History of the Jews in the Netherlands

Since Portuguese Jews had not lived under rabbinic authority for decades, the first generation of those embracing their ancestral religion had to be formally instructed in Jewish belief and practice.

Both groups migrated for reasons of religious liberty, to escape persecution, now able to live openly as Jews in separate organized, autonomous Jewish communities under rabbinic authority.

Various medieval chronicles mention this, e.g., those of Radalphus de Rivo (c. 1403) of Tongeren, who wrote that Jews were murdered in the Brabant region and in the city of Zwolle because they were accused of spreading the Black Death.

In 1349, the Duke of Guelders was authorized by the Emperor Louis IV of the Holy Roman Empire to receive Jews in his duchy, where they provided services, paid a tax, and were protected by the law.

In 1477, by the marriage of Mary of Burgundy to the Archduke Maximilian, son of Emperor Frederick III, the Netherlands were united to Austria and its possessions passed to the crown of Spain.

In the sixteenth century, owing to the persecutions of Charles V and Philip II of Spain, the Netherlands became involved in a series of desperate and heroic struggles against this growing political and Catholic religious hegemony.

In Spain, converted Jews called conversos or New Christians came under the jurisdiction of the Inquisition, which was vigilant against their continuing to practice Judaism in secret, as crypto-Jews, or the pejorative term Marrano (see also anusim).

Jews forced to convert did not immediately face penalties for privately practicing Judaism while publicly being Catholics, so that there continued to be a strong Jewish presence there.

[10] Portuguese Jewish merchants had already settled in Antwerp in the southern Netherlands, an entrepôt for trade in Iberian commodities, such as sugar, silver bullion, spices, and tobacco.

In the late 16th century, some Sephardic Jews from the Iberian peninsula (Sepharad is the Hebrew name for Iberia) started to settle in the Netherlands, especially Amsterdam, gaining a foothold, but with an unclear status.

[14] Creating a sacred space for Jewish worship was initially a problem, since Amsterdam authorities did not envision Jews to be included in the notion of religious toleration.

Garces was burial place was located outside of the formal boundaries of the cemetery, in "a fringe reserved for uncircumcised marginal types not fully belonging to the community.

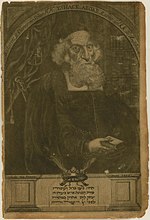

[citation needed] There are a number of notable Sephardic Jews in Amsterdam in the 17th century, including Saul Levi Morteira, a rabbi and anti-Christian polemicist.

"Jews of the Portuguese Nation" worked in common cause with the people of Amsterdam and contributed materially to the prosperity of the country; they were strong supporters of the House of Orange and were protected by the Stadholder.

[35] In a letter dated 25 November 1622, King Christian IV of Denmark invited Jews of Amsterdam to settle in Glückstadt, where, among other privileges, they were assured the free exercise of their religion.

The ambitious schemes of the Dutch for the conquest of Brazil were carried into effect by Francisco Ribeiro, a Portuguese captain, who is said to have had Jewish relations in Holland.

The Sephardic Jews of Amsterdam strongly supported the Dutch Republic in its struggle with Portugal for the possession of Brazil, which started in Recife with the arrival of Count Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen in 1637.

In 1642 about 600 Jews left Amsterdam for Brazil, accompanied by two distinguished scholars, Isaac Aboab da Fonseca and Moses Raphael de Aguilar.

After the Portuguese regained the territory that Netherlands had taken in the sugar growing region around Recife in 1654, they sought refuge in other Dutch colonies, including the island of Curaçao in the Caribbean and New Amsterdam (Manhattan) in North America.

In addition, they were displaced by the violence of the Thirty Year War (1618–1648) in other parts of northern Europe, and local expulsions, as well as the 1648 Khmelnytsky uprising in what was then eastern Poland.

[37][38] The National Convention, on 2 September 1796, proclaimed this resolution: "No Jew shall be excluded from rights or advantages which are associated with citizenship in the Batavian Republic, and which he may desire to enjoy."

From 1806 to 1810 the Kingdom of Holland was ruled by the brother of Napoleon, Louis Bonaparte, whose intention it was to so amend the condition of the Jews that their newly acquired rights would become of real value to them; the shortness of his reign, however, prevented him from carrying out his plans.

For example, after having changed the market-day in some cities (Utrecht and Rotterdam) from Saturday to Monday, he abolished the use of the "Oath More Judaico" in the courts of justice, and administered the same formula to both Christians and Jews.

[42] Shortly after William VI arrived at Scheveningen, and was crowned king on 11 December, Chief Rabbi Lehmans of The Hague organized a special thanksgiving service, asking for protection for the allied armies on 5 January 1814.

[73] Esther Voet, director of the Centrum Informatie en Documentatie Israël [nl], advised the Knesset in 2014 that Dutch Jews were concerned about what they perceived as increasing antisemitism in the Netherlands.

Part of NIKMedia is the Joodse Omroep,[100] which broadcasts documentaries, stories and interviews on a variety of Jewish topics every Sunday and Monday on the Nederland 2 television channel (except from the end of May until the beginning of September).

The close proximity of the two cultures also led to intermarriage at a higher rate than was known elsewhere, and in consequence many Jews of Dutch descent have family names that seem to belie their religious affiliation.

In 1812, while the Netherlands was under Napoleonic rule, all Dutch residents (including Jews) were obliged to register surnames with the civic authorities; previously only Sephardim had complied with this.

However, all the major colonial powers were competing fiercely for control of trade routes; the Dutch were relatively unsuccessful and during the 18th century, their economy went into decline.

This caused a large number of small Jewish communities to collapse completely (ten adult males were required to conduct major religious ceremonies).