French war planning 1920–1940

The Mechelen Incident was a catalyst for the doubts about Fall Gelb and led to the Manstein plan, a bold, almost reckless, gamble for an attack further south through the Ardennes.

After the territorial changes in the Treaty of Versailles (28 June 1919) transferred the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine to France, natural resources, industry and population close to the frontier, vital for the prosecution of another war of exhaustion, meant that the French army would not be able to gain time by retreating into the interior as it had in 1914.

The French Army was responsible for frontier protection under the Conseil supérieur de la guerre (CSG, Supreme War Council), which was revived on 23 January 1920.

[1] By 1918, French conscripts were receiving no more than three months' training and after the war, it was considered that the size of the army should be determined by the number of divisions needed for security.

From 17 December 1926 to 12 October 1927, the Frontier Defence Commission reported to the CSG that fortifications should be built from Metz to Thionville and Longwy, to protect the Moselle Valley and the mineral resources and industry of Lorraine.

On 12 October 1927, the CSG adopted the system recommended by Pétain, of large and elaborately fortified defences from Metz to Thionville and Longwy, at Lauter and Belfort, on the north-east frontier, with covered infantry positions between the main fortifications.

André Maginot, the Minister of War (1922–1924, 1929–1930 and 1931–1932) became the driving force for obtaining the money to fortify the north-eastern frontier, sufficient to resist a German invasion for three weeks, to give time for the French army to mobilise.

Maisons Fortes were to be built near the frontier as permanently garrisoned works, whose men would alert the army, blow bridges and erect roadblocks, for which materials were dumped.

Artificial obstacles of 4 to 6 rows of upright railway line, 10 ft (3.0 m)-long set in concrete and of random depth and covered by barbed wire.

The resources and equipment needed to use the Ardennes route would take so long that the French army expected to have ample time to reinforce the area.

A fortified defence in depth would be impractical because the industrial conurbation of Lille, Tourcoing, Roubaix and Valenciennes and its railway communications, obstructed the construction of a prepared battlefield with barbed wire, trenches and tank traps.

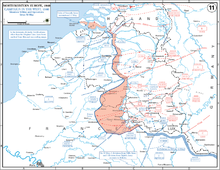

By May 1940, there had been an exchange of the general nature of French and Belgian defence plans but little co-ordination, especially against a German offensive, westwards through Luxembourg and the east of Belgium.

Most of the French mobile forces were assembled along the Belgian border, ready to make a quick move forward and take up defensive positions before the Germans arrived.

For the first fortnight of the war, Maurice Gamelin, General of the army and Commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces, favoured Plan E because of the example of the fast German advances in Poland after the invasion of 1 September 1939.

A warning that the German offensive would begin on 12 November was received from various sources, with the main panzer effort to be made against the Low Countries (Belgium and the Netherlands) and the Allied forces were alerted.

The Germans assumed that the captured documents had reinforced the Allied appreciation of their intentions, and on 30 January, some details of Aufmarschanweisung N°3, Fall Gelb were amended.

French intelligence uncovered a transfer of German divisions from the Saar to the north of the Moselle but failed to detect the redeployment from the Dutch border to the Eiffel–Moselle area.

[18] By late 1939, the Belgians had improved the defences along the Albert Canal and increased the readiness of the army; Gamelin and GQG began to consider the possibility of advancing further than the Escaut.

The gap from the Dyle to Namur north of the Sambre, with Maastricht and Mons on either side, had few natural obstacles and was a traditional route of invasion, leading straight to Paris.

On 8 November, Gamelin directed that a German invasion of the Netherlands must not be allowed to pass round the west of Antwerp by gaining the south bank of the Scheldt.

[26] The French found that the Moerdijk causeway had been captured by German paratroops, cutting the link between southern and northern Holland, forcing the Dutch Army to retire north towards Amsterdam and Rotterdam.

[27] By 14 May, much of the Netherlands had been overrun and the Seventh Army found that fighting in the close country among the canals of southern Holland and north-western Belgium proved costly against the German combination of ground and air attack.

[31] By noon on 11 May, the German glider troops on the roof of Eben-Emael, had forced the garrison to surrender and two bridges over the Maas (Meuse) at Vroenhoven and Veldwezelt near Maastricht were captured.

[38] Next day, parts of the BEF began to retreat towards the Dender river as the British reorganised to face the threat on their right flank against the Germans who had broken through south of the First Army.

Billotte was still unsure of the main German effort and hesitated to direct it to the Ninth Army until 14 May; the order took until the afternoon to arrive and the march was obstructed by refugees on the roads.

Doughty wrote that Gamelin gained confidence in the capacity of the Allied armies, adopting a grand strategy of dubious value over the objections of some of the most senior French generals.

Gamelin imposed the Breda variant unilaterally, without consultation with the governments of Belgium and the Netherlands, which refused to make detailed arrangements for joint military action, unless invaded.

[45] Gamelin was an officer who had risen through the French military hierarchy with a reputation for caution, yet he took a great gamble with the Dyle plan, which was not inherently reckless until the Breda variant.

[46] The Dyle plan was laid down in thick document volumes for each headquarters, Prioux complaining of "enormous dossiers...full of corrections, additions, annexes, appendices, etc".

With no forces available against the penetration at Sedan, the XVI Panzer Corps was no longer needed for the feint in Belgium and was transferred to Heeresgruppe A (Army Group A) on 18 May.