Differential geometry

It is intimately linked to the development of geometry more generally, of the notion of space and shape, and of topology, especially the study of manifolds.

Namely, as far back as Euclid's Elements it was understood that a straight line could be defined by its property of providing the shortest distance between two points, and applying this same principle to the surface of the Earth leads to the conclusion that great circles, which are only locally similar to straight lines in a flat plane, provide the shortest path between two points on the Earth's surface.

[1] This fact reflects the lack of a metric-preserving map of the Earth's surface onto a flat plane, a consequence of the later Theorema Egregium of Gauss.

At this time, the recent work of René Descartes introducing analytic coordinates to geometry allowed geometric shapes of increasing complexity to be described rigorously.

In particular around this time Pierre de Fermat, Newton, and Leibniz began the study of plane curves and the investigation of concepts such as points of inflection and circles of osculation, which aid in the measurement of curvature.

Shortly after this time the Bernoulli brothers, Jacob and Johann made important early contributions to the use of infinitesimals to study geometry.

In lectures by Johann Bernoulli at the time, later collated by L'Hopital into the first textbook on differential calculus, the tangents to plane curves of various types are computed using the condition

Thus Clairaut demonstrated an implicit understanding of the tangent space of a surface and studied this idea using calculus for the first time.

Around this same time, Leonhard Euler, originally a student of Johann Bernoulli, provided many significant contributions not just to the development of geometry, but to mathematics more broadly.

[3] In regards to differential geometry, Euler studied the notion of a geodesic on a surface deriving the first analytical geodesic equation, and later introduced the first set of intrinsic coordinate systems on a surface, beginning the theory of intrinsic geometry upon which modern geometric ideas are based.

[1] Around this time Euler's study of mechanics in the Mechanica lead to the realization that a mass traveling along a surface not under the effect of any force would traverse a geodesic path, an early precursor to the important foundational ideas of Einstein's general relativity, and also to the Euler–Lagrange equations and the first theory of the calculus of variations, which underpins in modern differential geometry many techniques in symplectic geometry and geometric analysis.

Several students of Monge made contributions to this same theory, and for example Charles Dupin provided a new interpretation of Euler's theorem in terms of the principle curvatures, which is the modern form of the equation.

[6] In his fundamental paper Gauss introduced the Gauss map, Gaussian curvature, first and second fundamental forms, proved the Theorema Egregium showing the intrinsic nature of the Gaussian curvature, and studied geodesics, computing the area of a geodesic triangle in various non-Euclidean geometries on surfaces.

At this time Riemann did not yet develop the modern notion of a manifold, as even the notion of a topological space had not been encountered, but he did propose that it might be possible to investigate or measure the properties of the metric of spacetime through the analysis of masses within spacetime, linking with the earlier observation of Euler that masses under the effect of no forces would travel along geodesics on surfaces, and predicting Einstein's fundamental observation of the equivalence principle a full 60 years before it appeared in the scientific literature.

[6][4] In the wake of Riemann's new description, the focus of techniques used to study differential geometry shifted from the ad hoc and extrinsic methods of the study of curves and surfaces to a more systematic approach in terms of tensor calculus and Klein's Erlangen program, and progress increased in the field.

[12] At the start of the 1900s there was a major movement within mathematics to formalise the foundational aspects of the subject to avoid crises of rigour and accuracy, known as Hilbert's program.

[13][4] Following this early development, many mathematicians contributed to the development of the modern theory, including Jean-Louis Koszul who introduced connections on vector bundles, Shiing-Shen Chern who introduced characteristic classes to the subject and began the study of complex manifolds, Sir William Vallance Douglas Hodge and Georges de Rham who expanded understanding of differential forms, Charles Ehresmann who introduced the theory of fibre bundles and Ehresmann connections, and others.

In the middle and late 20th century differential geometry as a subject expanded in scope and developed links to other areas of mathematics and physics.

During this same period primarily due to the influence of Michael Atiyah, new links between theoretical physics and differential geometry were formed.

Physicists such as Edward Witten, the only physicist to be awarded a Fields medal, made new impacts in mathematics by using topological quantum field theory and string theory to make predictions and provide frameworks for new rigorous mathematics, which has resulted for example in the conjectural mirror symmetry and the Seiberg–Witten invariants.

This is a concept of distance expressed by means of a smooth positive definite symmetric bilinear form defined on the tangent space at each point.

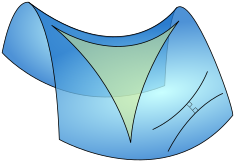

However, the Theorema Egregium of Carl Friedrich Gauss showed that for surfaces, the existence of a local isometry imposes that the Gaussian curvatures at the corresponding points must be the same.

In higher dimensions, the Riemann curvature tensor is an important pointwise invariant associated with a Riemannian manifold that measures how close it is to being flat.

A special case of this is a Lorentzian manifold, which is the mathematical basis of Einstein's general relativity theory of gravity.

Non-degenerate skew-symmetric bilinear forms can only exist on even-dimensional vector spaces, so symplectic manifolds necessarily have even dimension.

, which is unique up to multiplication by a nowhere vanishing function: A local 1-form on M is a contact form if the restriction of its exterior derivative to H is a non-degenerate two-form and thus induces a symplectic structure on Hp at each point.

Loosely speaking, this structure by itself is sufficient only for developing analysis on the manifold, while doing geometry requires, in addition, some way to relate the tangent spaces at different points, i.e. a notion of parallel transport.

More generally, differential geometers consider spaces with a vector bundle and an arbitrary affine connection which is not defined in terms of a metric.

Starting with the work of Riemann, the intrinsic point of view was developed, in which one cannot speak of moving "outside" the geometric object because it is considered to be given in a free-standing way.

In the formalism of geometric calculus both extrinsic and intrinsic geometry of a manifold can be characterized by a single bivector-valued one-form called the shape operator.