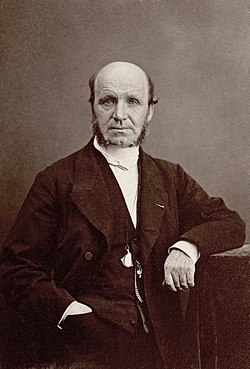

Guillaume Duchenne de Boulogne

The era of modern neurology developed from Duchenne's understanding of neural pathways and his diagnostic innovations including deep tissue biopsy, nerve conduction tests (NCS), and clinical photography.

[1][2][3][4] The American neurologist Joseph Collins (1866–1950) wrote that Duchenne found neurology "a sprawling infant of unknown parentage which he succored to a lusty youth.

In opposition to his father's wishes that he become a sailor, and driven by a fascination with science, Duchenne enrolled at the University of Douai where he received his Baccalauréat at the age of 19.

[8] He then trained under a number of distinguished Paris physicians including René-Théophile-Hyacinthe Laënnec (1781–1826) and Baron Guillaume Dupuytren (1777–1835) before returning to Boulogne and setting up in practice there.

In 1835, Duchenne began experimenting with therapeutic "électropuncture" (a technique recently invented by François Magendie and Jean-Baptiste Sarlandière by which electric shock was administered beneath the skin with sharp electrodes to stimulate the muscles).

Were it not for this small, but remarkable, work, his next publication, the result of nearly 20 years of study, Duchenne's Physiology of Movements,[10] his most important contribution to medical science, might well have gone unnoticed.

Despite his unorthodox procedures, and his often uneasy relations with the senior medical staff with whom he worked, Duchenne's single-mindedness obtained him an international standing as a neurologist and researcher.

[11] Influenced by the fashionable beliefs of physiognomy of the 19th century, Duchenne wanted to determine how the muscles in the human face produce facial expressions which he believed to be directly linked to the soul of man.

It is these notions that he sought conclusively and scientifically to chart by his experiments and photography and it led to the publishing of The Mechanism of Human Physiognomy in 1862[13] (also entitled, The Electro-Physiological Analysis of the Expression of the Passions, Applicable to the Practice of the Plastic Arts.

He believed that only by electroshock and in the setting of elaborately constructed theatre pieces featuring gestures and accessory symbols could he faithfully depict the complex combinatory expressions resulting from conflicting emotions and ambivalent sentiments.

These melodramatic tableaux include a nun in "extremely sorrowful prayer" experiencing "saintly transports of virginal purity"; a mother feeling both pain and joy while leaning over a child's crib; a bare-shouldered coquette looking at once offended, haughty and mocking; and three scenes from Lady Macbeth expressing the "aggressive and wicked passions of hatred, of jealousy, of cruel instincts," modulated to varying degrees of contrary feelings of filial piety.

To help him locate and identify the facial muscles, Duchenne drew heavily upon the work of Charles Bell, who had included psychiatric patients in his studies.

The exact imitation of nature was for Duchenne the sine qua non of the finest art of whatever age, and although he praised the ancient Greek sculptors for unquestionably attaining an ideal of beauty, he nevertheless criticized them for their anatomical errors and failure to attend to the emotions.

[23] Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals written, in part, as a refutation of Sir Charles Bell's theologically doctrinaire physiognomy, was published in 1872.

In 1981, a modern audience was exposed to Duchenne's The Mechanism of Human Physiognomy when the book and its photographs were revealed - alongside illustrations of phrenology and evolutionary theory - on screen in the film version of John Fowles's novel, The French Lieutenant's Woman.

There, the protagonist, Charles Smithson, a young scientist, who "like most men of his time, was still faintly under the influence of the Lavater's Physiognomy,"[25] is intent on interpreting an alienated woman's true character from her expressions.

… In the end, Duchenne's Mecanisme de la Physionomie Humaine and the photographic stills from its experimental theater of electroshock excitations established the modern field on which the struggle to depict and thus discern the ever-elusive meanings of our coded faces continues even now to be waged.