Dorothy Hewett

[3] Her business acumen made the family wealthy, first in a drapery shop in Perth, then in the wheat belt through farm production, ownership of three local general stores, insider trading in land options along the line of a new railway, and liens on crops and property.

Hewett attended Perth College, where she had to wear shoes, hat and gloves for the first time, a shock after her ragamuffin life on the farm.

[12] With several friends she founded the University Drama Society and acted in a number of Repertory plays, including a melodrama that she wrote herself.

[10] After leaving UWA, Hewett worked in a bookshop and as a cadet journalist with the Perth Daily News, but lost both these jobs.

[15] Recuperating after an attempted suicide[a] following a failed wartime relationship, she wrote the poem Testament, her first mature work, which won the prestigious ABC Poetry Prize in 1945.

Hewett covered the 1946 Pilbara Strike for the Worker's Star,[21] and wrote the epic ballad, Clancy and Dooley and Don McLeod,[22] which cemented her position as a radical author and a supporter of Indigenous rights.

The CPA strongly disapproved of what they called immoral behaviour and she had to restart at the bottom, selling the Communist weekly paper Tribune on the street, and leafleting.

[23] In the period of McCarthyism their house was a regular meeting place for the CPA, devoted to printing and distributing material opposing the Communist Party Dissolution referendum and later the Petrov Commission.

[24] The following year her first child, Clancy, died of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Melbourne, an event which was to have a profound effect on the rest of her life.

[25][b] In 1952, Hewett and Flood joined a trade union delegation to Russia, and they were among the first Westerners to visit the new People's Republic of China.

Hewett took a job as a copywriter on the catalogue of Walton Sears Department Store to support the family, and then with Leyden Publishing.

Weevils in the Flour, a song about the Depression childhood of her friend Vera Deacon,[35] has been a favourite with union choirs and folk singers, with a folklore all of its own.

[37] Les Flood had been sighted in WA, and to avoid him, the family remained in Queensland for a year and bought an old house in Wynnum, Brisbane.

[3] During 1962, the family participated in the radical salon society along the Brisbane foreshore, led by John Manifold the folklorist and poet.

[40] As they made the long return journey to Perth on the Trans Australian Railway at the end of the year, Hewett went into labour with her sixth child and the baby Rozanna was delivered in Kalgoorlie.

It caricatured members of the UWA English department, so the play was unable to be staged in Perth for fear of defamation proceedings,[48] and it was first performed at the PACT Theatre in Sydney in May 1969.

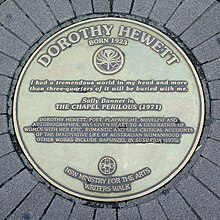

The self-parodying hero, Sally Banner, resonated with the emerging feminist movement and ensured Hewett's lasting fame.

[19] She returned in late 1973 to her "city of marvellous experience" Sydney,[19] where she bought a rambling terrace in Woollahra with her share of her recently deceased mother's estate.

Here she enjoyed her most productive years, creating in quick succession: The Tatty Hollow Story (a woman who cannot be defined by her former lovers); The Golden Oldies (for two actors and two dummies); the opera extravaganza Joan (her only work set outside of Australia, with 75 actors and 40 musicians); the show musical Pandora's Cross; the rock opera Catspaw; The Fields of Heaven for the Festival of Perth; and two books of poetry Rapunzel in Suburbia and Greenhouse.

[51] In collaboration with poets associated with the "Generation of '68"[52] and New Poetry magazine,[53] particularly Robert Adamson (with whom she maintained a close lifetime friendship), her work became more sparse and directed and the romantic element more controlled.

[57] According to The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature, Hewett used "poetry, music and symbol to portray life's paradoxes and her characters' mingling of perception and delusion" while adding "her verse is confessional and romantic in theme, wryly humorous, frankly bawdy, varied in tone and rich in imagery".

[58] D'Aeth finds a "dizzying amplitude of styles in her work, beginning with modernism in her early poems through socialist realism to expressionist musical farce, followed by a late response to American poetic experimentation in the 1950s and 1960s", citing her trademark "vivid phantasmagoria and baroque larrikin humour".

Even a single play like The Chapel Perilous employs tragedy, farce, naturalism, Brechtian expressionism and musical comedy in quick succession.

She only became a full-time writer from the age of 51, with the aid of Literature Board grants, intermittent earnings from writing and from university fellowships, and an ongoing bequest from her father's estate.

Mixed reviews and modest box office takings caused the hyped musical Pandora's Cross to shoulder part of the blame for the failure of the new Paris Theatre company in 1978.

[51] Several fundraising events[71] opposing censorship were held to help defray the legal defence costs,[72] and Bob Hudson recorded a satirical song "Libel" to assist.

The plays The Chapel Perilous and The Tatty Hollow Story, which contained unflattering depictions of a Davies-like character, could not be shown in Perth.

In 2000 Hewett launched a broadside at lack of support for writers by publishing houses and governments, saying independent publishing houses were being taken over by big overseas companies, that the price of books was rising, and only generous public funding would enable experimental writing and young, unknown writers to find a place.

[77] Some of their sexual activity had been conducted with adult visitors to Woollahra, specifically naming the political writer Bob Ellis, Martin Sharp and other deceased celebrities.

A media frenzy ensued, in which the tabloid press attacked "paedophile rings", the libertarian 1970s, Hewett's lapsed Communism, and Ellis in particular, who was detested by conservatives.