Diplomacy of the American Civil War

The United States prevented other powers from recognizing the Confederacy, which counted heavily on Britain and France to enter the war on its side to maintain their supply of cotton and to weaken a growing opponent.

France encouraged Britain to join in a policy of mediation, suggesting that both recognize the Confederacy,[2] while Abraham Lincoln warned that any such recognition was tantamount to a declaration of war.

Knowing a war would cut off vital shipments of American food, wreak havoc on the British merchant fleet, and cause an invasion of Canada, Britain and its powerful Royal Navy refused to join France.

Confederate spokesmen, on the other hand, were much more successful: ignoring slavery and instead focusing on their struggle for liberty, their commitment to free trade, and the essential role of cotton in the European economy.

Most European leaders were unimpressed with the Union's legal and constitutional arguments and thought it hypocritical that the U.S. should seek to deny to one of its regions the same sort of independence it won from Great Britain some eight decades earlier.

Even more importantly, the European aristocracy (the dominant factor in every major country) was "absolutely gleeful in pronouncing the American debacle as proof that the entire experiment in popular government had failed.

Attempts by the Lincoln administration to join the Paris Declaration then were rejected by Great Britain and France, who accused the Union of trying to use European navies to wage maritime war against the Confederates.

[19][22][23] The first commissioners named by CS President Jefferson Davis on February 1861 were William Lowndes Yancey to France and Britain, Pierre Adolphe Rost to Spain, and Ambrose Dudley Mann to Belgium and the Vatican, with journalist Edwin de Leon as their adviser and chief Confederate propagandist in Europe.

[24] By early 1862, vice president Alexander H. Stephens and others considered Confederate diplomatic efforts such failures that he suggested withdrawing all agents and representatives from abroad and using the resources on the battlefield.

Davis ignored this and appointed Judah P. Benjamin as secretary of state, who worked to forge a closer relationship with France, sell cotton at "remarkably low prices" and engage in arms purchases from French and British suppliers to link their commercial interests more closely with the Confederacy.

[25] Confederate agent Father John B. Bannon was a Catholic priest who traveled to Rome in 1863 in a failed attempt to convince Pope Pius IX to grant diplomatic recognition to the Confederacy.

He was very pleased with the Confederate victory at Bull Run in July 1861, but 15 months later he wrote that: The American War ... has manifestly ceased to have any attainable object as far as the Northerns are concerned, except to get rid of some more thousand troublesome Irish and Germans.

The issues facing the British textile industry factored into the debate over intervening on behalf of the Confederacy in order to break the Union blockade and regain access to Southern cotton.

Many British leaders expected an all-out race war to break out in the American South, with so many tens or hundreds of thousands of deaths that humanitarian intervention was called for to prevent the threatened bloodshed.

Gladstone had a favorable image of the Confederacy and urged humanitarian intervention because of the staggering death toll, the risk of a race war, and the failure of the Union to achieve decisive military results.

[citation needed] In rebuttal, Secretary of War Sir George Cornewall Lewis opposed intervention as a high-risk proposition that could result in massive losses.

[53] A long-term issue was the British shipyard (John Laird and Sons) building two warships for the Confederacy, especially the CSS Alabama, over vehement protests from the United States government.

The controversy was resolved after the war in the Treaty of Washington which included the resolution of the Alabama Claims whereby Britain gave the United States $15.5 million after arbitration by an international tribunal for damages caused by British-built warships.

Alone among European powers, Russia offered oratorical support for the Union, largely due to the view that the United States served as a counterbalance to the British Empire.

Once the Union won the war in spring 1865, the U.S. allowed supporters of Juárez to openly purchase weapons and ammunition and issued stronger warnings to Paris.

[82] Many Hawaiians sympathized with the Union because of Hawaii's ties to New England through its missionaries and whaling industries, and the opposition of many to the institution of slavery, which the Constitution of 1852 had officially outlawed.

The American consul in Kanagawa, Colonel Fisher, blamed the diplomacy of the French Jesuit Mermet de Cachon the most, perceiving the British as a lesser threat represented only by their global naval and military power.

[90] Pruyn's request of naval protection from Washington was unheeded, but he got an answer from the USS Wyoming, which had been sent to Asia to pursue the CSS Alabama and was fortuitously in Hong Kong.

"[90] Without waiting for approval from Washington, the Wyoming sailed to Shimonoseki and on 16 July engaged the daimyo's three ships while under fire from coastal artillery, sinking two and damaging the other, along with one battery,[91] before retiring due to lacking depth charts of the area.

"[90] In any case, the action of the Wyoming was immediately dwarfed by the French burning of Shimonoseki on 24 July and the British bombardment of Kagoshima in August, both in response to Japanese attacks against them.

One year later, a fleet of British, French, and Dutch warships, accompanied by one American man-of-war as a sign of support, destroyed Chōshū's military capability at Shimonoseki and forced the daimyo to capitulate.

[88] On 14 February 1861 (the last month of the Buchanan administration), King Mongkut of Siam wrote a diplomatic letter addressed to the President of the United States in Washington, D.C., expressing his desire to have friendly relations with the country.

[92] Lincoln wrote a reply on 3 February 1862, accepting the gifts on behalf of the American people, but politely declined living elephants under the reasoning that the geography of the United States was not favorable for their multiplication, and the steam engine was sufficient to cover its transportation needs.

These actions satisfied Union diplomats, who disapproved of the European intervention in North America, allowing the United States and Austria to maintain friendly relations through the close of the Civil War.

The arbitration of the Alabama Claims in 1872 provided a satisfactory reconciliation; the British paid the United States $15.5 million for the economic damage caused by Confederate warships purchased from it.

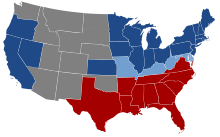

Light Blue : Slave states that did not secede

Red : Confederate States

Gray : Non-autonomous territories