Diocletian's Palace

The complex was built on a peninsula six kilometres (3.7 mi) southwest from Salona, the former capital of Dalmatia, one of the largest cities of the late empire with 60,000 people and the birthplace of Diocletian.

The terrain around Salona slopes gently seaward and is typical karst, consisting of low limestone ridges running east to west with marl in the clefts between them.

Based on Roman map data (known through the medieval parchment copy of the Tabula Peutingeriana), there was already a Spalatum settlement in that bay, the remains and size of which have not yet been established.

At Carnuntum, people begged Diocletian to return to the throne in order to resolve the conflicts that had arisen through Constantine's rise to power and Maxentius' usurpation.

[3] Diocletian famously replied: If you could show the cabbage that I planted with my own hands to your emperor, he definitely wouldn't dare suggest that I replace the peace and happiness of this place with the storms of a never-satisfied greed.

[5][6][Note 1] With the death of Diocletian, the life of the palace did not end, and it remained an imperial possession of the Roman court, providing shelter to the expelled members of the Emperor's family.

Its second life came when Salona was largely destroyed in the invasions of the Avars and Slavs in the 7th century, though the exact year of the destruction still remains an open debate between archaeologists.

Part of the expelled population, now refugees, found shelter inside the palace's strong walls and with them a new, organized city life began.

Also completed in this period was the construction of the Romanesque bell tower of the Cathedral of Saint Domnius, which inhabits the building that was originally erected as Jupiter's temple and then used as the Mausoleum of Diocletian.

[10] After the Middle Ages, the palace was virtually unknown in the rest of Europe until the Scottish architect Robert Adam had the ruins surveyed.

Then, with the aid of French artist and antiquary Charles-Louis Clérisseau and several draughtsmen, Adam published Ruins of the Palace of Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia (London, 1764).

A few decades later, in 1782, the French painter Louis-François Cassas created drawings of the palace, published by Joseph Lavallée in 1802 in the chronicles of his voyages.

The World Monuments Fund has been working on a conservation project at the palace, including surveying structural integrity and cleaning and restoring the stone and plasterwork.

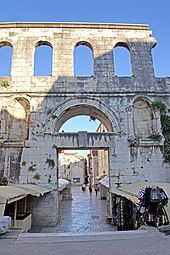

The southern 'Sea Gate' (the Porta Meridionalis) was simpler in shape and dimensions than the other three, and it is thought that it was originally intended either as the emperor's private access to the sea or as a service entrance for supplies.

During the persecutions under Theodosius I a relief sculpture of Nike, the Roman goddess of Victory (which stood on the lintel) was removed from the gate, later in the 5th century, Christians engraved a Cross in its place.

In the southern half there were more luxurious structures than in the northern section; these included public, private and religious buildings, as well as the Emperor's apartments.

Diocletian's apartment was interconnected by a long room along the southern façade (cryptoporticus)[25] from which through 42 windows and 3 balconies a view of the sea was opened.

The northern half of the palace, divided into two parts by the main north–south street (cardo) leading from the Golden Gate (Porta aurea) to the Peristyle, is less well preserved.

Both parts of the palace were apparently surrounded by streets,[14] leading to the perimeter walls through a rectangular buildings (possibly storage magazines).

Some material for decoration was imported: Egyptian granite columns, fine marble for revetments and some capitals produced in workshops in the Proconnesos.

The Palace was decorated with numerous 3500-year-old granite sphinxes, originating from the site[dubious – discuss] of Egyptian Pharaoh Thutmose III.