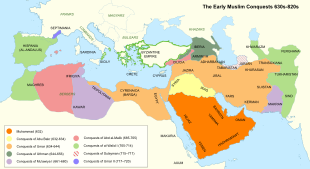

Early Muslim conquests

[38] In response to the loss of Syria, the Byzantines developed the phylarch system of using Armenian and Arab Christian auxiliaries living on the frontier to provide a "shield" to counter raiding by the Muslims into the empire.

Arab-Muslim raids that followed the Ridda Wars prompted the Byzantines to send a major expedition into southern Palestine, which was defeated by the Arab forces under command of Khalid ibn al-Walid at the Battle of Ajnadayn in 634.

[57] In the frontier area where Anatolia met Syria, the Byzantine state evacuated the entire population and laid waste to the countryside, creating a no man's land where any invading army would find no food.

[67] After an Arab incursion into Sasanian territories, the shah Yazdgerd III, who had just ascended the Persian throne, raised an army to resist the conquerors,[68] although many marzbans refused to help.

[70] As the conquerors slowly covered the vast distances of Iran punctuated by hostile towns and fortresses, Yazdgerd III retreated, finally taking refuge in Khorasan, where he was assassinated by a local satrap in 651.

[79] The Umayyad caliphs are well-remembered for sponsoring a cultural "golden age" in Islamic history—for example, by building the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and for making Damascus into the capital of a "superpower" that stretched from Portugal to Central Asia, covering the vast territory from the Atlantic Ocean to the borders of China.

[85] Fred Donner writes that the advent of Islam "revolutionized both the ideological bases and the political structures of the Arabian society, giving rise for the first time to a state capable of an expansionist movement.

[81] The Sasanian Empire, which had lost the latest round of hostilities with the Byzantines, was also affected by a crisis of confidence, and its elites suspected that the ruling dynasty had forfeited the favor of the gods.

[81] Arab commanders also made liberal use of agreements to spare lives and property of inhabitants in case of surrender and extended exemptions from paying tribute to groups who provided military services to the conquerors.

[89] Additionally, the Byzantine persecution of Christians opposed to the Chalcedonian creed in Syria and Egypt alienated elements of those communities and made them more open to accommodation with the Arabs once it became clear that the latter would let them practice their faith undisturbed as long as they paid tribute.

[94][95] Arab incursions southward from Sindh were repulsed by the armies of Gurjara and Chalukya kingdoms, and further Islamic expansion was checked by the Rashtrakuta dynasty, which gained control of the region shortly after.

[97][98] The Berber chief Kusayla and an enigmatic leader referred to as Kahina (prophetess or priestess) seem to have mounted effective, if short-lived resistance to Muslim rule at the end of the 7th century, but the sources do not give a clear picture of these events.

[109] In 674, a Muslim force led by Ubaidullah Ibn Zayyad attacked Bukhara, the capital of Sogdia, which ended with the Sogdians agreeing to recognize the Umayadd caliph Mu'awiaya as their overlord and to pay tribute.

[110] The expansion lost its momentum when Qutayba was killed during an army mutiny and the Arabs were placed on the defensive by an alliance of Sogdian and Türgesh forces with support from Tang China.

Further south in the Balkh region, in Bamiyan, indication of Sasanian authority diminishes, with a local dynasty apparently ruling from late antiquity, probably Hephthalites subject to the Yabghu of the Western Turkic Khaganate.

[117] Although Muslim dominion was finally established by the time the Umayyads acceded to power in 661, it was not able to implant itself solidly in the country, and Armenia experienced a national and literary efflorescence over the next century.

[117] As with Armenia, Arab advances into other lands of the Caucasus region, including Georgia, had as their end assurances of tribute payment and these principalities retained a large degree of autonomy.

[120] In the east, although Arabs were able to establish control over most Sasanian-controlled areas of modern Afghanistan after the fall of Persia, the Kabul region resisted repeated attempts at invasion and would continue to do so until it was conquered by the Saffarids three centuries later.

[122] Nicolle writes that the series of Islamic conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries was "one of the most significant events in world history", leading to the creation of "a new civilisation", the Islamicised and Arabised Middle East.

[123] Islam, which had previously been confined to Arabia, became a major world religion, while the synthesis of Arab, Byzantine, and Sasanian elements led to distinctive new styles of art and architecture emerging in the Middle East.

[124] English historian Edward Gibbon writes in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: Under the last of the Umayyads, the Arabian empire extended two hundred days journey from east to west, from the confines of Tartary and India to the shores of the Atlantic Ocean ... We should vainly seek the indissoluble union and easy obedience that pervaded the government of Augustus and the Antonines; but the progress of Islam diffused over this ample space a general resemblance of manners and opinions.

[91] Two fundamental policies were implemented during the reign of the second caliph Umar (r. 634–644): the Bedouins would not be allowed to damage agricultural production of the conquered lands, and the leadership would cooperate with the local elites.

[133] These circumstances provoked opposition from non-Arab converts, whose ranks included many active soldiers, and helped set the stage for the civil war which ended with the fall of the Umayyad dynasty.

[135] According to Bernard Lewis, available evidence suggests that the change from Byzantine to Arab rule was "welcomed by many among the subject peoples, who found the new yoke far lighter than the old, both in taxation and in other matters".

[149] Other early 20th century scholars suggest that non-Muslims converted to Islam en masse in order to escape the poll tax, but this theory has been challenged by more recent research.

[150] After the end of military operations, which involved sacking of some monasteries and confiscation of Zoroastrian fire temples in Syria and Iraq, the early caliphate was characterized by religious tolerance and peoples of all ethnicities and religions blended in public life.

[153] There is no evidence for public display of Islam by the state before the reign of Abd al-Malik (685–705), when Quranic verses and references to Muhammad suddenly became prominent on coins and official documents.

[154] Islamic law followed the Byzantine precedent of classifying subjects of the state according to their religion, in contrast to the Sasanian model which put more weight on social than on religious distinctions.

[155] In theory, like the Byzantine empire, the caliphate placed severe restrictions on paganism, but in practice most non-Abrahamic communities of the former Sasanian territories were classified as possessors of a scripture (ahl al-kitab) and granted protected (dhimmi) status.

[159] The Pact of Umar, which stipulated that Muslims must "do battle to guard" the dhimmis and "put no burden on them greater than they can bear", was not always upheld, but it remained "a steadfast cornerstone of Islamic policy" into early modern times.