IPv6

IPv6 was developed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) to deal with the long-anticipated problem of IPv4 address exhaustion, and was intended to replace IPv4.

The actual number is slightly smaller, as multiple ranges are reserved for special usage or completely excluded from general use.

The addressing architecture of IPv6 is defined in RFC 4291 and allows three different types of transmission: unicast, anycast and multicast.

These addresses are typically displayed in dot-decimal notation as decimal values of four octets, each in the range 0 to 255, or 8 bits per number.

Address exhaustion was not initially a concern in IPv4 as this version was originally presumed to be a test of DARPA's networking concepts.

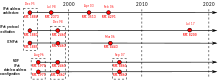

[9][10][11] This leaves African Network Information Center (AFRINIC) as the sole regional internet registry that is still using the normal protocol for distributing IPv4 addresses.

[12] RIPE NCC announced that it had fully run out of IPv4 addresses on 25 November 2019,[13] and called for greater progress on the adoption of IPv6.

Multicasting, the transmission of a packet to multiple destinations in a single send operation, is part of the base specification in IPv6.

[16] In IPv4 it is very difficult for an organization to get even one globally routable multicast group assignment, and the implementation of inter-domain solutions is arcane.

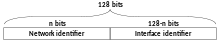

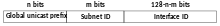

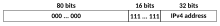

[17] Unicast address assignments by a local Internet registry for IPv6 have at least a 64-bit routing prefix, yielding the smallest subnet size available in IPv6 (also 64 bits).

Temporary addresses are used by default by Windows since XP SP1,[23] macOS since (Mac OS X) 10.7, Android since 4.0, and iOS since version 4.3.

[2][14] However, many devices implement IPv6 support in software (as opposed to hardware), thus resulting in very bad packet processing performance.

[30] Additionally, for many implementations, the use of Extension Headers causes packets to be processed by a router's CPU, leading to poor performance or even security issues.

The absence of a checksum in the IPv6 header furthers the end-to-end principle of Internet design, which envisioned that most processing in the network occurs in the leaf nodes.

[2] However, RFC 7872 notes that some network operators drop IPv6 packets with extension headers when they traverse transit autonomous systems.

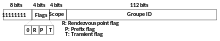

The header consists of a fixed portion with minimal functionality required for all packets and may be followed by optional extensions to implement special features.

It contains the source and destination addresses, traffic class, hop count, and the type of the optional extension or payload which follows the header.

[35] Extension headers carry options that are used for special treatment of a packet in the network, e.g., for routing, fragmentation, and for security using the IPsec framework.

Hosts are expected to use Path MTU Discovery to make their packets small enough to reach the destination without needing to be fragmented.

The host can compute and assign the Interface identifier by itself without the presence or cooperation of an external network component like a DHCP server, in a process called link-local address autoconfiguration.

Once a unique link-local address is established, the IPv6 host determines whether the LAN is connected on this link to any router interface that supports IPv6.

[49] In the Domain Name System (DNS), hostnames are mapped to IPv6 addresses by AAAA ("quad-A") resource records.

For reverse resolution, the IETF reserved the domain ip6.arpa, where the name space is hierarchically divided by the 1-digit hexadecimal representation of nibble units (4 bits) of the IPv6 address.

This includes many of the world's major ISPs and mobile network operators, such as Verizon Wireless, StarHub Cable, Chubu Telecommunications, Kabel Deutschland, Swisscom, T-Mobile, Internode and Telefónica.

A 2017 survey found that many DSL customers that were served by a dual stack ISP did not request DNS servers to resolve fully qualified domain names into IPv6 addresses.

It was expected that 6to4 and Teredo would be widely deployed until ISP networks would switch to native IPv6, but by 2014 Google Statistics showed that the use of both mechanisms had dropped to almost 0.

[5]: 209 By the beginning of 1992, several proposals appeared for an expanded Internet addressing system and by the end of 1992 the IETF announced a call for white papers.

[71] In September 1993, the IETF created a temporary, ad hoc IP Next Generation (IPng) area to deal specifically with such issues.

The new area was led by Allison Mankin and Scott Bradner, and had a directorate with 15 engineers from diverse backgrounds for direction-setting and preliminary document review:[7][72] The working-group members were J. Allard (Microsoft), Steve Bellovin (AT&T), Jim Bound (Digital Equipment Corporation), Ross Callon (Wellfleet), Brian Carpenter (CERN), Dave Clark (MIT), John Curran (NEARNET), Steve Deering (Xerox), Dino Farinacci (Cisco), Paul Francis (NTT), Eric Fleischmann (Boeing), Mark Knopper (Ameritech), Greg Minshall (Novell), Rob Ullmann (Lotus), and Lixia Zhang (Xerox).

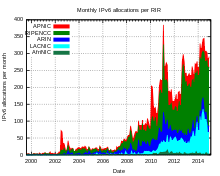

Internet backbone transit networks offering IPv6 support existed in every country globally, except in parts of Africa, the Middle East and China.