Millipede

Millipedes (originating from the Latin mille, "thousand", and pes, "foot")[1][2] are a group of arthropods that are characterised by having two pairs of jointed legs on most body segments; they are known scientifically as the class Diplopoda, the name derived from this feature.

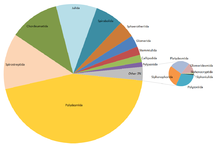

[3] There are approximately 12,000 named species classified into 16 orders and around 140 families, making Diplopoda the largest class of myriapods, an arthropod group which also includes centipedes and other multi-legged creatures.

Its primary defence mechanism is to curl into a tight coil, thereby protecting its legs and other vital delicate areas on the body behind a hard exoskeleton.

Millipedes can be distinguished from the somewhat similar but only distantly related centipedes (class Chilopoda), which move rapidly, are venomous, carnivorous, and have only a single pair of legs on each body segment.

There are two major groups of millipedes whose members are all extinct: the Archipolypoda ("ancient, many-legged ones") which contain the oldest known terrestrial animals, and Arthropleuridea, which contain the largest known land invertebrates.

Pneumodesmus newmani is the earliest member of the millipedes from the late Wenlock epoch of the late Silurian around 428 million years ago,[17][18] or early Lochkovian of the early Devonian around 414 million years ago,[19][20] known from 1 cm (1⁄2 in) long fragment and has clear evidence of spiracles (breathing holes) attesting to its air-breathing habits.

[14] The history of scientific millipede classification began with Carl Linnaeus, who in his 10th edition of Systema Naturae, 1758, named seven species of Julus as "Insecta Aptera" (wingless insects).

[24] In 1802, the French zoologist Pierre André Latreille proposed the name Chilognatha as the first group of what are now the Diplopoda, and in 1840 the German naturalist Johann Friedrich von Brandt produced the first detailed classification.

From 1890 to 1940, millipede taxonomy was driven by relatively few researchers at any given time, with major contributions by Carl Attems, Karl Wilhelm Verhoeff and Ralph Vary Chamberlin, who each described over 1,000 species, as well as Orator F. Cook, Filippo Silvestri, R. I. Pocock, and Henry W.

The extinct Arthropleuridea was long considered a distinct myriapod class, although work in the early 21st century established the group as a subclass of millipedes.

[32] Both groups of myriapods share similarities, such as long, multi-segmented bodies, many legs, a single pair of antennae, and the presence of postantennal organs, but have many differences and distinct evolutionary histories, as the most recent common ancestor of centipedes and millipedes lived around 450 to 475 million years ago in the Silurian.

[12][13] They have also lost the gene that codes for the JHAMTl enzyme, which is responsible for catalysing the last step of the production of a juvenile hormone that regulates the development and reproduction in other arthropods like crustaceans, centipedes and insects.

[39] The head of a millipede is typically rounded above and flattened below and bears a pair of large mandibles in front of a plate-like structure called a gnathochilarium ("jaw lip").

[36] Because they can't close their permanently open spiracles and most species lack a waxy cuticle, millipedes are susceptible to water loss and with a few exceptions must spend most of their time in moist or humid environments.

[9][36] Millipedes in several orders have keel-like extensions of the body-wall known as paranota, which can vary widely in shape, size, and texture; modifications include lobes, papillae, ridges, crests, spines and notches.

[48] The genital openings (gonopores) of both sexes are located on the underside of the third body segment (near the second pair of legs) and may be accompanied in the male by one or two penes which deposit the sperm packets onto the gonopods.

Copulation may be preceded by male behaviours such as tapping with antennae, running along the back of the female, offering edible glandular secretions, or in the case of some pill-millipedes, stridulation or "chirping".

[36] Millipedes occur on all continents except Antarctica, and occupy almost all terrestrial habitats, ranging as far north as the Arctic Circle in Iceland, Norway, and Central Russia, and as far south as Santa Cruz Province, Argentina.

[32][52] Deserticolous millipedes, species evolved to live in the desert, like Orthoporus ornatus, may show adaptations like a waxy epicuticle and the ability of water uptake from unsaturated air.

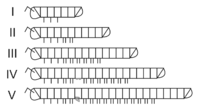

Flat-backed millipedes in the order Polydesmida tend to insert their front end, like a wedge, into a horizontal crevice, and then widen the crack by pushing upwards with their legs, the paranota in this instance constituting the main lifting surface.

These have smaller segments at the front and increasingly large ones further back; they propel themselves forward into a crack with their legs, the wedge-shaped body widening the gap as they go.

This may be because they are too small to have enough leverage to burrow, or because they are too large to make the effort worthwhile, or in some cases because they move relatively fast (for a millipede) and are active predators.

[43] Where earthworm populations are low in tropical forests, millipedes play an important role in facilitating microbial decomposition of the leaf litter.

[68] Due to their lack of speed and their inability to bite or sting, millipedes' primary defence mechanism is to curl into a tight coil – protecting their delicate legs inside an armoured exoskeleton.

[69] Many species also emit various foul-smelling liquid secretions through microscopic holes called ozopores (the openings of "odoriferous" or "repugnatorial glands"), along the sides of their bodies as a secondary defence.

Primates such as capuchin monkeys and lemurs have been observed intentionally irritating millipedes in order to rub the chemicals on themselves to repel mosquitoes.

[78] The bristly millipedes (order Polyxenida) lack both an armoured exoskeleton and odiferous glands, and instead are covered in numerous bristles that in at least one species, Polyxenus fasciculatus, detach and entangle ants.

Some millipedes are considered household pests, including Xenobolus carnifex which can infest thatched roofs in India,[90] and Ommatoiulus moreleti, which periodically invades homes in Australia.

Other species exhibit periodical swarming behaviour, which can result in home invasions,[91] crop damage,[92] and train delays when the tracks become slippery with the crushed remains of hundreds of millipedes.

[105] In biology, some authors have advocated millipedes as model organisms for the study of arthropod physiology and the developmental processes controlling the number and shape of body segments.