East–West Schism

[1][2][3] Prominent among these were the procession of the Holy Spirit (Filioque), whether leavened or unleavened bread should be used in the Eucharist,[a] iconoclasm, the coronation of Charlemagne as Emperor of the Romans in 800, the Pope's claim to universal jurisdiction, and the place of the See of Constantinople in relation to the pentarchy.

[8][9][10] In 1054, the papal legate sent by Leo IX travelled to Constantinople in order, among other things, to deny Cerularius the title of "ecumenical patriarch" and insist that he recognize the pope's claim to be the head of all of the churches.

The historian Axel Bayer says that the legation was sent in response to two letters, one from the emperor seeking help to organize a joint military campaign by the eastern and western empires against the Normans, and the other from Cerularius.

[1] Still, the Church split along doctrinal, theological, linguistic, political, and geographical lines, and the fundamental breach has never been healed: each side occasionally accuses the other of committing heresy and of having initiated the schism.

[1] The emergence of competing Greek and Latin hierarchies in the Crusader states, especially with two claimants to the patriarchal sees of Antioch, Constantinople, and Jerusalem, made the existence of a schism clear.

In 1965, Pope Paul VI and Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras I nullified the anathemas of 1054,[1] although this was a nullification of measures taken against only a few individuals, merely as a gesture of goodwill and not constituting any sort of reunion.

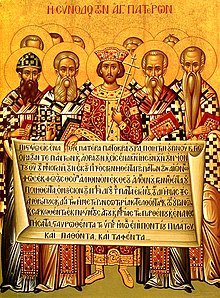

The local church which manifests the body of Christ cannot be subsumed into any larger organisation or collectivity which makes it more catholic and more in unity, for the simple reason that the principle of total catholicity and total unity is already intrinsic to it.The iconoclast policy enforced by a series of decrees of Emperor Leo III the Isaurian in 726–729 was resisted in the West, giving rise to friction that ended in 787, when the Second Council of Nicaea reaffirmed that images are to be venerated but not worshipped.

[68] In contrast, Bishop Kallistos Ware suggests that the problem is more in the area of semantics than of basic doctrinal differences: The Filioque controversy which has separated us for so many centuries is more than a mere technicality, but it is not insoluble.

[91] The Catholic doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, which claims that God protected the Virgin Mary from original sin through no merit of her own,[92][93] was dogmatically defined by Pope Pius IX in 1854.

[100] It was developed in time in Western theology, according to which "all who die in God's grace and friendship, but still imperfectly purified, are indeed assured of their eternal salvation; but after death they undergo purification, so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven.

In Eastern Christendom, the teaching of papal supremacy is said to be based on the pseudo-Isidorian Decretals,[125] documents attributed to early popes but actually forged, probably in the second quarter of the 9th century, with the aim of defending the position of bishops against metropolitans and secular authorities.

[137] Laurent Cleenewerck comments: Victor obviously claimed superior authority, probably from St. Peter, and decided – or at least "attempted" to excommunicate a whole group of Churches because they followed a different tradition and refused to conform.

[citation needed] In 342, Pope Julius I wrote: "The custom has been for word to be written first to us [in the case of bishops under accusation, and notably in apostolic churches], and then for a just sentence to be passed from this place".

[144][145] The Acacian schism, when, "for the first time, West lines up against East in a clear-cut fashion",[146] ended with acceptance of a declaration insisted on by Pope Hormisdas (514–523) that "I hope I shall remain in communion with the apostolic see in which is found the whole, true, and perfect stability of the Christian religion".

"[citation needed] Earlier, in 494, Pope Gelasius I (492–496) wrote to Byzantine emperor, Anastasius, distinguishing the power of civil rulers from that of the bishops (called "priests" in the document), with the latter supreme in religious matters; he ended his letter with: "And if it is fitting that the hearts of the faithful should submit to all priests in general who properly administer divine affairs, how much the more is obedience due to the bishop of that see which the Most High ordained to be above all others, and which is consequently dutifully honoured by the devotion of the whole Church.

[39] Thereafter, the bishop's connection with the imperial court meant that he was able to free himself from ecclesiastical dependency on Heraclea and in little more than half a century to obtain recognition of next-after-Rome ranking from the First Council of Constantinople (381), held in the new capital.

[167] This canon would remain a constant source of friction between East and West until the mutual excommunications of 1054 made it irrelevant in that regard;[173] but controversy about its applicability to the authority of the patriarchate of Constantinople still continues.

Resentment in the West against the Byzantine emperor's governance of the Church is shown as far back as the 6th century, when "the tolerance of the Arian Gothic king was preferred to the caesaropapist claims of Constantinople".

[212] These two letters were entrusted to a delegation of three legates, headed by the undiplomatic cardinal Humbert of Silva Candida, and also including Frederick of Lorraine, who was papal secretary and Cardinal-Deacon of Santa Maria in Domnica, and Peter, Archbishop of Amalfi.

When in 1182 the regency of the empress mother, Maria of Antioch, an ethnic French notorious for the favouritism shown to Latin merchants and the big aristocratic land-owners, was deposed by Andronikos I Komnenos in the wake of popular support, the new emperor allowed mobs to massacre the hated foreigners.

In the 15th century, the eastern emperor John VIII Palaiologos, pressed hard by the Ottoman Turks, was keen to ally himself with the West, and to do so he arranged with Pope Eugene IV for discussions about the reunion to be held again, this time at the Council of Ferrara-Florence.

However, upon their return, the Eastern bishops found their agreement with the West broadly rejected by the populace and by civil authorities (with the notable exception of the Emperors of the East who remained committed to union until the Fall of Constantinople two decades later).

At the time of the Fall of Constantinople to the invading Ottoman Empire in May 1453, Orthodox Christianity was already entrenched in Russia, whose political and de facto religious centre had shifted from Kyiv to Moscow.

Nonetheless, the ecclesial communities which emerged in these historical circumstances have the right to exist and to undertake all that is necessary to meet the spiritual needs of their faithful, while seeking to live in peace with their neighbours.

On a number of occasions, Pope John Paul II recited the Nicene Creed with patriarchs of the Eastern Orthodox Church in Greek according to the original text.

[267] Both he and his successor, Pope Benedict XVI, have recited the Nicene Creed jointly with Patriarchs Demetrius I and Bartholomew I in Greek without the Filioque clause, "according to the usage of the Byzantine Churches".

John Paul II and Bartholomew I explicitly stated their mutual "desire to relegate the excommunications of the past to oblivion and to set out on the way to re-establishing full communion".

John Paul II visited other heavily Orthodox areas such as Ukraine, despite lack of welcome at times, and he said that healing the divisions between Western and Eastern Christianity was one of his fondest wishes.

[280] These doctrinal issues center around the Orthodox perception that the Catholic theologians lack the actual experience of God called theoria and thereby fail to understand the importance of the heart as a noetic or intuitive faculty.

In opposition to what they characterize as pagan, heretical and "godless" foundations, the Orthodox rely on intuitive and mystical knowledge and vision of God (theoria) based on hesychasm and noesis.

476 End of the Western Empire; 550 Conquests of Justinian I; 717 Accession of Leo the Isaurian; 867 Accession of Basil I; 1025 Death of Basil II; 1095 Eve of the First Crusade; 1170 Under Manuel I; 1270 Under Michael VIII Palaiologos; 1400 Before the fall of Constantinople