Drosera

[2] These members of the family Droseraceae[1] lure, capture, and digest insects using stalked mucilaginous glands covering their leaf surfaces.

The Principia Botanica, published in 1787, states “Sun-dew (Drosera) derives its name from small drops of a liquor-like dew, hanging on its fringed leaves, and continuing in the hottest part of the day, exposed to the sun.”[9] The unrooted cladogram to the right shows the relationship between various subgenera and classes as defined by the analysis of Rivadavia et al.[10] The monotypic section Meristocaulis was not included in the study, so its place in this system is unclear.

[15] A further type of (mostly strong red and yellow) leaf coloration has recently been discovered in a few Australian species (D. hartmeyerorum, D. indica).

The radially symmetrical (actinomorphic) flowers are always perfect and have five parts (the exceptions to this rule are the four-petaled D. pygmaea and the eight to 12-petaled D. heterophylla).

Australian species display a wider range of colors, including orange (D. callistos), red (D. adelae), yellow (D. zigzagia) or metallic violet (D. microphylla).

[21] They are relatively useless for nutrient uptake, and they serve mainly to absorb water and to anchor the plant to the ground; they have long hairs.

Some Australian species form underground corms for this purpose, which also serve to allow the plants to survive dry summers.

Seeds of the tuberous species require a hot, dry summer period followed by a cool, moist winter to germinate.

Vegetative reproduction occurs naturally in some species that produce stolons or when roots come close to the surface of the soil.

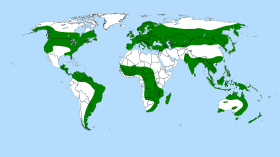

Contrary to previous supposition, the evolutionary speciation of this genus is no longer thought to have occurred with the breakup of Gondwana through continental drift.

In addition to the three species and the hybrid native to Europe, North America is also home to four additional species; D. brevifolia is a small annual native to coastal states from Texas to Virginia, while D. capillaris, a slightly larger plant with a similar range, is also found in areas of the Caribbean.

The botanist Ludwig Diels, author of the only monograph of the family to date, called this description an "arrant misjudgment of this genus' highly unusual distributional circumstances (arge Verkennung ihrer höchst eigentümlichen Verbreitungsverhältnisse)", while admitting sundew species do "occupy a significant part of the Earth's surface (einen beträchtlichen Teil der Erdoberfläche besetzt)".

[24] Sundews generally grow in seasonally moist or more rarely constantly wet habitats with acidic soils and high levels of sunlight.

Common habitats include bogs, fens, swamps, marshes, the tepuis of Venezuela, the wallums of coastal Australia, the fynbos of South Africa, and moist streambanks.

The temperate species, which form hibernacula in the winter, are examples of such adaptation to habitats; in general, sundews tend to inhabit warm climates, and are only moderately frost-resistant.

[26] Drosera species are protected by law in many European countries, such as Germany, Austria, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, France, and Bulgaria.

Reintroduction of plants into such habitats is usually difficult or impossible, as the ecological needs of certain populations are closely tied to their geographical location.

[30] Increased legal protection of bogs and moors,[34] and a concentrated effort to renaturalize such habitats, are possible ways to combat threats to Drosera plants' survival.

[36][37] In South Africa and Australia, two of the three centers of species diversity, the natural habitats of these plants are undergoing a high degree of pressure from human activities.

[39] Culbreth's 1927 Materia Medica listed D. rotundifolia, D. anglica and D. linearis as being used as stimulants and expectorants, and "of doubtful efficacy" for treating bronchitis, whooping cough, and tuberculosis.

[41] The French Pharmacopoeia of 1965 listed sundew for the treatment of inflammatory diseases such as asthma, chronic bronchitis and whooping cough.

[43] In traditional medicine practices, Drosera is used to treat ailments such as asthma, coughs, lung infections, and stomach ulcers.

[48] Because of their carnivorous nature and the beauty of their glistening traps, sundews have become favorite ornamental plants; however, the environmental requirements of most species are relatively stringent and can be difficult to meet in cultivation.

In general, though, sundews require high environmental moisture content, usually in the form of a constantly moist or wet soil substrate.

Most species also require this water to be pure, as nutrients, salts, or minerals in their soil can stunt their growth or even kill them.

[15] The mucilage produced by Drosera has remarkable elastic properties and has made this genus a very attractive subject in biomaterials research.

In one recent study, the adhesive mucilages of three species (D. binata, D. capensis, and D. spatulata) were analyzed for nanofiber and nanoparticle content.

More importantly for biomaterials research, however, is the fact that, when dried, the mucin provides a suitable substrate for the attachment of living cells.

Essentially, a coating of Drosera mucilage on a surgical implant, such as a replacement hip or an organ transplant, could drastically improve the rate of recovery and decrease the potential for rejection, because living tissue can effectively attach and grow on it.

The authors also suggest a wide variety of applications for Drosera mucin, including wound treatment, regenerative medicine, or enhancing synthetic adhesives.