Dutch people

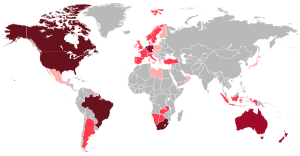

Dutch people and their descendants are found in migrant communities worldwide, notably in Argentina, Aruba, Australia,[29] Brazil, Canada,[30] Caribbean Netherlands, Curaçao, Germany, Guyana, Indonesia, New Zealand, Sint Maarten, South Africa,[31] Suriname, and the United States.

[32] The Low Countries were situated around the border of France and the Holy Roman Empire, forming a part of their respective peripheries and the various territories of which they consisted had become virtually autonomous by the 13th century.

Following the end of the migration period in the West around 500, with large federations (such as the Franks, Vandals, Alamanni and Saxons) settling the decaying Roman Empire, a series of monumental changes took place within these Germanic societies.

Eventually, in 358, the Salian Franks, one of the three main subdivisions among the Frankish alliance,[40] settled the area's Southern lands as foederati; Roman allies in charge of border defense.

The current Dutch-French language border has (with the exception of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais in France and Brussels and the surrounding municipalities in Belgium) remained virtually identical ever since, and could be seen as marking the furthest pale of gallicisation among the Franks.

The medieval cities of the Low Countries, especially those of Flanders, Brabant and Holland, which experienced major growth during the 11th and 12th centuries, were instrumental in breaking down the already relatively loose local form of feudalism.

[49][50][51] During the early 14th century, beginning in and inspired by the County of Flanders,[52] the cities in the Low Countries gained huge autonomy and generally dominated or greatly influenced the various political affairs of the fief, including marriage succession.

[citation needed] The subsequently issued Great Privilege met many of these demands, which included that Dutch, not French, should be the administrative language in the Dutch-speaking provinces under Burgundian rule (i.e. Flanders, Brabant and Holland) and that the States-General had the right to hold meetings without the monarch's permission or presence.

The overall tenor of the document (which was declared void by Mary's son and successor, Philip IV) aimed for more autonomy for the counties and duchies, but nevertheless all the fiefs presented their demands together, rather than separately.

Further centralised policies of the Habsburgs (like their Burgundian predecessors) again met with resistance, but, peaking with the formation of the collateral councils of 1531 and the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549 creating the Seventeen Provinces, were still implemented.

[citation needed] By the middle of the 16th century an overarching, 'national' (rather than 'ethnic') identity seemed in development in the Habsburg Netherlands, when inhabitants began to refer to it as their 'fatherland' and were beginning to be seen as a collective entity abroad; however, the persistence of language barriers, traditional strife between towns, and provincial particularism continued to form an impediment to more thorough unification.

[55] Following excessive taxation together with attempts at diminishing the traditional autonomy of the cities and estates in the Low Countries, followed by the religious oppression after being transferred to Habsburg Spain, the Dutch revolted, in what would become the Eighty Years' War.

[56] However, during the war it became apparent that the goal of liberating all the provinces and cities that had signed the Union of Utrecht, which roughly corresponded to the Dutch-speaking part of the Spanish Netherlands, was unreachable.

[citation needed] The (re)definition of Dutch cultural identity has become a subject of public debate following the increasing influence of the European Union and the influx of non-Western immigrants in the post-World War II period.

As did many European ethnicities during the 19th century,[62] the Dutch also saw the emerging of various Greater Netherlands- and pan-movements seeking to unite the Dutch-speaking peoples across the continent, while trying to counteract Pan-Germanic tendencies.

Other relatively well known features of the Dutch language and usage are the frequent use of digraphs like Oo, Ee, Uu and Aa, the ability to form long compounds and the use of slang, including profanity.

In the early 16th century, the Protestant Reformation began to form and soon spread in the Westhoek and the County of Flanders, where secret open-air sermons were held, called hagenpreken ('hedgerow orations') in Dutch.

Economically and culturally, the traditional centre of the region have been the provinces of North and South Holland, or today; the Randstad, although for a brief period during the 13th or 14th century it lay more towards the east, when various eastern towns and cities aligned themselves with the emerging Hanseatic League.

This was followed by a nationalist backlash during the late 19th and early 20th centuries that saw little help from the Dutch government (which for a long time following the Belgian Revolution had a reticent and contentious relationship with the newly formed Belgium and a largely indifferent attitude towards its Dutch-speaking inhabitants)[100] and, hence, focused on pitting "Flemish" culture against French culture, resulting in the forming of the Flemish nation within Belgium, a consciousness of which can be very marked among some Dutch-speaking Belgians.

[101][page needed] The largest patterns of human genetic variation within the Netherlands show strong correlations with geography and distinguish between: (1) North and South; (2) East and West; and (3) the middle-band and the rest of the country.

The distribution of gene variants for eye colour, metabolism, brain processes, body height and immune system show differences between these regions that reflect evolutionary selection pressures.

[102] The largest genetic differences within the Netherlands are observed between the North and the South (with the three major rivers – Rijn, Waal, Maas – as a border), with the Randstad showing a mixture of these two ancestral backgrounds.

[110] Since World War II, Dutch emigrants have mainly departed the Netherlands for Canada, the Federal Republic of Germany, the United States, Belgium, Australia, and South Africa, in that order.

[115] In the early-to-mid-16th century, Dutch Mennonites began to move from the Low Countries (especially Friesland and Flanders) to the Vistula delta region, seeking religious freedom and exemption from military service.

[121] As the number of Europeans—particularly women—in the Cape swelled, South African whites closed ranks as a community to protect their privileged status, eventually marginalising Coloureds as a separate and inferior racial group.

[124] Since VOC employees proved inept farmers, tracts of land were granted to married Dutch citizens who undertook to spend at least twenty years in South Africa.

[127] Some vrijburgers eventually turned to cattle ranching as trekboers, creating their own distinct sub-culture centered around a semi-nomadic lifestyle and isolated patriarchal communities.

[128] Afrikaners are dominated by two main groups, the Cape Dutch and Boers, which are partly defined by different traditions of society, law, and historical economic bases.

Due to Australia experiencing a shortage of agricultural and metal industry workers it, and to a lesser extent New Zealand, seemed an attractive possibility, with the Dutch government actively promoting emigration.

There are a considerable number of people who are descendants of the Dutch colonists in Paraíba (for example in Frederikstad, today João Pessoa), Pernambuco, Alagoas and Rio Grande do Norte.