District of Columbia retrocession

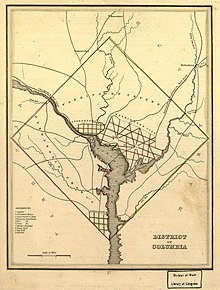

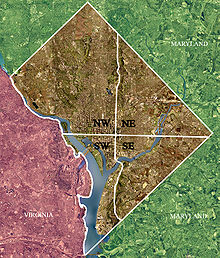

[weasel words] In the 1790 Residence Act[1] the District originally consisted of 100 square miles (259 km2; 25,900 ha) of land, which was ceded to it by Maryland and Virginia, and it straddled the Potomac River.

The 1801 Organic Act placed the areas under the control of the United States Congress and removed the right of residents to vote in federal elections.

The portion west of the Potomac River, ceded by Virginia, included two parts comprising 31 square miles (80 km2; 8,029 ha): the city of Alexandria, at the extreme southern shore, and the rural and short-lived Alexandria County, D.C. After decades of debate about the disenfranchisement that came with district citizenship, and tensions related to perceived negligence by the U.S. Congress, this portion of the district was returned to Virginia in 1847.

[6][7] Following the 1801 Act, citizens located in the District were no longer considered residents of Maryland or Virginia, thus ending their representation in Congress, their ability to weigh in on Constitutional amendments, and their unlimited home rule.

[8] Ever since, residents of the District and the surrounding states have sought ways to remedy these issues, with the most common being retrocession, statehood, and constitutional amendment.

[9] While representation is often cited as a grievance of District residents, limited self-rule has often played a large or larger part in retrocession movements.

[4] In 1975, the District government was reorganized with citizens allowed to elect their own mayor and city council members, but all laws were subject to Congressional review, which has been used in limited, but notable ways.

[citation needed] There were Federal bills to reunite the southern portion of the District with Virginia as early as 1803, but it was only in the late 1830s that these garnered local support.

[12] Early efforts, supported by the Democratic-Republicans, focused on the lack of home rule and were often combined with retrocession of some or all of the area north of the Potomac as well.

[13] Similar efforts in Georgetown and dissatisfaction elsewhere led to some modest changes, most notably that residents of the City of Washington were allowed to elect their own mayor, but in Alexandria that did little to quell discontent and after an 1822 debate in the local papers, the Grand Jury again voted for retrocession and a committee to promote it.

But a competing group, led by merchant Phineas Janney, held a meeting shortly thereafter and agreed to draw up a petition against retrocession.

Senator William C. Preston of South Carolina introduced a bill to retrocede the entire District to Maryland and Virginia, to "relieve Congress of the burden of repeated petitions on the subject".

In 1837, when Washington City began to agitate for a territorial government for the District, which would necessitate one set of laws for both counties, the subject of retrocession was again debated in Alexandria and Georgetown.

When the recharter bill failed and the banks were forced to cease operations in July, Alexandria called a town meeting at which they unanimously chose to begin pursuing retrocession.

[30] In early 1846, three years after the Alexandria Canal opened, Alexandria Common Council member Lewis McKenzie, motivated by the large corporation taxes that had to be paid to fund the canal, restarted the retrocession movement when he introduced a motion that the mayor resend the results of the 1840 pro-retrocession vote to Congress and the Virginia legislature.

[32] On February 2, 1846, the Virginia General Assembly suspended their rules to pass unanimously an act accepting the retrocession of Alexandria County if Congress approved.

The bill as proposed would have retained for the district all the land on the south side that was needed for the Long Bridge abutment, but this clause was removed during debate as it was deemed improper.

[53] One argument against retrocession was that the federal government did, in fact, use Alexandria variously as a military outpost, a signal corps site, and a cemetery.

[57] In 1866, Senator Benjamin Wade introduced legislation to repeal retrocession on the grounds that the Civil War proved the necessity of it for defense of the Capital.

[58] In 1902, U.S. Representative James McMillan, chair of the District Committee introduced a resolution to force the Attorney General to bring a lawsuit that would determine the constitutionality of retrocession as he saw restoring Washington, D.C. to its original size as critical to the U.S.

President Taft and members of Congress supported it, citing the need for the District to expand to accommodate the growing government.

By annexing Alexandria in 1846, Virginia arguably breached its contractual obligation to "forever cede and relinquish" the territory for use as the permanent seat of the United States government.

[45] The Supreme Court of the United States never issued a firm opinion on whether the retrocession of the Virginia portion of the District of Columbia was constitutional.

Writing the majority opinion, Justice Noah Haynes Swayne stated only that: The plaintiff in error is estopped from raising the point which he seeks to have decided.

He cannot, under the circumstances, vicariously raise a question, nor force upon the parties to the compact an issue which neither of them desires to make.The United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia had previously ruled that retrocession was constitutional in the 1849 case Sheehy vs. the Bank of the Potomac.

[66] Proposals going back to the 1840s would handle retrocession north of the Potomac similarly to how it was done south of it, with jurisdiction over this area returned to Maryland following approval of Congress, the Maryland legislature and local voters; the difference being that it would carve out a small rump district of land immediately surrounding the United States Capitol, the White House and the Supreme Court building which, in a 2008 bill, would become known as the "National Capital Service Area.

[68] In the 21st century, some members of Congress such as U.S. Representative Dan Lungren,[69] have proposed returning most parts of the city to Maryland in order to grant the residents of the District of Columbia voting representation and control over their local affairs.

[70][71] In the opinion of former Rep. Tom Davis of Virginia, discussing the matter in 1998, retroceding the district to Maryland without that state's consent may require a constitutional amendment.

[citation needed] Opposition by district residents was confirmed in a 2000 George Washington University study when only 21% of those polled supported the option of retrocession.

[78] Then on June 26, 2020, the House voted 232–180 to admit the state of Washington, Douglass Commonwealth, composed of most of the territory of the District of Columbia.