary and gastronomical research was rejected as a sign of decadence: the inhabitants of the Persian Empire were considered so due to their luxurious taste, which manifested itself in their cuisine.

[142] The Greek authors took pleasure in describing the table of the Achaemenid Great King and his court: Herodotus,[143] Clearchus of Soli,[144] Strabo[145] and Ctesias[146] were unanimous in their descriptions.

[147] According to Polyaenus,[148] on discovering the dining hall of the Persian royal palace, Alexander the Great mocked their taste and blamed it for their defeat.

[149] In consequence of this cult of frugality, and the diminished regard for cuisine it inspired, the kitchen long remained the domain of women, free or enslaved.

They discussed the merits of various wines, vegetables, and meats, mentioning renowned dishes (stuffed cuttlefish, red tuna belly, prawns, lettuce watered with mead) and great cooks such as Soterides, chef to king Nicomedes I of Bithynia (who reigned from the 279 to 250 BCE).

In On the eating of flesh, Plutarch (1st–2nd century) elaborated on the barbarism of blood-spilling; inverting the usual terms of debate, he asked the meat-eater to justify his choice.