Dreamtime (book)

Dreamtime: Concerning the Boundary between Wilderness and Civilization is an anthropological and philosophical study of the altered states of consciousness found in shamanism and European witchcraft written by German anthropologist Hans Peter Duerr.

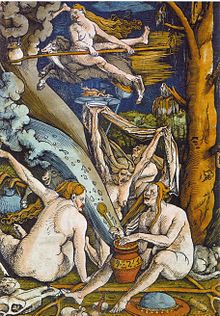

Dreamtime opens with the premise that many of those accused of witchcraft in early modern Christendom had been undergoing visionary journeys with the aid of a hallucinogenic salve which was suppressed by the Christian authorities.

He argues that "archaic cultures" recognize that a human can only truly understand themselves if they go to the mental boundary between "civilization" and "wilderness", and that it is this altered state of consciousness which both the shaman and the European witch reached in their visionary journeys.

Dreamtime was a controversial best-seller upon its initial release in West Germany, and inspired academic debate leading to the publication of Der Gläserne Zaun (1983), an anthology discussing Duerr's ideas, edited by Rolf Gehlen and Bernd Wolf.

He had spent the day visiting the Puye Cliff Dwellings and was returning to the Albuquerque Greyhound Bus Station, where he met a Tewa Native yerbatero (herbalist) buying a cup of coffee, and struck up a conversation.

Duerr asked the yerbatero if he could help him find a Native family living in one of the pueblos north of Santa Fe with whom he could stay, to conduct anthropological research into the nightly dances that took place in the subterranean kivas.

After a period of intellectual stagnation during the preceding decades, the 1970s saw the rising popularity of the discipline, with a dramatic increase in the number of students enrolling to study ethnography at West German universities.

This increase in philosophical discussion within German anthropology was largely rejected by the "official academic representatives" of the discipline, who believed that it exceeded the "limits of scientific respectability", but it was nonetheless adopted by Duerr in Dreamtime.

[3] "Dreamtime served as a charter for a generation which found society repressive and which sought to escape it by a) physically leaving it, b) cultivating a higher consciousness which could transcend it, or c) getting so stoned that one either did not notice what was bad or else was not troubled by it.

[4][5][6] According to the American Indologist Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty, Dreamtime became "the canon of a cult for intellectual former hippies", dealing as it did with issues such as "drugs, sex, anarchy, [and] lurid religions".

Similarly, the witches of the early modern period also left the everyday world, and like the shamans of Siberia experienced their "wild" or "animal aspect" in order to understand their human side.

Duerr argues that the conversations between the animal and the individual undertaking the vision are neither literal nor delusional, but that the only way to understand this is to situate oneself "on the fence", between the worlds of civilisation and wilderness.

[23] Writing in The Journal of Religion, Gail Hinich claimed that Duerr's Dreamtime had a "maverick whimsy and passion" that stemmed from its argument that Western society had unfairly forced the "otherworld" into "an autistic tyranny of the self".

[6] "The book remains a groundbreaking ethnographic study that ranges from old Norse sagas to aboriginal initiation rites, from the life of Jesus to fertility-cult practices, shamanism to politics, ethnopharmacology to psychopathology, comparative religion to philosophy of science, witches to werewolves and back again."

He ultimately felt that because Duerr had refused to correct his factual mistakes for the English translation, the book had left the realms of scholarship and instead become an "obscure cultural artifact", one which was "represented by the myriad descriptions of cryptic symbols" that are discussed within its pages.

"[25] In the Comparative Civilizations Review journal, Anthony M. Stevens-Arroyo proclaimed that it was easy "to get lost" in Dreamtime, believing that the multitude of ethnographic and historical facts presented by Duerr often distracted from the book's main arguments.

He also remarked that Duerr "practices what he preaches", noting that the book was something of an apologia for his involvement in the counter-cultural and drug subcultures of the 1960s and his continuing advocacy of the use of mind-altering substances, in the same style as Timothy Leary.

Considering the work to be an attack on social convention, he believes that Duerr has made use of mind-altering drugs to cross boundaries into altered states of consciousness and that Dreamtime is his invitation for others to join him.

[26] In a commentary piece for the Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford, Charles Stewart expressed his opinion that Dreamtime is best described as "the sort of book that Carlos Castaneda might have written if he were a German philosopher."

[5] Ultimately, Doniger O'Flaherty was critical of Dreamtime, commenting that "Duerr is attempting to hunt with the hounds and run with the hare, and his book is likely to infuriate both ordinary readers and scholars."

Atchity maintains that Dreamtime offers nothing new except "the energy of its serendipity", noting similarities with books such as James Frazer's The Golden Bough (1890), Robert Graves' The White Goddess (1948), and the works of Carlos Castenada.

[33] Duerr had briefly discussed the case in the chapter "Wild Women and Werewolves", in which he compared it with various European folk traditions in which individuals broke social taboos and made mischief in public, arguing that they represented a battle between the forces of chaos and order.