Eastern Roman army

In the 7th century, Emperor Heraclius led the East Roman army against the Sasanian Empire, temporarily regaining Egypt and Syria, and then against the Rashidun Caliphate.

These compilations of Roman laws dating from the 4th century contain numerous imperial decrees relating to the regulation and administration of the late army.

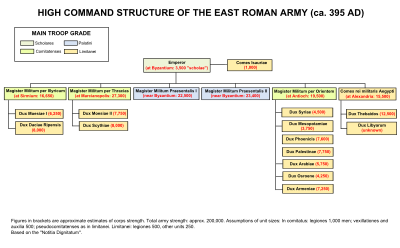

In 395, the death of the last sole Roman emperor, Theodosius I (r. 379–395 AD), led to the final split of the empire into two political entities, the West (Occidentale) and the East (Orientale).

[citation needed] Constantine's massive reconstruction of the city of Byzantium into Constantinople, a second capital to rival Rome, led to the establishment of a separate eastern court and bureaucracy.

Finally, the political split became complete with the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the early 5th century and its replacement by a number of barbarian Germanic kingdoms.

[citation needed] The Eastern Roman Empire and army, on the other hand, continued with gradual changes until the Persian and later Arab invasions in the 7th century.

[7] The higher end of the range is provided by the late 6th-century military historian Agathias, who gives a global total of 645,000 effectives for the army "in the old days", presumed to mean when the empire was united.

[18] However, the intrigues and political ambitions of their commanders (The Counts of the Excubitors, rendered in Latin as comes excubitorum) such as Priscus during the reigns of the emperors Maurice, Phocas and Heraclius and the Count Valentinus during the reign of Emperor Constans II, doomed Leo I's formerly famed Isaurian unit to obscurity.

[22] They were outside the normal military chain of command as they did not belong to the comitatus praesentales and reported to the magister officiorum, a civilian official.

15% were heavily armoured shock charge cavalry: cataphracti and clibanarii[14] The limitanei garrisoned fortifications along the borders of the Roman Empire.

However, during the 6th century the power wielded by these dukes diminished meaning that many of the limitanei became part-time soldiers who supported their income usually through agricultural labour.

[35] The role of the limitanei appears to have included garrisoning frontier fortifications, operating as border guards and customs police, and preventing small-scale raids.

[40] These regions continued to be the prime recruiting grounds for the Eastern Roman army e.g. the emperor Justin I (r. 518-27), uncle of Justinian I, was a Latin-speaking peasant who never learnt to speak more than rudimentary Greek.

According to the Strategikon, the cavalry soldiers should have long "Avar" tunics reaching past the knees, and large cloaks with sleeves.

[52] In the 1st and 2nd centuries, a Roman soldier's clothes consisted of a single-piece, short-sleeved tunic whose hem reached the knees and special hobnailed sandals (caligae).

This attire, which left the arms and legs bare, had evolved in a Mediterranean climate and was not suitable for northern Europe in cold weather.

[54] Late Roman clothing was often highly decorated, with woven or embroidered strips, clavi, and circular roundels, orbiculi, added to tunics and cloaks.

These decorative elements usually consisted of geometrical patterns and stylised plant motifs, but could include human or animal figures.

[55] A distinctive part of a soldier's costume, though it seems to have also been worn by non-military bureaucrats, was a type of round, brimless hat known as the pannonian cap (pileus pannonicus).

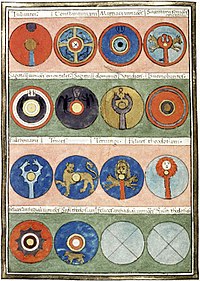

For example, illustrations in the Notitia show that the army's fabricae (arms factories) were producing mail armour at the end of the 4th century.

[59] The cataphract and clibanarii cavalry, from limited pictorial evidence and especially from the description of these troops by Ammianus, seem to have worn specialist forms of armour.

In particular their limbs were protected by laminated defences, made up of curved and overlapping metal segments: "Laminarum circuli tenues apti corporis flexibus ambiebant per omnia membra diducti" (Thin circles of iron plates, fitted to the curves of their bodies, completely covered their limbs).

Cheek-guards could often be fastened together over the chin to protect the face, and covered the ears save for a slit to permit hearing e.g. the "Auxiliary E" type or its Niederbieber variant.

Cavalry helmets became even more enclosed e.g. the "Heddernheim" type, which is close to the medieval great helm, but at the cost much reduced vision and hearing.

[62] In contrast, some infantry helmets in the 4th century reverted to the more open features of the main Principate type, the "Imperial Gallic".

[64][65] Despite the apparent cheapness of manufacture of their basic components, many surviving examples of Late Roman helmets, including the Intercisa type, show evidence of expensive decoration in the form of silver or silver-gilt sheathing.

[80] At the same time, infantry acquired a heavy thrusting-spear (hasta) which became the main close order combat weapon to replace the gladius, as the spatha was too long to be swung comfortably in tight formation (although it could be used to stab).

[84] In addition to his thrusting-spear, a late foot soldier might also carry a throwing-spear (verutum) or a spiculum, a kind of heavy, long pilum, similar to an angon.

Late infantrymen often carried half a dozen lead-weighted throwing-darts called plumbatae (from plumbum = "lead"), with an effective range of c. 30 m (98 ft), well beyond that of a javelin.

[88] In the 7th century, the emperor Heraclius led the east Roman army against the Sassanid Empire, temporarily regaining Egypt and Syria, and then against the Rashidun Caliphate.