Duino Elegies

He was then "widely recognized as one of the most lyrically intense German-language poets",[1] and began the elegies in 1912 while a guest of Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis at Duino Castle on the Adriatic Sea.

During this ten-year period, the elegies languished incomplete for long stretches of time as Rilke had frequent bouts with severe depression—some of which were related to the events of World War I and being conscripted into military service.

With a sudden, renewed burst of frantic writing which he described as a "boundless storm, a hurricane of the spirit"[2]—he completed the collection in February 1922 while staying at Château de Muzot in Veyras, Switzerland.

[10] While writing Das Marien-Leben (The Life of Mary) in January 1912, Rilke claimed that he heard a voice calling in the roar of the wind while walking along the cliffs near the castle, speaking the words that would become the first lines of the Duino Elegies: "Wer, wenn ich schriee, hörte mich denn aus der Engel Ordnungen?"

[20] Rilke and Klossowska wanted to move into the Château de Muzot, a 13th-century manor house that lacked gas and electricity, near Veyras in the Rhone Valley, but they had trouble negotiating the lease.

"[28] Immediately after completing the Elegies, he wrote Lou Andreas-Salomé that he had finished "all in a few days; it was a hurricane, as at Duino that time: all that was fiber, fabric in me, framework, cracked and bent.

The poet Albrecht Schaeffer [de], who is associated with the literary circle of Stefan George, dismissed the poems as "mystical blather" and described their "secular theology" as "impotent gossip".

[30] Novelist Hermann Hesse describes Rilke as evolving into his best poetry with the Duino Elegies, that "at each stage now and again the miracle occurs, his delicate, hesitant, anxiety-prone person withdraws, and through him resounds the music of the universe; like the basin of a fountain he becomes at once instrument and ear".

[32] Theodor W. Adorno wrote "But the fact that the neoromantic lyric sometimes behaves like the jargon, or at least timidly readies the way for it, should not lead us to look for the evil of the poetry simply in its form.

The evil, in the neoromantic lyric, consists in the fitting out of the words with a theological overtone, which is belied by the condition of the lonely and secular subject who is speaking there: religion as ornament.

At the onset of the First Elegy, Rilke describes this frightened experience, defining beauty as ... nothing but beginning of Terror we're still just able to bear, and why we adore it so is because it serenely disdains to destroy us.

[38] As mankind came in contact with the terrifying beauty represented by these angels, Rilke was concerned with the experience of existential angst in trying to come to terms with the coexistence of the spiritual and earthly.

He portrayed human beings as alone in a universe where God is abstract and possibly non-existent, "where memory and patterns of intuition raise the sensitive consciousness to a realization of solitude".

[49] In a 1923 letter to Nanny von Escher, Rilke confided: Two inmost experiences were decisive for their [i.e., The Sonnets to Orpheus and The Duino Elegies] production: The resolve that grew up more and more in my spirit to hold life open toward death, and on the other side, the spiritual need to situate the transformation of love in this wider whole differently than was possible in the narrower orbit of life (which simply shut out death as the other).

[51] Rilke depicted the six artists about to begin their performance, and that they were used as a symbol of "human activity ... always travelling and with no fixed abode, they are even a shade more fleeting than the rest of us, whose fleetingness was lamented".

Further, Rilke in the poem described these figures as standing on a "threadbare carpet" to suggest "the ultimate loneliness and isolation of Man in this incomprehensible world, practicing their profession from childhood to death as playthings of an unknown will ... before their 'pure too-little' had passed into 'empty too-much'".

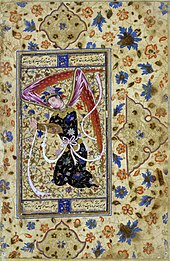

[56] In the United States, his poetry has been read as wisdom literature, and has been compared to the thirteenth-century Sufi (Muslim) mystic Rumi (1207–1273), and 20th century Lebanese-American poet Kahlil Gibran (1883–1931).

[62] The novelist Thomas Pynchon novel Gravity's Rainbow shows echoes of Rilke;[63] its first lines mirror the first lines of the first elegy, with a "sound [that] is [the] scream of a V-2 rocket hitting London in 1944"; and The New York Times reviewer of Gravity's Rainbow wrote that, "the book could be read as a serio-comic variation on Rilke's Duino Elegies and their German Romantic echoes in Nazi culture".

[64] Rilke's Duino Elegies influenced Hans-Georg Gadamer's theories of hermeneutics—understanding how an observer (i.e. reader, listener, or viewer) interprets cultural artifacts (i.e. works of literature, music, or art) as a series of distinct encounters.

[66] According to Gadamer, Rilke's point toward how to approach those limits, by making these part of ourselves interpretation and reinterpretation can we address the existential problems of humanity's significance and impermanence.