Diver communications

[6] Recreational divers do not usually have access to voice communication equipment, and it does not generally work with a standard scuba demand valve mouthpiece, so they use other signals.

[11] Later, a speaking tube system, patented by Louis Denayrouze in 1874, was tried; this used a second hose with a diaphragm sealing each end to transmit sound,[12] but it was not very successful.

[13] A small number were made by Siebe-Gorman, but the telephone system was introduced soon after this and since it worked better and was safer, the speaking tube was soon obsolete, and most helmets which had them were returned to the factory and converted.

In the early 20th century electrical telephone systems were developed which improved the quality of voice communication.

[11] At first it was only possible for the diver to talk to the surface telephonist, but later double telephone systems were introduced which allowed two-divers to speak directly to each other, while being monitored by the attendant.

Diver telephones were manufactured by Siebe-Gorman, Heinke, Rene Piel, Morse, Eriksson, and Draeger among others.

[11] This system was well-established by the mid-20th century, has been improved several times as new technology became available, and is still in common use for surface-supplied divers using lightweight demand helmets and full-face masks.

By the mid-1980s miniaturized electronics made it possible to use single-sideband modulation, which greatly improved intelligibility in good conditions.

As of 2021, hard wired (cable) voice communications are still the primary method, supported in major commercial applications by one-way closed circuit video but line pull signals are also used as an emergency backup, and through-water voice systems may be used as emergency backup for closed diving bells.

Through-water voice communications do not have the same restriction on diver mobility, which is often the reason for choosing scuba for professional diving, but are more complex, more expensive, and less reliable than the hard-wired systems.

[22] Breath-hold divers use a subset of the recreational diving hand signals where applicable, and have some additional hand-signals specific to freediving.

[24][25] Both hard-wired (cable) and through-water electronic voice communications systems may be used with surface supplied diving.

For commercial diving applications this is a disadvantage, in that the supervisor cannot monitor the condition of the divers by hearing them breathe.

Both the AM and SSB systems require electronic transmitting and receiving equipment worn by the divers, and an immersed transducer connected to the surface unit.

[22] The diver's speech is picked up by the microphone and converted into a high frequency sound signal transmitted to the water by the omnidirectional transducer.

[27] The push-to-talk (PTT) method is the most widely available system for through-water communications, but some equipment allows continuous transmission, or voice activated mode (VOX).

This would run the battery down more rapidly when the background noise level is sufficient to activate transmission, but it allows hands-free communications.

[27] Through-water systems are also used for back-up to the wired communications via the umbilical generally used in closed diving bells.

They operate between a battery powered transducer on the bell and a surface unit using a similar acoustic signal to those used for wireless diver communications.

[29] Divers breathing helium may need a decoder system (also called unscrambling), which reduces the frequency of the sound to make it more intelligible.

The parties take turns to speak, use clear, short sentences, and indicate when they have finished, and whether a response is expected.

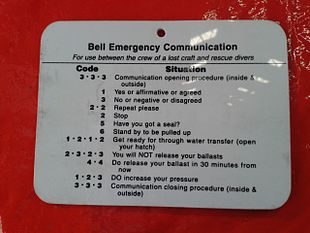

[1] There are emergency signals usually associated with wet and closed bell diving by which the surface and bellman can exchange a limited amount of information which may be critical to the safety of the divers.

They are for use when the voice communications system fails, and provide enough information that the bell can be recovered with minimal risk to the divers.

[17] Tap codes, made by knocking on the hull, are used to communicate with divers trapped in a sealed bell or the occupants of a submersible or submarine during a rescue.

[55] VHF radios and personal emergency locator beacons are available which can transmit a distress signal to nearby vessels and are pressure resistant to recreational diving depths, so they can be carried by a diver and activated at the surface if out of sight of the boat.

[56][58] A vessel supporting a diving operation may be unable to take avoiding action to prevent a collision, as it may be physically connected to divers in the water by lifelines or umbilicals, or may be maneuvering in the close proximity to divers, and is required to indicate this constraint by international maritime law, using the prescribed light and shape signals, and other vessels are obliged to keep clear, both for the safety of the divers, and to prevent collision with the diving support vessel.

[60][62] Divers can carry two differently coloured DSMBs so that they can signal to their surface support for help while decompressing underwater.

This is more likely to be used by commercial, scientific or public service divers to cordon off a work or search area, or an accident or crime scene.

[64] The UDI-28 and UDI-14 wrist mounted decompression computers have a communications feature between wrist units and a surface unit which includes distress signals, a limited set of text messages and a homing signal[65][66][67] In 2022, University of Washington, developed a software app, AquaApp, for mobile devices that repurposes the microphones and speakers on existing smartphones and watches to enable underwater acoustic communication between divers.

[68] The software running on commodity Android smartphones placed in water-proof cases, supports sending one of 240 pre-set messages including SoS beacons and has a range of up to 100 metres.