Earth radius

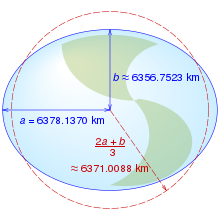

A globally-average value is usually considered to be 6,371 kilometres (3,959 mi) with a 0.3% variability (±10 km) for the following reasons.

) is sometimes used as a unit of measurement in astronomy and geophysics, a conversion factor used when expressing planetary properties as multiples or fractions of a constant terrestrial radius; if the choice between equatorial or polar radii is not explicit, the equatorial radius is to be assumed, as recommended by the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

[1] Earth's rotation, internal density variations, and external tidal forces cause its shape to deviate systematically from a perfect sphere.

[a] Local topography increases the variance, resulting in a surface of profound complexity.

Strictly speaking, spheres are the only solids to have radii, but broader uses of the term radius are common in many fields, including those dealing with models of Earth.

When considering the Earth's real surface, on the other hand, it is uncommon to refer to a "radius", since there is generally no practical need.

While specific values differ, the concepts in this article generalize to any major planet.

[4] The variation in density and crustal thickness causes gravity to vary across the surface and in time, so that the mean sea level differs from the ellipsoid.

Like a torus, the curvature at a point will be greatest (tightest) in one direction (north–south on Earth) and smallest (flattest) perpendicularly (east–west).

The corresponding radius of curvature depends on the location and direction of measurement from that point.

In summary, local variations in terrain prevent defining a single "precise" radius.

Historically, these models were based on regional topography, giving the best reference ellipsoid for the area under survey.

[6] It is an idealized surface, and the Earth measurements used to calculate it have an uncertainty of ±2 m in both the equatorial and polar dimensions.

When identifying the position of an observable location, the use of more precise values for WGS-84 radii may not yield a corresponding improvement in accuracy.

The value for the polar radius in this section has been rounded to the nearest 0.1 m, which is expected to be adequate for most uses.

If one point had appeared due east of the other, one finds the approximate curvature in the east–west direction.

[f] This Earth's prime-vertical radius of curvature, also called the Earth's transverse radius of curvature, is defined perpendicular (orthogonal) to M at geodetic latitude φ[g] and is[11] N can also be interpreted geometrically as the normal distance from the ellipsoid surface to the polar axis.

In geophysics, the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG) defines the Earth's arithmetic mean radius (denoted R1) to be[2] The factor of two accounts for the biaxial symmetry in Earth's spheroid, a specialization of triaxial ellipsoid.

Likewise for surface area, either based on a map projection or a geodesic polygon.

[20] In astronomy, the International Astronomical Union denotes the nominal equatorial Earth radius as

Scholars have interpreted Aristotle's figure to be anywhere from highly accurate[23] to almost double the true value.

[24] The first known scientific measurement and calculation of the circumference of the Earth was performed by Eratosthenes in about 240 BC.

Around 100 BC, Posidonius of Apamea recomputed Earth's radius, and found it to be close to that by Eratosthenes,[26] but later Strabo incorrectly attributed him a value about 3/4 of the actual size.

[27] Claudius Ptolemy around 150 AD gave empirical evidence supporting a spherical Earth,[28] but he accepted the lesser value attributed to Posidonius.

His highly influential work, the Almagest,[29] left no doubt among medieval scholars that Earth is spherical, but they were wrong about its size.

The Magellan expedition (1519–1522), which was the first circumnavigation of the World, soundly demonstrated the sphericity of the Earth,[31] and affirmed the original measurement of 40,000 km (25,000 mi) by Eratosthenes.

Around 1690, Isaac Newton and Christiaan Huygens argued that Earth was closer to an oblate spheroid than to a sphere.

However, around 1730, Jacques Cassini argued for a prolate spheroid instead, due to different interpretations of the Newtonian mechanics involved.

[32] To settle the matter, the French Geodesic Mission (1735–1739) measured one degree of latitude at two locations, one near the Arctic Circle and the other near the equator.

The expedition found that Newton's conjecture was correct:[33] the Earth is flattened at the poles due to rotation's centrifugal force.