Disinformation attack

[4] Disinformation can be considered an attack when it occurs as an adversarial narrative campaign that weaponizes multiple rhetorical strategies and forms of knowing—including not only falsehoods but also truths, half-truths, and value-laden judgements—to exploit and amplify identity-driven controversies.

[8][9] Digital tools such as bots, algorithms, and AI technology, along with human agents including influencers, spread and amplify disinformation to micro-target populations on online platforms like Instagram, Twitter, Google, Facebook, and YouTube.

Disinformation attacks involve the intentional spreading of false information, with end goals of misleading, confusing, and encouraging violence,[24] and gaining money, power, or reputation.

[44][45] Whether disinformation attacks are used against political opponents or "commercially inconvenient science", they sow doubt and uncertainty as a way of undermining support for an opposing position and preventing effective action.

[51] If claims of voter fraud are being put forward, provide clear messaging about how the voting process occurs, and refer people back to reputable sources that can address their concerns.

[15] For example, a New Yorker report in 2023 revealed details about the campaign run by the UAE, under which the Emirati President Mohamed bin Zayed paid millions of euros to a Swiss businessman, Mario Brero, for "dark PR" against their targets.

Brero and his company Alp Services used the UAE money to create damning Wikipedia entries and publish propaganda articles against Qatar and those with ties to the Muslim Brotherhood.

[14][54] Sudip Parikh, CEO of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in 2022 is quoted as saying "We now have a significant minority of the population that's hostile to the scientific enterprise... We're going to have to work hard to regain trust.

[79] A Russian operation known as the Internet Research Agency (IRA) spent thousands on social media ads to influence the 2016 United States presidential election, confuse the public on key political issues and sow discord.

Alt-right media personalities including Britain's Paul Joseph Watson and American Jack Posobiec prominently shared MacronLeaks content prior to the French election.

[9] In A Lot of People Are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy (2020) Nancy L. Rosenblum and Russell Muirhead examine the history and psychology of conspiracy theories and the ways in which they are used to de-legitimize the political system.

Public-relations firms may be hired to execute specialized disinformation campaigns, including media advertisements and behind-the-scenes lobbying, to push the narrative of an honest and democratic election.

Government organizations and independent journalistic groups such as Bellingcat work to confirm or deny such reports, often using open-source data and sophisticated tools to identify where and when information has originated and whether claims are legitimate.

[53][88] As has been painstakingly documented, the period leading up to the Holocaust was marked by repeated disinformation and increasing persecution by the Nazi government,[96][97] culminating in the mass murder[98] of 165,200 German Jews[99] by a "genocidal state".

Countries such as Kenya whose history has involved ethnic or election-related violence, foreign or domestic interference, and a high reliance on the use of social media for political discourse, are considered to be at higher risk.

Recognition of the seriousness of this problem is essential, to mobilize governments, civic society, and social media platforms to take steps to prevent both online and offline harm.

[111][112][101] Kettering, Midgley and Kehoe emphasized that a gas additive was needed, and argued that until "it is shown ... that an actual danger to the public is had as a result",[109] the company should be allowed to produce its product.

[6] Within the United States, sharing of disinformation and propaganda has been associated with the development of increasingly "partisan" media, most strongly in right-wing sources such as Breitbart, The Daily Caller, and Fox News.

[2][131][132] An app called "Dawn of Glad Tidings," developed by Islamic State members, assists in the organization's efforts to rapidly disseminate disinformation in social media channels.

This app allows for automated Tweets to be sent out from real user accounts and helps create trends across Twitter that amplify disinformation produced by the Islamic State on an international scope.

[150] The 2023 Summit on "Truth, Trust, and Hope", held by the Nobel Committee and the US National Academy of Science, identified disinformation as more dangerous than any other crisis, because of the way in which it hampers the addressing and resolution of all other problems.

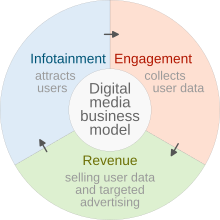

[77] Existing social, legal and regulatory guidelines may not apply easily to actions in an international virtual world, where private corporations compete for profitability, often on the basis of user engagement.

"Democracies should not seek to covertly influence public debate either by deliberately spreading information that is false or misleading or by engaging in deceptive practices, such as the use of fictitious online personas.

"[154] Further, democracies are encouraged to play to their strengths, including rule of law, respect for human rights, cooperation with partners and allies, soft power, and technical capability to address cyber threats.

[152][149] There is an underlying assumption that identifiable parties will have the opportunity to share their views on a relatively level playing field, where a public figure being drawn into a debate will have increased access to the media and a chance of rebuttal.

[159] This may no longer hold true when rapid, massive disinformation attacks are deployed against an individual or group through anonymous or multiple third parties, where "A half-day's delay is a lifetime for an online lie.

[164] DSA aims to harmonise differing laws at the national level in the European Union[162] including Germany (NetzDG), Austria ("Kommunikationsplattformen-Gesetz") and France ("Loi Avia").

[19][177] Algorithms that push content based on user search histories, frequent clicks and paid advertising leads to unbalanced, poorly sourced, and actively misleading information.

The order issued by United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in 2023 "severely limits the ability of the White House, the surgeon general, [and] the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention... to communicate with social media companies about content related to COVID-19... that the government views as misinformation".

Finland, the highest ranking country, has developed an extensive curriculum that teaches critical thinking and resistance to information warfare, and integrated it into its public education system.