Eric Burhop

A graduate of the University of Melbourne, Burhop was awarded an 1851 Exhibition Scholarship to study at the Cavendish Laboratory under Lord Rutherford.

In early 1945, Harrie Massey offered Burhop a position as a lecturer in the Mathematics Department at University College, London.

While never formally charged with atomic espionage or so much as directly questioned by investigators, due to his leftist political views, anti-nuclear activism as well as his personal links to exposed Soviet spies, Burhop was the subject of comprehensive surveillance on the part of the UK, US and Australia's counterespionage agencies in the 1940s–1950s, a fact that was publicised in 2019.

[2] For a master's research problem, Professor Thomas Laby had Burhop investigate the probability K shell ionisation by electron impact by measuring the intensity of the resultant X-ray emissions.

[5][6] The thesis was good enough, though, for Burhop to be awarded an 1851 Exhibition Scholarship to study at Cambridge University's Cavendish Laboratory under Lord Rutherford in 1933.

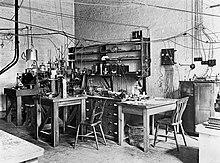

In 1932, Cavendish laboratory scientists John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton split the atomic nucleus, James Chadwick discovered the neutron, and Patrick Blackett and Giuseppe Occhialini confirmed the existence of the positron.

At Cambridge he encountered political debate generated by the suffering caused by the Great Depression and the rise of fascism in Europe.

[11] Burhop established the first research program in the field in an Australian university, employing scientific equipment that he brought back from Britain.

[2][4] After the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, the Physics Department worked on the development of optical munitions, particularly aluminised mirrors for aerial photography.

In February 1942, Oliphant persuaded Laby to release Burhop and Leslie Martin to work on microwave radar at the Radiophysics Laboratory in Sydney.

[12] In January 1944, Oliphant had Sir David Rivett, the head of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, release Burhop to work on the Manhattan Project,[13][14] the Allied effort to create atomic bombs.

In May 1944, Burhop joined Oliphant's British Mission at the Ernest Lawrence's Radiation Laboratory at the University of California in Berkeley.

[5][17] Burhop's work involved the occasional visit to the Manhattan Project's Y-12 electromagnetic faculty at Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Wartime shortages persisted, and the college had suffered bombing damage, so the Mathematics Department were located in temporary quarters.

In 1957, he collaborated with Occhialini and C. F. Powell on a five-nation study of K mesons and their interaction with atomic nuclei that went on for several years, and produced a wealth of new results, including the first observation of a double lambda hypernucleus.

He spent the 1962–63 academic year on secondment to CERN, and was secretary of a committee chaired by Edoardo Amaldi that drew up its policy for accelerator development.

The machines the committee recommended, the Intersecting Storage Rings and the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) were built, and became an important part of physics research in Europe for decades to come.

[18][1] Following Klaus Fuchs voluntarily confessing in January 1950 he had been spying for the Soviets, the UK government received a report from the FBI that said that "as late as 1945 an Australian atomic scientist who [had] worked on an Atomic Energy project was in close touch with Communist Party members in Brooklyn, New York, and through them with the highest Communist officials in the United States.

[20] A new passport was issued after he gave the Foreign Secretary a written assurance that he would not seek to travel to the Soviet Union or other Iron Curtain countries.

[1] Like many scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project, Burhop was concerned about the dangers of nuclear weapons, and addressed over 500 public meetings to raise awareness of the subject.