Dōgen

Originally ordained as a monk in the Tendai School in Kyoto, he was ultimately dissatisfied with its teaching and traveled to China to seek out what he believed to be a more authentic Buddhism.

He remained there for four years, finally training under Tiāntóng Rújìng, an eminent teacher of the Cáodòng lineage of Chinese Chan.

[3] His foster father was his older brother Minamoto no Michitomo, who served in the imperial court as a high-ranking ashō (亞相, "Councillor of State").

[4][3] His mother, named Ishi, the daughter of Matsudono Motofusa and a sister of the monk Ryōkan Hōgen, is said to have died when Dōgen was age 7.

[3] Stating that his mother's death was the reason he wanted to become a monk, Ryōkan sent the young Dōgen to Jien, an abbot at Yokawa on Mount Hiei.

[3] According to the Kenzeiki (建撕記), he became possessed by a single question with regard to the Tendai doctrine: As I study both the exoteric and the esoteric schools of Buddhism, they maintain that human beings are endowed with Dharma-nature by birth.

[8] The Kenzeiki further states that he found no answer to his question at Mount Hiei, and that he was disillusioned by the internal politics and need for social prominence for advancement.

[15] However, tension soon arose as the Tendai community began taking steps to suppress both Zen and Jōdo Shinshū, the new forms of Buddhism in Japan.

[30][31] According to Thomas Kasulis, non-thinking refers to the "pure presence of things as they are", "without affirming nor negating", without accepting nor rejecting, without believing nor disbelieving.

He frequently relegates other Buddhist practices to a lesser status, as he writes in the Bendōwa: "Commitment to Zen is casting off body and mind.

You have no need for incense offerings, homage praying, nembutsu, penance disciplines, or silent sutra readings; just sit single-mindedly.

Indeed, according to Foulk:the specific rituals that seem to be disavowed in the Bendowa passage are all prescribed for Zen monks, often in great detail, in Dogen's other writings.

In Kuyo shobutsu, Dogen recommends the practice of offering incense and making worshipful prostrations before Buddha images and stupas, as prescribed in the sutras and Vinaya texts.

In Raihai tokuzui he urges trainees to revere enlightened teachers and to make offerings and prostrations to them, describing this as a practice which helps pave the way to one's own awakening.

In Chiji shingi he stipulates that the vegetable garden manager in a monastery should participate together with the main body of monks in sutra chanting services (fugin), recitation services (nenju) in which buddhas' names are chanted (a form of nenbutsu practice), and other major ceremonies, and that he should burn incense and make prostrations (shoko raihai) and recite the buddhas' names in prayer morning and evening when at work in the garden.

Finally, in Kankin, Dogen gives detailed directions for sutra reading services (kankin) in which, as he explains, texts could be read either silently or aloud as a means of producing merit to be dedicated to any number of ends, including the satisfaction of wishes made by lay donors, or prayers on behalf of the emperor.

[34] The primary concept underlying Dōgen's Zen practice is "the oneness of practice-verification" or "the unity of cultivation and confirmation" (修證一如 shushō-ittō / shushō-ichinyo).

[38][37][39] The shushō-ittō teaching was first and most famously explained in the Bendōwa (弁道話 A Talk on the Endeavor of the Path, c. 1231) as follows:[37] To think that practice and verification are not one is the view of infidels.

[41] However, Dōgen interpreted the passage differently, rendering it as follows: All are (一 切) sentient beings, (衆生) all things are (悉有) the Buddha-nature (佛性); the Tathagata (如来) abides constantly (常住), is non-existent (無) yet existent (有), and is change (變易).

This view has been developed by scholars such as Steven Heine,[51] Joan Stambaugh[52] and others and has served as a motivation to compare Dōgen's work to that of Martin Heidegger's "Dasein".

[citation needed] Rein Raud has argued that this view is not correct and that Dōgen asserts that all existence is momentary, showing that such a reading would make quite a few of the rather cryptic passages in the Shōbōgenzō quite lucid.

[57] As Döll points out, "It is this second type, as Müller holds, that allows for a positive view of language even from the radically skeptical perspective of Dōgen’s brand of Zen Buddhism.

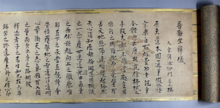

[59] While it was customary for Buddhist works to be written in Chinese, Dōgen often wrote in Japanese, conveying the essence of his thought in a style that was at once concise, compelling, and inspiring.

The Shōbōgenzō served as the basis for the short work entitled Shushō-gi (修證儀), which was compiled in 1890 by a layman named Ouchi Seiran (1845–1918) along with Takiya Takushū (滝谷卓洲) of Eihei-ji and Azegami Baisen (畔上楳仙) of Sōji-ji.

The exact date the book was written is in dispute but Nishijima believes that Dogen may well have begun compiling the koan collection before his trip to China.

The sermons, lectures, sayings and poetry were compiled shortly after Dōgen's death by his main disciples, Koun Ejō (孤雲懐奘, 1198–1280), Senne, and Gien.

[71][72] According to Bodiford, "Monks and laymen recorded these events as testaments to his great mystical power," which "helped confirm the legacy of Dōgen's teachings against competing claims made by members of the Buddhist establishment and other outcast groups."

[68] According to Faure, for Dōgen these auspicious signs were proof that "Eiheiji was the only place in Japan where the Buddhist Dharma was transmitted correctly and that this monastery was thus rivaled by no other.

[75] This story is repeated in official works sponsored by the Sōtō Shū Head Office[71][75] and there is even a sculpture of the event in a water treatment pond in Eihei-ji Temple.

At Eihei-ji a divine dragon showed up requesting the eight Precepts of abstinence and asking to be included among the daily transfers of merit.