Discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun

The publicity surrounding the excavation intensified when Carnarvon died of an infection, giving rise to speculation that his death and other misfortunes connected with the tomb were the result of an ancient curse.

It was more informative about the material culture of Tutankhamun's time, demonstrating what a complete royal burial was like and providing evidence about the lifestyles of wealthy Egyptians and the behaviour of ancient tomb robbers.

Since the discovery, the Egyptian government has capitalised on its enduring fame by using exhibitions of the burial goods for purposes of fundraising and diplomacy, and Tutankhamun has become a symbol of ancient Egypt itself.

[19] After the Antiquities Service transferred Carter to Lower Egypt in 1904, Davis held the concession to excavate in the valley for another ten years, his efforts managed by a series of five archaeologists.

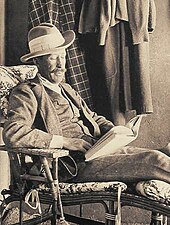

"[27] Carter left the Antiquities Service in 1905 after a group of French tourists forced their way into a closed archaeological site at Saqqara and he ordered the Egyptian guards to eject them.

This area was difficult to clear because it included the remains of ancient workers' huts and lay close to the entrance to KV9, which attracted heavy tourist traffic.

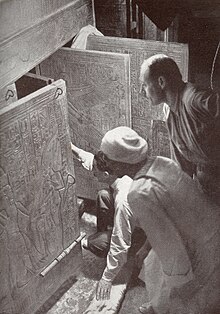

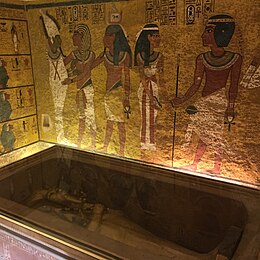

[53] Carter, Carnarvon and Lady Evelyn Herbert squeezed through the hole to find the tomb's burial chamber, which was mostly filled by the set of gilded shrines that enclosed Tutankhamun's sarcophagus.

[55] Carter, in particular, may have wanted to be certain of that fact; in 1900 he had opened what he thought was an undisturbed royal tomb, the Bab el-Hosan, in front of many highly placed guests, only to find it nearly empty.

T. G. H. James, Carter's biographer, argued that entering the burial chamber, before the site had been inspected by officials from the Antiquities Service, did not violate the terms of Carnarvon's concession or the standards of behaviour among archaeologists in the 1920s.

[58] Joyce Tyldesley asserts that it was against the terms of the concession and points out that the breach necessitated moving some of the artefacts that stood in front of the partition, meaning their original positions could not be recorded.

[61] He needed assistance, and he called upon Albert Lythgoe, head of the Egyptian Expedition of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which was working nearby, to loan some of its personnel.

Lythgoe sent Mace, a specialist in conservation; Harry Burton, regarded as the best archaeological photographer in Egypt; and the architect Walter Hauser and the artist Lindsley Hall, who drew scale drawings of the antechamber and its contents.

[62] Other experts also volunteered their services: Alfred Lucas, a chemist for the Antiquities Service, whose expertise would be a great help in the conservation effort; James Henry Breasted and Alan Gardiner, two of the foremost scholars of the Egyptian language of the time, to translate any texts discovered in the tomb; and Percy Newberry, a specialist of botanical specimens, and his wife Essie, who helped conserve textiles from the burial.

"[70] The disorganised contents of boxes had to be sorted through, and in some cases pieces of a single object, such as an elaborate inlaid corselet, were scattered through the chamber and had to be searched for before being reassembled.

Guests at the Winter Palace Hotel in Luxor danced to the "Tutankhamun Rag",[79] and in the United States the discovery inspired a flurry of ephemeral Egypt-themed films and a more enduring hit song, "Old King Tut".

An editorial in Al-Ahram, written by Fikri Abaza, declared "Lord Carnarvon is exploiting the mortal remains of our ancient fathers before our eyes, and he fails to give the grandchildren any information about their forefathers".

This regulation has since become standard on Egyptological digs but was novel at the time, and in this case it was clearly aimed at Merton, whom Carter had appointed as a member of the excavation team.

This change did not apply to Carnarvon's existing concession, which allowed for a division of finds except in case of an intact tomb, whose contents must be surrendered entirely to the Antiquities Service.

Lythgoe, Gardiner, Breasted and Newberry sent a letter of protest to Lacau and his superior, the minister of public works, asserting that the Tutankhamun discovery "belongs not to Egypt alone but to the entire world".

[144] The letter thus went to the Wafd's new minister of public works, Morcos Bey Hanna,[143] who was not inclined to be accommodating towards Britons, as the British government had put him on trial for treason for his actions during the Revolution of 1919.

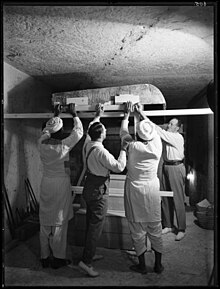

On 12 February, the lid was raised, revealing, beneath a shroud, a gilded and inlaid wooden coffin in human shape, bearing Tutankhamun's face – the outermost of a nested set.

[148] Hanna saw this tour as a slight – he pointed out that wives of Egyptian cabinet ministers had not been allowed into the tomb[149] – and forbade the families' visit, sending a police force to ensure his order was carried out.

His absence eased the tensions surrounding the tomb, as did the impending retirement of Maxwell, who began transferring his responsibilities to a more conciliatory lawyer, Georges Merzbach.

Among the materials stored in the tombs, they discovered a wooden bust of Tutankhamun emerging from a lotus flower, packed in a crate, that was not included in Carter's excavation notes.

[181] When resuming work in the fifth season Carter rearranged the pieces of the mummy to look whole once again, then placed them in the outermost coffin and covered the sarcophagus with a plate of glass instead of the original lid.

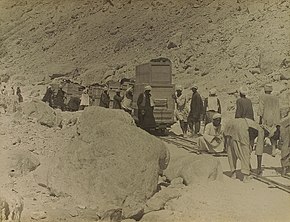

With this done, the excavators dismantled the barrier to the treasury and began sorting through its contents: a shrine of the god Anubis, more boxes of belongings such as jewellery, wooden tomb models of boats and the canopic chest that contained the internal organs that were removed from Tutankhamun's body during embalming.

[212][213] Much of the tomb's historical value was in the burial goods, which included sumptuous examples of ancient Egyptian decorative arts and enhanced the understanding of the material culture of the New Kingdom, primarily how royalty lived.

[225] Although Western public interest in Tutankhamun experienced a lull lasting more than thirty years, it was revived after the Egyptian government began sending the burial goods on international museum exhibitions.

[168] The exhibitions began in the early 1960s as a means of encouraging Western support for the relocation of ancient Egyptian monuments that were threatened to be flooded by the construction of the Aswan High Dam.

[229] The exhibitions also served other diplomatic functions, helping to improve Egypt's relations with Britain and France after the Suez Crisis in 1956, and with the United States after the Yom Kippur War in 1973.