E. T. A. Hoffmann

[5] His father, Christoph Ludwig Hoffmann (1736–97), was a barrister in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia), as well as a poet and amateur musician who played the viola da gamba.

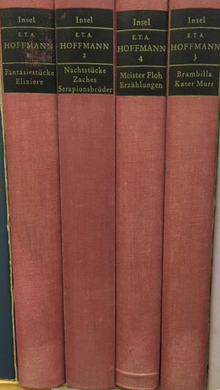

Although she died when he was only three years old, he treasured her memory (a character in Hoffmann's Lebensansichten des Katers Murr is named after her) and embroidered stories about her to such an extent that later biographers sometimes assumed her to be imaginary, until proof of her existence was found after World War II.

The provincial setting was not, however, conducive to technical progress, and despite his many-sided talents he remained rather ignorant of both classical forms and of the new artistic ideas that were developing in Germany.

[7] In February 1796, her family protested against his attentions and, with his hesitant consent, asked another of his uncles to arrange employment for him in Glogau (Głogów), Prussian Silesia.

It was there that Hoffmann first attempted to promote himself as a composer, writing an operetta called Die Maske and sending a copy to Queen Luise of Prussia.

By the time the latter responded, Hoffmann had passed his third round of examinations and had already left for Posen (Poznań) in South Prussia in the company of his old friend Hippel, with a brief stop in Dresden to show him the gallery.

This was the first time he had lived without supervision by members of his family, and he started to become "what school principals, parsons, uncles, and aunts call dissolute.

The problem was solved by "promoting" Hoffmann to Płock in New East Prussia, the former capital of Poland (1079–1138), where administrative offices were relocated from Thorn (Toruń).

He visited the place to arrange lodging, before returning to Posen where he married Mischa (Maria or Marianna Thekla Michalina Rorer, whose Polish surname was Trzcińska).

[10] This was one of the few good times of a sad period of his life, which saw the deaths of his uncle J. L. Hoffmann in Berlin, his Aunt Sophie, and Dora Hatt in Königsberg.

In Warsaw he found the same atmosphere he had enjoyed in Berlin, renewing his friendship with Zacharias Werner, and meeting his future biographer, a neighbour and fellow jurist called Julius Eduard Itzig (who changed his name to Hitzig after his baptism).

He moved in the circles of August Wilhelm Schlegel, Adelbert von Chamisso, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Rahel Levin and David Ferdinand Koreff.

But Hoffmann's fortunate position was not to last: on 28 November 1806, during the War of the Fourth Coalition, Napoleon Bonaparte's troops captured Warsaw, and the Prussian bureaucrats lost their jobs.

In January 1807, Hoffmann's wife and two-year-old daughter Cäcilia returned to Posen, while he pondered whether to move to Vienna or go back to Berlin.

Obtaining only meagre allowances, he had frequent recourse to his friends, constantly borrowing money and still going hungry for days at a time; he learned that his daughter had died.

He began work as music critic for the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, a newspaper in Leipzig, and his articles on Beethoven were especially well received, and highly regarded by the composer himself.

The theme alludes to the work of Jean Paul, who invented the term Doppelgänger the previous decade, and continued to exact a powerful influence over Hoffmann, becoming one of his earliest admirers.

When Joseph Seconda offered Hoffmann a position as musical director for his opera company (then performing in Dresden), he accepted, leaving on 21 April 1813.

But on 22 August, after the end of the armistice, the family was forced to relocate from their pleasant house in the suburbs into the town, and during the next few days the Battle of Dresden raged.

At the end of September 1814, in the wake of Napoleon's defeat, Hoffmann returned to Berlin and succeeded in regaining a job at the Kammergericht, the chamber court.

During the trial of "Turnvater" Jahn, the founder of the gymnastics association movement, Hoffmann found himself annoying Kamptz, and became a political target.

Hoffmann is one of the best-known representatives of German Romanticism, and a pioneer of the fantasy genre, with a taste for the macabre combined with realism that influenced such authors as Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849), Nikolai Gogol[13][14] (1809–1852), Charles Dickens (1812–1870), Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), George MacDonald (1824–1905),[15] Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881), Vernon Lee (1856–1935),[16] Franz Kafka (1883–1924) and Alfred Hitchcock (1899–1980).

Robert Schumann's piano suite Kreisleriana (1838) takes its title from one of Hoffmann's books (and according to Charles Rosen's The Romantic Generation, is possibly rather inspired by "The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr", in which Kreisler appears).

While disagreeing with E. F. Bleiler's claim that Hoffmann was "one of the two or three greatest writers of fantasy", Algis Budrys of Galaxy Science Fiction said that he "did lay down the groundwork for some of our most enduring themes".

[19] Historian Martin Willis argues that Hoffmann's impact on science fiction has been overlooked, saying "his work reveals a writer dynamically involved in the important scientific debates of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries."

Willis points out that Hoffmann's work is contemporary with Frankenstein (1818) and with "the heated debates and the relationship between the new empirical science and the older forms of natural philosophy that held sway throughout the eighteenth century."

...Hoffmann's work makes a considerable contribution to our understanding of the emergence of scientific knowledge in the early years of the nineteenth century and to the conflict between science and magic, centred mainly on the 'truths' available to the advocates of either practice.

...Hoffmann's balancing of mesmerism, mechanics, and magic reflects the difficulty in categorizing scientific knowledge in the early nineteenth century.