Early history of Pomerania

[1] A climate change in 8000 BC[2] allowed hunters and foragers of the Ertebølle-Ellerbek culture to continuously inhabit the area.

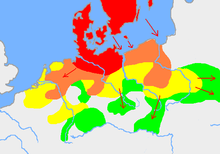

[12] Veneti, Germanic peoples like Goths, Rugians, and Gepids, and Slavs are assumed to have been the bearers of these cultures or parts thereof.

Hamburgian reindeer hunters were the first humans to occupy the plains freed from the retreating glaciers in north-central Europe.

[18] That may be due to Pomerania's location within the fall-out zone of the Laacher See eruption, which in 10970 BC covered the area with a tephra layer and is probably responsible for the emergence of the Bromme techno-complex from the Federmesser one by separating it from the southern groups.

[19] A worked giant deer antler and a sharpened horse rib from the Endingen IV Federmesser site were 14C-dated to 11555 ±100 BP and 11830 ±50 BP, respectively, and together with a giant deer skull from Mecklenburg represent the oldest absolutely dated human traces in northeastern Germany.

[25] While primarily hunters, it is assumed that the mesolithic people were also foraging, fishing, and even farming on a most primitive scale.

[34] The impact of the late neolithic Corded Ware culture on Western Pomerania was not as strong, but traceable.

For example, both Funnelbeaker and Corded Ware culture artefacts were found in a Megalith tomb near Groß Zastrow.

[25] During the mid-Neolithic Age, small populations belonging to the Comb Ceramic or Pit-comb ware culture were traced in Pomerania.

[38] Based on linguistic analyses of toponymes, Marija Gimbutas and others proposed a culture of Pomeranian Balts from the mouth of the Oder, and the whole Vistula basin to Silesia in the South-West.

[8][38] People of this culture burned their dead and buried the ashes in urns, which were typically placed in urnfields but also in tumuli.

[8] Numerous archeological findings of imported Scandinavian products prove contacts to Nordic Bronze Age peoples.

[8][38][40] These contacts and the Scandinavian influence on Pomerania was so considerable that this region is sometimes included in the Nordic Bronze Age culture.

[38] The eastern or Kashubian group of the Pomeranian Lusatian culture, characterized by burial rites were burned ashes were placed in burial mounds with stone constructions, imported their metalworks technologies from the South via the Vistula river as well as from the North via the Baltic Sea.

Settlements and urn grave fields with artefacts were found e.g. in the then densely settled Greifswald area.

[45] The Oder group, formerly thought to have emerged after an immigration from Bornholm, is now thought to have evolved from a local population formerly belonging to the Pomeranian culture and the Göritz group of the Lusatian culture, who first adapted to new habits and later mingled with a Germanic population from the West.

Artefacts, settlements and tombs from this period belong to the coastal group of the Roman Iron Age and are heavily influenced by the material culture of the Oder and Vistula area.

[49] Slag from the smelting of iron was found in many settlements, also imported goods, primarily from the Roman provinces, as well as silver and gold.

[54] Though rather scarce, Gustow group settlements were located on better soil due to the increasing importance of plant cultivation.

This culture dominated the area of Farther Pomerania northeast of the Ihna river, most of Pomerelia and northern Mazovia.

While in the past, German and Polish historians had associated them with the Goths or Slavs, respectively, recent hypotheses suggest they were a heterogeneous people, though scholarship is divided on whom to include therein; suggestions include the Veleti, Germanic peoples (Goths, Rugians, and Gepids) and possibly Slavs.

[13][59] The Dębczyn group might comprise the archaeological remnants of Tacitus' Lemovii, probably identical with Widsith's Glommas, who are believed to have been the neighbors of the Rugians, a tribe dwelling at the Pomeranian coast before the migration period.

[13] From the same period these treasures were hidden, both hoards of and single solidi have been found, coined by Valentinian III (425-455) and Anastasius I (491-518).

[14] In the late 5th and early 6th centuries, large grave fields were set up in the coastal areas, which differ from the Debzcyn group type and show Scandinavian analogies.

[14] It is assumed that Burgundians, Goths and Gepids with parts of the Rugians left Pomerania during the late Roman Age, and that during the migration period, remnants of Rugians, Vistula Veneti, Vidivarii and other, Germanic tribes remained and formed units that were later Slavicized.

[14] The Vidivarii themselves are described by Jordanes in his Getica as a melting pot of tribes who in the mid-6th century lived at the lower Vistula.

[62] One hypothesis, based on the sudden appearance of large amounts of Roman solidi and migrations of other groups after the breakdown of the Hun empire in 453, suggest a partial re-migration of earlier emigrants to their former northern homelands.