Dispute between Darnhall and Vale Royal Abbey

In the early fourteenth century, tensions between villagers from Darnhall and Over, Cheshire, and their feudal lord, the Abbot of Vale Royal Abbey, erupted into violence over whether they had villein—that is, servile—status.

This was primarily because it had been granted, in its endowment, exclusive forest rights which surrounding villages saw as theirs by custom, and other feudal dues they did not believe they had to pay.

Their house had commenced major building works in 1277, but then lost much of its early royal funding following Edward I's invasion of Wales the same year, which diverted both his money and masons from them.

The villagers met him in Rutland on his return journey; an affray broke out, the Abbot's groom was killed, and Peter and his entourage were captured.

The Cistercian Abbey of Vale Royal, in the Weaver Valley, was originally founded by the Lord Edward—later King Edward I—in 1274, in gratitude for his safe passage through a storm on the return from crusade.

Originally intended to be a grand, cathedral-style structure with a complement of 100 monks, building started in 1277 under the King's chief architect, Walter of Hereford.

[8] Historians Christopher Harper-Bill and Carole Rawcliffe have highlighted the ruthlessness of religious landlords in the Middle Ages, noting their skill in "exploiting every source of income"[9] and the unpopularity this brought on them.

[9][note 2] As the medievalists Gwilym Dodd and Alison McHardy have emphasised, "a religious house, like any other landlord, depended on the income from its estates as the main source of its economic wellbeing",[11] and from the late twelfth century, monastic institutions were "particularly assiduous in... seeking to tighten the legal definition of servile status and tenure" for its tenantry.

[12][13] Likewise, Bec Abbey's tenants in Ogbourne St George, Wiltshire, launched a well-organised peasant's revolt in 1309, which also found some support amongst local gentry.

[17] Darnhall, previously a royal manor held by the earls of Chester, had been granted to the Abbey in perpetuity, along with its forestry rights and free warren.

[30] Although the villeins of Vale Royal's estate owed no labour service for their land, the villagers of Darnhall and those who joined them remained unhappy with their situation.

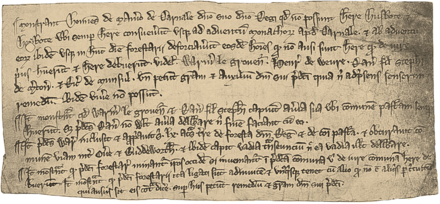

[18] The abbot was on his return to his monastery, and a great crowd of the country people of Dernehale came to meet him in the highway on the feast of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist, about the ninth hour, at Exton in the county of Rutland; and they attacked him, and slew his groom, William Fynche, with an arrow in a place called Grene Delues.

And there was also with them William de Venables of Bradewell, who at that time was suing the aforesaid abbot on account of Thomas de Venables, his brother, which Thomas claimed that he was of right entitled to fish in the stew of Dernehale; and when he saw that the aforesaid William Fynche was slain by his aid and help, he took to flight, and did not dare to stay his foot till he came to the parts of Chestershire, and he contemptibly abandoned those he had brought with him, and never looked behind him.

Now Walter Welsh, the cellarer, and John Coton, and others of the abbot's servants were about half a league behind the abbot, having tarried for certain business; and when they saw the fight from afar they came up at full speed, and the said armed bondmen came up against them to assault them; but the aforesaid cellarer (blessed be his memory), like a champion sent from God to protect his house and father, though he was all unarmed, not without enormous bloodshed felled those sacrilegious men to the earth, and left all those whom he found in that place half dead, according to the law of the Lord (in lege d'ni).

There was no such thing, says Edward Powell, "as cheap litigation",[40][note 9] although there was plenty of it; Richard Firth Green has commented that "what strikes one... is not the lawlessness of the Abbey's tenants but their touching faith in the legal process".

On his return journey, passing the village of Exton, Peter and his entourage were set upon by what the Ledger Book called a "great crowd of the country people"[51] from Darnhall.

[53] However, the following day, the King, hearing of events, ordered Peter's release, and the arrest of his captors, who were taken to Stamford and imprisoned in chains in "the greatest of misery".

[46] Recording how the people firstly complained to the Chester justiciar, then petitioned parliament, and finally sent a deputation to present their case to the King at Windsor, the writer concluded they were behaving "like mad dogs".

[34] As with any lord in the Middle Ages, when his authority was questioned by those of lower social strata, the law would almost inherently find for him; but, notes Hewitt, it would also "be idle to identify legality with justice".

Peter was engaged in a spirited defence of his house's rights and prerogatives against Sir Thomas de Venables, who is known to have launched similar raids.

[56][note 15] Before the Abbot's and Welch's deaths, a number of the Abbey's buildings were destroyed, much of the harvest burnt, goods stolen and livestock killed.

The Ledger Book records that in 1340 two monks were charged with murdering two local men, Robert Hykes and John Bulderdog,[63] and that de Cheyneston himself was arraigned and fined for appropriating burgages belonging to Over.

[65] Mark Bailey says, "villein tenures were, in fact, in headlong retreat from the 1350s, and had largely decayed by the 1380s",[66] with what remaining being seasonal work, such as harvest time.

[66] Conversely, Alan Harding argues, albeit on a national level, that the number of commissions of oyer and terminer[note 16]—investigations headed by a assize judge—into the "rebellious"[46] withdrawal of feudal labour by villeins indicates that such conspiracies continued up until the 1381 Rising.

[46] It is detestable in a monk that, under any custom of colour, or honour, or title of power, he should possess feudal rights and bondmen and bondwomen, or homages and fealties and allegiances, or that he should lay forced labour upon them, and extra-services and other burdens of public works.