Donkeys in France

Historically, donkeys were primarily employed as pack and draught animals for modest farmers, and until the mid-20th century, they were essential for any job requiring the transport of goods.

Donkeys have left a significant imprint on French culture, featuring prominently in proverbs, popular songs, games, tales, legends, and novels.

Despite the frequent portrayal of donkeys in proverbs as foolish creatures, traditional beliefs often depict them as pious and virtuous animals, as well as symbols of wealth.

[10] These sources also mention trials for bestiality, such as an ass-driver from Villeneuve-l'Archevêque (Champagne) who was condemned on January 8, 1558, to be hanged and then burned with his donkey for having sexual relations with it.

This practice possibly originated from ancient Greek traditions that sought to highlight the ridiculous and highly sexualized aspects associated with the donkey.

[12][13] British historian Martin Ingram, in a study of historical social control mechanisms in Europe, notes that the "asouade", which was organized during the French charivari, was a form of punishment for women who beat their husbands.

[16] While it is challenging to ascertain the precise number of French donkeys in the 19th century, the pervasiveness of cultural production referencing them is evidence of their prominent presence in society at the time.

[19] Historically, the donkey was utilized for agricultural purposes, particularly in the transportation of heavy loads such as milk cans in Normandy and young lambs in Provence.

[21] The emergence of novel applications for donkeys has prompted inquiries within the social sciences regarding the evolving relationship between these animals and the rupture they represent with past uses.

[59] In France, the dairy industry is well-developed, producing and selling a variety of products, including donkey milk soap and various cosmetic and medicinal goods.

[51] In 1996, the "Parc du Fou de l'ne" was established in Amboise,[67][68] showcasing fourteen donkey breeds on a four-hectare site with educational exhibits.

[82] In 2018, a study by Michel Lompech and colleagues utilized cross-referenced data sources to conclude that donkeys are notably prevalent in the French department of Manche, which boasts the largest herd with 1,100 heads.

The Poitou donkey is associated with mule production, while the Grand Noir du Berry was selected for field, vineyard, and barge traction.

[90] Michel Pastoureau notes that, since Antiquity, donkeys have been symbolically associated with a range of negative traits, including folly, ignorance, stubbornness, laziness, lewdness, and the opposite of these, humility, sobriety, and patience.

[104] Michel Pastoureau observes that in both Latin and the vernacular languages that succeeded it, numerous proverbs, puns, expressions, and insults highlight the foolishness and stubbornness of the donkey, originating from antiquity and still in use in the 21st century.

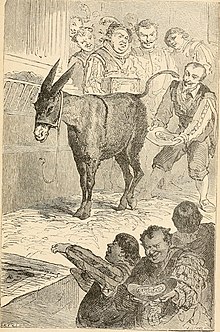

[105] At the time, it was common practice in France to punish students who were perceived to be lazy by forcing them to wear a dunce cap and threatening that they would grow donkey ears if they did not work harder.

"[108] René Volot notes that the donkey is associated with the scapegoat and the fool who believes the moon has fallen into the water upon seeing its reflection, both in a pedagogical text by Claude Augé and in a Cévenol tale.

[109] In 1876, Charles-Alexandre Perron included two proverbs from Franche-Comté in his compilation of French proverbs: Quand le foin manque au râtelier, les ânes se battent (When hay is lacking in the manger, the donkeys fight),[110] and Un âne court au chardon et laisse la bonne herbe (A donkey runs to the thistle and leaves the good grass).

[111] The 1932-1935 edition of the French Academy Dictionary cites the proverb: À laver la tête d'un More, à laver la tête d'un âne, on perd sa lessive, which can be translated as "one takes great pains in vain to make a man understand something beyond his reach or to correct an incorrigible man.

[105] Michel Pastoureau notes that Buridan's donkey paradox, which dies of hunger and thirst between a bucket of water and a bucket of food due to indecision, gave rise to the proverbial expression être comme l'âne de Buridan (To sit on the fence), though "it would be absurd to believe that, placed in such a situation, an animal or a human being could let themselves die of hunger or thirst.

[118] In 1853, Pierre-Alexandre Gratet-Duplessis, a bibliophile, cited the saying Amour apprend les ânes à danser (Love makes donkeys able to dance) in La Fleur des proverbes français.

[136] Several French traditions emphasize that its back is marked with a cross, which is interpreted as a sign given in reward for the services it rendered to the Savior, protecting it from the Devil.

[140] He also notes a tradition, long since fallen into disuse by the late 19th century, that allowed donkeys to enter churches and recite ceremonial prose in their honor.

A gray donkey appeared in Vaudricourt's square during Midnight Mass and permitted children fleeing the church to ride on its back, extending its body to accommodate twenty of them.

Since that time, the creature reappears every Christmas night, bearing the souls of the damned, traversing the village, returning to its starting point at midnight, and entering the aforementioned pond from which it emerged.

[143] Pierre Dubois references a similar account in La Grande Encyclopédie des fées, wherein the creature is described as a "magnificent white horse" that drowns its young riders in a bottomless pond.

[154] Chambry highlights the enduring presence of the donkey in literary representations, dating back to the earliest translated texts in antiquity (the Bible, Aesop's fables, etc.)

[157] The donkey also features Les Contes du chat perché (1934-1946) by Marcel Aymé, a collection of short stories set on a traditional farm.

[174] Claude Seignolle notes the statue of L'âne qui vielle, on the western door of Chartres Cathedral (a donkey standing on its hind legs playing the hurdy-gurdy or harp), as being as famous as the Manneken-Pis in Brussels.

[176][177] The canvas elicited diverse responses from art enthusiasts until Roland Dorgelès revealed that the painting was created by Lolo, the donkey belonging to the proprietor of the cabaret Au Lapin Agile, with a brush attached to its tail.