Doric order

Originating in the western Doric region of Greece, it is the earliest and, in its essence, the simplest of the orders, though still with complex details in the entablature above.

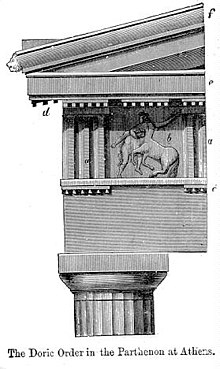

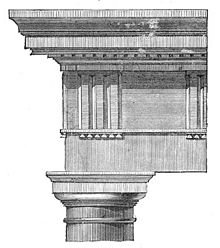

The Greek Doric column was fluted,[1] and had no base, dropping straight into the stylobate or platform on which the temple or other building stood.

The capital was a simple circular form, with some mouldings, under a square cushion that is very wide in early versions, but later more restrained.

The relatively uncommon Roman and Renaissance Doric retained these, and often introduced thin layers of moulding or further ornament, as well as often using plain columns.

More often they used versions of the Tuscan order, elaborated for nationalistic reasons by Italian Renaissance writers, which is in effect a simplified Doric, with un-fluted columns and a simpler entablature with no triglyphs or guttae.

The ancient architect and architectural historian Vitruvius associates the Doric with masculine proportions (the Ionic representing the feminine).

[5] In their original Greek version, Doric columns stood directly on the flat pavement (the stylobate) of a temple without a base.

With a height only four to eight times their diameter, the columns were the most squat of all the classical orders; their vertical shafts were fluted with 20 parallel concave grooves, each rising to a sharp edge called an arris.

They were topped by a smooth capital that flared from the column to meet a square abacus at the intersection with the horizontal beam (architrave) that they carried.

It was most popular in the Archaic Period (750–480 BC) in mainland Greece, and also found in Magna Graecia (southern Italy), as in the three temples at Paestum.

Under each triglyph are peglike "stagons" or "guttae" (literally: drops) that appear as if they were hammered in from below to stabilize the post-and-beam (trabeated) construction.

[10] Other examples of the Doric order include the three 6th-century BC temples at Paestum in southern Italy, a region called Magna Graecia, which was settled by Greek colonists.

The recessed "necking" in the nature of fluting at the top of the shafts and the wide cushionlike echinus may be interpreted as slightly self-conscious archaising features, for Delos is Apollo's ancient birthplace.

The detail, part of the basic vocabulary of trained architects from the later 18th century onwards, shows how the width of the metopes was flexible: here they bear the famous sculptures including the battle of Lapiths and Centaurs.

The architrave corner needed to be left "blank", which is sometimes referred to as a half, or demi-, metope (illustration, V., in Spacing the Columns above).

The most influential, and perhaps the earliest, use of the Doric in Renaissance architecture was in the circular Tempietto by Donato Bramante (1502 or later), in the courtyard of San Pietro in Montorio, Rome.

Its appearance in the new phase of Classicism brought with it new connotations of high-minded primitive simplicity, seriousness of purpose, noble sobriety.

The revived Doric did not return to Sicily until 1789, when a French architect researching the ancient Greek temples designed an entrance to the Botanical Gardens in Palermo.