Wet market

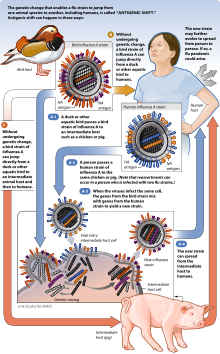

[27] Most wet markets do not trade in wild or exotic animals,[32] but some that do have been linked to outbreaks of zoonotic diseases including COVID-19, H5N1 avian flu, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and monkeypox.

[1][11] Wet markets can be categorized according to their ownership structure (privately owned, state-owned, or community-owned), scale (wholesale or retail), and produce (fruits, vegetables, slaughtered meat, or live animals).

[1][49][50] Wet markets are less dependent on imported goods than supermarkets due to their smaller volumes and lesser emphasis on consistency.

[58] Due to unhygienic sanitation standards and the connection to the spread of zoonoses and pandemics, critics have grouped live animal markets together with factory farming as major health hazards in China and across the world.

[63][64][65][66] In March and April 2020, some reports have said that wildlife markets in Asia,[67][68][69] Africa,[70][71][72] and in general all over the world are prone to health risks.

[73] Due to the suspicions that wet markets could have played a role in the emergence of COVID-19, a group of US lawmakers, NIAID director Anthony Fauci, UNEP biodiversity chief Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, and CBCGDF secretary general Zhou Jinfeng called in April 2020 for the global closure of wildlife markets due to the potential for zoonotic diseases and risk to endangered species.

[74][75][76][77] In April 2021, the World Health Organization called for a total ban on the sale of live animals in food markets in order to prevent future pandemics.

[79][80][81] These include proposals for "standardised global monitoring of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions", which the World Health Organization announced in April 2020 that it was developing as requirements for wet markets to open.

[82] During the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Chinese wet markets were heavily criticized in media outlets as a potential source for the virus.

[11][25][38][39][84] There are wet markets throughout the world, with the largest concentration in Asia followed by Europe and North America according to touristic social network data in 2019.

[85] According to a 2013 study on agricultural value chains, approximately 90% of households in Ethiopia across all income groups purchase their beef through local butchers in wet markets.

[88] According to a 2011 USDA Foreign Agricultural Service report, most of the clientele of traditional open-air wet markets in Nigeria are low and middle income consumers.

[90][92] In its place, the local government opened the Ibadan Central Abattoir in Amosun Village, Akinyele through public-private partnerships.

[90][92] The new facility is equipped with modern facilities for slaughter and processing of meat were provided in 2014 through public-private partnerships and is one of the largest abattoirs in West Africa, consisting of 15 hectares of land with stalls for 1000 meat sellers, 170 shops, administrative building, clinic, canteen, cold room, and an incinerator.

[96] According to a 2010 USDA Foreign Agricultural Service report, each small town in Colombia typically has a wet market that is supplied by local production and opens at least once a week.

[101] A 2002 study observed a trend that Mexican consumers, especially those in the middle class, increasingly prefer supermarkets for beef purchases as opposed to traditional wet markets.

[102][103] In 2014, a study of Mexican beef retail also noted an ongoing transition from traditional full-service wet markets to self-service meat display cases in supermarkets.

[45] Since the 1990s, large cities across China have moved traditional outdoor wet markets to modern indoor facilities.

[47][1] As of 2018, wet markets remained the most prevalent food outlet in urban regions of China despite the rise of supermarket chains since the 1990s.

[20][16][108] The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan was linked to the origin of COVID-19 due to its early cluster of cases,[109][58] leading to further restrictions and enforcement in 2020.

[121] Delhi wet markets generally consist of a number of small retailers that cluster together to sell their produce during daily fixed hours.

[5] In 2016, the Indonesia government's policy to stabilise beef prices required importers to sell cheaper-priced meats in wet markets instead of in supermarkets and hypermarkets.

[129] In March 2020, the Pasig local government launched a mobile wet market to ensure access to basic goods during the COVID-19 pandemic.

[132] In early 2020, the National Environment Agency issued advisories for "high standards of hygiene and cleanliness" for the 83 markets that it oversees in a response to the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.

[133] Many wet markets in Taiwan originated as groups of peddlers and roadside stalls that organized into informal physical structures.

[134] The new facilities provided better hygiene, disability accessibility, and refrigeration, but the relocation was initially met with hesitation from the local vendors before a grassroots outreach campaign led to greater acceptance.

[49] In October 2018, a Meat & Livestock Australia report said that while the United Arab Emirates's grocery retail sector is highly developed, wet markets are still prominent throughout the country.

[122] In 2017, there were approximately 9,000 wet markets, 800 supermarkets, 160 shopping malls and 1.3 million small family-owned stores across Vietnam according to government estimates.

[148][149] The last stalls closed in the 1990s and the building is still derelict as of 2018 despite failed attempts to redevelop the site into a new food market complex.

[148][149][147] In 2020, SBS reported that wet markets were once common in Australia and were gradually shut down over time as abattoirs were centralised and moved away from cities.