District heating

[21][22] In this case the distinguishing feature is a unique access to an abandoned water-filled coal mine within the city boundary that provides a stable heat source for the system.

[25] This burning of fossil hydrocarbons usually contributes to climate change, as the use of systems to capture and store the CO2 instead of releasing it into the atmosphere is rare.

[32][clarification needed] Since nuclear reactors do not significantly contribute to either air pollution or global warming, they can be an advantageous alternative to the combustion of fossil hydrocarbons.

An example is a 14 MW(thermal) district heating network in Drammen, Norway, which is supplied by seawater-source heatpumps that use R717 refrigerant, and has been operating since 2011.

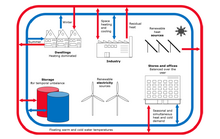

[57] In the future, industrial heat pumps will be further de-carbonised by using, on one side, excess renewable electrical energy (otherwise spilled due to meeting of grid demand) from wind, solar, etc.

It also allows solar heat to be collected in summer and redistributed off season in very large but relatively low-cost in-ground insulated reservoirs or borehole systems.

The axial expansion of the pipes is partially counteracted by frictional forces acting between the ground and the casing, with the shear stresses transferred through the PU foam bond.

Also, the thermal efficiency of cogeneration plants is significantly lower if the cooling medium is high-temperature steam, reducing electric power generation.

[68][69] This led to great inefficiencies – users had to simply open windows when too hot – wasting energy and minimising the numbers of connectable customers.

Some schemes may be designed to serve only a limited number of dwellings, of about 20 to 50 houses, in which case only tertiary sized pipes are needed.

District heating networks, heat-only boiler stations, and cogeneration plants require high initial capital expenditure and financing.

They have compiled an analysis of district heating and cooling markets in Europe within their Ecoheatcool project supported by the European Commission.

[78] Other UK measures to encourage CHP growth are financial incentives, grant support, a greater regulatory framework, and government leadership and partnership.

The largest system is in the capital Sofia, where there are four power plants (two CHPs and two boiler stations) providing heat to the majority of the city.

Over 90% of apartment blocks, more than half of all terraced houses, and the bulk of public buildings and business premises are connected to a district heating network.

Renewables, such as wood chips and other paper industry combustible by-products, are also used, as is the energy recovered by the incineration of municipal solid waste.

Today District heating installations are also available in Kozani, Ptolemaida, Amyntaio, Philotas, Serres and Megalopolis using nearby power plants.

[99] There are 117 local district heating systems supplying towns as well as rural areas with hot water – reaching almost all of the population.

[100] The Reykjavík Capital Area district heating system serves around 230,000 residents had a maximum thermal power output of 830 MW.

Heat is supplied from the Hellisheiði (200MWth) and Nesjavellir (300MWth) CHP plants, as well as a few lower temperature fields inside Reykjavik.

Heating demand has increased steadily as the population has grown, necessitating enlargement of thermal water production in the Hellisheiði CHP plant.

District heating is used in Rotterdam,[111][112] Amsterdam, Utrecht,[113] and Almere[114] with more expected as the government has mandated a transition away from natural gas for all homes in the country by 2050.

Balkan Energy Group (BEG) operates three DH production plants, which cover majority of the network, and supply heat to around 60,000 households in Skopje, more than 80 buildings in the educational sector (schools and kindergartens) and more than 1,000 other consumers (mostly commercial).

The largest coverage with the district heating system and the lowest price is in Velenje, where all city facilities are connected, so there are no local or individual fireplaces.

Warm and hot water are the most common heat carriers, but older high-pressure steam transport still accounts for around one-quarter of the primary distribution, which results in more losses in the system.

The state owns and operates large co-generation plants that produce district heat and electricity in six cities (Bratislava, Košice, Žilina, Trnava, Zvolen and Martin).

It is still in operation; the water is now heated locally by a new energy centre which incorporates 3.1 MWe / 4.0 MWth of gas fired CHP engines and 3 × 8 MW gas-fired boilers.

It saves an equivalent 21,000 plus tonnes of CO2 each year when compared to conventional sources of energy – electricity from the national grid and heat generated by individual boilers.

It supplies heating and district cooling to many large premises in the city, including the Westquay shopping centre, the De Vere Grand Harbour hotel, the Royal South Hants Hospital, and several housing schemes.

[191] In February 2019, China's State Power Investment Corporation (SPIC) signed a cooperation agreement with the Baishan municipal government in Jilin province for the Baishan Nuclear Energy Heating Demonstration Project, which would use a China National Nuclear Corporation DHR-400 (District Heating Reactor 400 MWt).