Earthworm

[clarification needed] Other slang names for earthworms include "dew-worm", "rainworm", "nightcrawler", and "angleworm" (from its use as angling hookbaits).

[2] Earthworms are commonly found in moist, compost-rich soil, eating a wide variety of organic matters,[3] which include detritus, living protozoa, rotifers, nematodes, bacteria, fungi and other microorganisms.

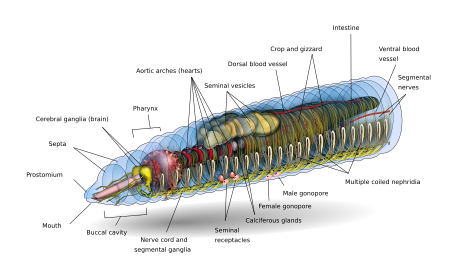

[citation needed] Earthworms have a central nervous system consisting of two ganglia above the mouth, one on either side, connected to an axial nerve running along its length to motor neurons and sensory cells in each segment.

Similar sets of muscles line the gut tube, and their actions propel digested food toward the worm's anus.

[9] Probably the longest worm on confirmed records is Amynthas mekongianus that extends up to 3 m (10 ft) [10] in the mud along the banks of the 4,350 km (2,703 mi) Mekong River in Southeast Asia.

From front to back, the basic shape of the earthworm is a cylindrical tube-in-a-tube, divided into a series of segments (called metameres) that compartmentalize the body.

Furrows are generally[11] externally visible on the body demarking the segments; dorsal pores and nephridiopores exude a fluid that moistens and protects the worm's surface, allowing it to breathe.

An adult earthworm develops a belt-shaped glandular swelling, called the clitellum, which covers several segments toward the front part of the animal.

The posterior is most commonly cylindrical like the rest of the body, but depending on the species, it may also be quadrangular, octagonal, trapezoidal, or flattened.

[15] Interior to the muscle layer is a fluid-filled chamber called a coelom[16] that by its pressurization provides structure to the worm's boneless body.

This arrangement means the brain, sub-pharyngeal ganglia and the circum-pharyngeal connectives form a nerve ring around the pharynx.

From there it is carried through the septum (wall) via a tube which forms a series of loops entwined by blood capillaries that also transfer waste into the tubule of the nephrostome.

Gases are exchanged through the moist skin and capillaries, where the oxygen is picked up by the haemoglobin dissolved in the blood plasma and carbon dioxide is released.

[36] A few species exhibit pseudogamous parthogenesis, meaning that mating is necessary to stimulate reproduction, even though no male genetic material passes to the offspring.

One or more pairs of spermathecae are present in segments 9 and 10 (depending on the species) which are internal sacs that receive and store sperm from the other worm during copulation.

[38] Sex pheromones are probably important in earthworms because they live in an environment where chemical signaling may play a crucial role in attracting a partner and in facilitating outcrossing.

[41] Earthworms travel underground by means of waves of muscular contractions which alternately shorten and lengthen the body (peristalsis).

The shortened part is anchored to the surrounding soil by tiny clawlike bristles (setae) set along its segmented length.

Stephenson (1930) devoted a chapter of his monograph to this topic, while G. E. Gates spent 20 years studying regeneration in a variety of species.

Earthworms are classified into three main ecophysiological categories: (1) leaf litter- or compost-dwelling worms that are nonburrowing, live at the soil-litter interface and eat decomposing organic matter (epigeic) e.g. Eisenia fetida; (2) topsoil- or subsoil-dwelling worms that feed (on soil), burrow and cast within the soil, creating horizontal burrows in upper 10–30 cm of soil (endogeic); and (3) worms that construct permanent deep vertical burrows which they use to visit the surface to obtain plant material for food, such as leaves (anecic, meaning "reaching up"), e.g. Lumbricus terrestris.

[50] Earthworm populations depend on both physical and chemical properties of the soil, such as temperature, moisture, pH, salts, aeration, and texture, as well as available food, and the ability of the species to reproduce and disperse.

Earthworms are preyed upon by many species of birds (e.g. robins, starlings, thrushes, gulls, crows), snakes, wood turtles, mammals (e.g. bears, boars, foxes, hedgehogs, pigs, moles[51]) and invertebrates (e.g. ants,[52] flatworms, ground beetles and other beetles, snails, spiders, and slugs).

Certain species of earthworm come to the surface and graze on the higher concentrations of organic matter present there, mixing it with the mineral soil.

Because a high level of organic matter mixing is associated with soil fertility, an abundance of earthworms is generally considered beneficial by farmers and gardeners.

[54][55] As long ago as 1881 Charles Darwin wrote: "It may be doubted whether there are many other animals which have played so important a part in the history of the world, as have these lowly organized creatures.

[66] The ability to break down organic materials and excrete concentrated nutrients makes the earthworm a functional contributor in restoration projects.

In response to ecosystem disturbances, some sites have utilized earthworms to prepare soil for the return of native flora.

Research from the Station d'écologie Tropicale de Lamto asserts that the earthworms positively influence the rate of macroaggregate formation, an important feature for soil structure.

[68] Nitrogenous fertilizers tend to create acidic conditions, which are fatal to the worms, and dead specimens are often found on the surface following the application of substances such as DDT, lime sulphur, and lead arsenate.

Globally, certain earthworms populations have been devastated by deviation from organic production and the spraying of synthetic fertilizers and biocides, with at least three species now listed as extinct, but many more endangered.