Diffusion of innovations

Rogers proposes that five main elements influence the spread of a new idea: the innovation itself, adopters, communication channels, time, and a social system.

The concept of diffusion was first studied by the French sociologist Gabriel Tarde in late 19th century[4] and by German and Austrian anthropologists and geographers such as Friedrich Ratzel and Leo Frobenius.

Agriculture technology was advancing rapidly, and researchers started to examine how independent farmers were adopting hybrid seeds, equipment, and techniques.

[5] A study of the adoption of hybrid corn seed in Iowa by Ryan and Gross (1943) solidified the prior work on diffusion into a distinct paradigm that would be cited consistently in the future.

[9] In organizational studies, its basic epidemiological or internal-influence form was formulated by H. Earl Pemberton,[10][11] such as postage stamps and standardized school ethics codes.

In 1962, Everett Rogers, a professor of rural sociology at Ohio State University, published his seminal work: Diffusion of Innovations.

Rogers applied it to the healthcare setting to address issues with hygiene, cancer prevention, family planning, and drunk driving.

For example, an innovation might be extremely complex, reducing its likelihood to be adopted and diffused, but it might be very compatible with a large advantage relative to current tools.

Innovations that match the organization's pre-existing system require fewer coincidental changes and are easy to assess and more likely to be adopted.

However, research suggested that simple behavioral models can still be used as a good predictor of organizational technology adoption when proper initial screening procedures are introduced.

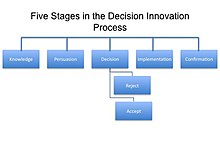

[39] In later editions of Diffusion of Innovation, Rogers changes his terminology of the five stages to: knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation.

Another strategy includes injecting an innovation into a group of individuals who would readily use said technology, as well as providing positive reactions and benefits for early adopters.

For example, Rogers discussed a situation in Peru involving the implementation of boiling drinking water to improve health and wellness levels in the village of Los Molinos.

The campaign worked with the villagers to try to teach them to boil water, burn their garbage, install latrines and report cases of illness to local health agencies.

While people might hear of an innovation's uses, in Rogers' Los Molinos sanitation case, a network of influence and status prevented adoption.

Using their definition, Rogers defines homophily as "the degree to which pairs of individuals who interact are similar in certain attributes, such as beliefs, education, social status, and the like".

Homophilous individuals engage in more effective communication because their similarities lead to greater knowledge gain as well as attitude or behavior change.

Research was done in the early 1950s at the University of Chicago attempting to assess the cost-effectiveness of broadcast advertising on the diffusion of new products and services.

The lowest levels were generally larger in numbers and tended to coincide with various demographic attributes that might be targeted by mass advertising.

Prior to the introduction of the Internet, it was argued that social networks had a crucial role in the diffusion of innovation particularly tacit knowledge in the book The IRG Solution – hierarchical incompetence and how to overcome it.

[61] Recent research by Wear shows, that particularly in regional and rural areas, significantly more innovation takes place in communities which have stronger inter-personal networks.

Research indicated that, with proper initial screening procedures, even simple behavioral model can serve as a good predictor for technology adoption in many commercial organizations.

At the local level, examining popular city-level policies make it easy to find patterns in diffusion through measuring public awareness.

[70] At the international level, economic policies have been thought to transfer among countries according to local politicians' learning of successes and failures elsewhere and outside mandates made by global financial organizations.

[71] As a group of countries succeed with a set of policies, others follow, as exemplified by the deregulation and liberalization across the developing world after the successes of the Asian Tigers.

[73] Eveland evaluated diffusion from a phenomenological view, stating, "Technology is information, and exists only to the degree that people can put it into practice and use it to achieve values".

Bass (1969)[80] and many other researchers proposed modeling the diffusion based on parametric formulas to fill this gap and to provide a means for a quantitative forecast of adoption timing and levels.

[84] In threshold models,[85] the uptake of technologies is determined by the balance of two factors: the (perceived) usefulness (sometimes called utility) of the innovation to the individual as well as barriers to adoption, such as cost.

[86] Computer models are often used to investigate this balance between the social aspects of diffusion and perceived intrinsic benefit to the individuals.

[92] In complex environments where the adopter is receiving information from many sources and is returning feedback to the sender, a one-way model is insufficient and multiple communication flows need to be examined.