John Clarke (Baptist minister)

John Clarke (October 1609 – 20 April 1676) was a physician, politician, and Baptist minister, who was co-founder of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, author of its influential charter, and a leading advocate of religious freedom in America.

Clarke returned to Rhode Island following his success at procuring the charter; he became very active in civil affairs there, and continued to pastor his church in Newport until his death in 1676.

[1][2] Clarke was apparently highly educated, judging from the fact that he arrived in New England at the age of 28 qualified as both a physician and a Baptist minister.

John Clarke apparently went with both groups, based on what he wrote in his book: "By reason of the suffocating heat of the summer before [1637], I went to the North to be somewhat cooler, but the winter following [1637–38] proved so cold, that we were forced in the spring to make towards the South.

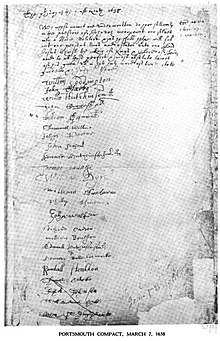

[9] 23 men signed the document which was intended to form a "Bodie Politick" based on Christian principles, and Coddington was chosen as the leader of the group.

Williams was uncertain about English claims to these lands, so Clarke led a delegation of three men to Plymouth Colony where he was informed that Sowams was under their jurisdiction but Aquidneck Island was not.

[17] Clarke had some legal training, and historian Albert Henry Newman argued that he was the principal author of the first complete code of laws that was enacted by the fledgling colony in 1647.

[18][19] Rhode Island historian and Lieutenant Governor Samuel G. Arnold extolled the virtues of this code, calling it a model of legislation which has not been surpassed.

He wanted to connect with his Baptist faith, but he was too infirm to travel to Newport, so Clarke, Obadiah Holmes, and John Crandall visited him at his home.

Clarke responded to this by writing a letter to the court from prison the following day, accepting the implied challenge to have a debate with the Puritan ministers on religious beliefs and practices.

[28][31][44] Much later, Rhode Island Governor Joseph Jenckes wrote, "Those who have seen the scars on Mr. Holmes' back (which the old man was wont to call the marks of the Lord Jesus), have expressed a wonder that he should live.

"[45] Following the men's arrest and ill treatment, Sir Richard Saltonstall wrote from England to Reverends Cotton and Wilson of the Boston church: "These rigid wayes have lay'd you very lowe in the hearts of the saynts.

"[46] Shortly after the incident, Roger Williams wrote a letter to Governor Endicott, making an earnest plea for toleration in matters of conscience and religion, but the request was unheeded.

[48] Some scholars have argued that Clarke's mission trip was planned to provoke the Massachusetts officials in order to support the cause of Rhode Island in England.

The book was an appeal to the English government outlining the case for religious tolerance, and it was instrumental in shaping public opinion and generating support for a charter for the Rhode Island colony.

Simultaneously, the mainland towns of Providence and Warwick sent Roger Williams on a similar errand, and the three men sailed for England in November 1651, just a few months after Clarke had been released from prison.

The book begins with a letter to the English Parliament and Council of State, conveying an earnest plea for liberty of conscience and religious toleration.

The Massachusetts authorities became so alarmed over the contents of Ill Newes that Thomas Cobbet, the minister of the Lynn church, wrote a rebuttal entitled The Civil Magistrates Power in Matters of Religion Modestly Debated (1653).

One of his means of support was preaching at this church, which he called his "cheefe place for proffitt and preference", possibly because this arrangement offered him room and board.

[60] In 1660, Charles II ascended the throne of England, and within two years the Act of Uniformity was passed requiring unified religious observances centered on the Anglican Church.

The new king harbored prejudices against the Presbyterians, Independents, and Baptists, increasing Clarke's difficulty in crafting a charter that included religious freedoms.

His earnest request was "TO HOLD FORTH A LIVELY EXPERIMENT THAT A MOST FLOURISHING CIVILL STATE MAY STAND ... AND BEST BE MAINTAYNED ... WITH A FULL LIBERTIE IN RELIGIOUS CONCERNMENTS".

[69] In this charter, colonial boundaries were outlined, provisions for a military and for prosecuting war were effected, fishing privileges were secured, and a means of appeal to England was detailed.

Only a week after the king put his seal on the charter, Clarke made an indenture with Richard Deane of London, mortgaging his Newport properties to raise money.

One of the commissioners was Samuel Maverick, a good friend of Rhode Island's recent governor William Brenton, who abhorred the Atherton Company.

[79][80] From 1675 to 1676, Rhode Island became embroiled in King Philip's War, considered "the most disastrous conflict to ever devastate New England," and leaving the mainland towns of the colony in ruins.

Though Rhode Island was much more at peace with the Indians than the other colonies, because of geography, it took the brunt of damage from the conflict, and the settlements of Warwick and Pawtuxet were totally destroyed, with much of Providence ruined as well.

[90] Historian Louis Asher wrote, "It hardly seems arguable that Dr. Clarke was the first one to bring democracy to the New World by means of Rhode Island.

"[91] Bicknell also asserted that Clarke was the "recognized founder and father of the Aquidneck Plantations, the author of the Compact of Portsmouth and leading spirit in the organization and administration of the island towns.

Also Four Proposals to the Honoured Parliament and Councel of State, Touching the Way to Propagate the Gospel of Christ (with Small Charge and Great Safety) Both in Old England and New.