Easter egg

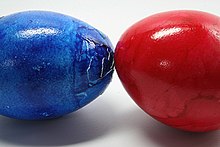

The oldest tradition, which continues to be used in Central and Eastern Europe, is to dye and paint chicken eggs.

[3][4][5] In addition, one ancient tradition was the staining of Easter eggs with the colour red "in memory of the blood of Christ, shed as at that time of his crucifixion.

[7][17][6][8][9] The Christian Church officially adopted the custom, regarding the eggs as a symbol of the resurrection of Jesus, with the Roman Ritual, the first edition of which was published in 1610 but which has texts of much older date, containing among the Easter Blessings of Food, one for eggs, along with those for lamb, bread, and new produce.

[8][9] Lord, let the grace of your blessing + come upon these eggs, that they be healthful food for your faithful who eat them in thanksgiving for the resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ, who lives and reigns with you forever and ever.Sociology professor Kenneth Thompson discusses the spread of the Easter egg throughout Christendom, writing that "use of eggs at Easter seems to have come from Persia into the Greek Christian Churches of Mesopotamia, thence to Russia and Siberia through the medium of Orthodox Christianity.

[6][7] Peter Gainsford maintains that the association between eggs and Easter most likely arose in western Europe during the Middle Ages as a result of the fact that Catholic Christians were prohibited from eating eggs during Lent, but were allowed to eat them when Easter arrived.

[10][11] A common practice in England in the medieval period was for children to go door-to-door begging for eggs on the Saturday before Lent began.

During Lent, since chickens would not stop producing eggs during this time, a larger than usual store might be available at the end of the fast.

Some Christians symbolically link the cracking open of Easter eggs with the empty tomb of Jesus.

[20] In the Orthodox churches, Easter eggs are blessed by the priest at the end of the Paschal Vigil (which is equivalent to Holy Saturday), and distributed to the faithful.

[3][4] Similarly, in the Roman Catholic Church in Poland, the so-called święconka, i.e. blessing of decorative baskets with a sampling of Easter eggs and other symbolic foods, is one of the most enduring and beloved Polish traditions on Holy Saturday.

In Greece, women traditionally dye the eggs with onion skins and vinegar on Thursday (also the day of Communion).

[22][23] In Egypt, it is a tradition to decorate boiled eggs during Sham el-Nessim holiday, which falls every year after the Eastern Christian Easter.

In the North of England these are called pace-eggs or paste-eggs, from a dialectal form of Middle English pasche.

King Edward I's household accounts in 1290 list an item of 'one shilling and sixpence for the decoration and distribution of 450 Pace-eggs!

In more recent centuries in England, eggs have been stained with coffee grains[25] or simply boiled and painted in their shells.

[28] The tradition to dyeing the easter eggs in an Onion tone exists in the cultures of Armenia, Bulgaria, Georgia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, Czechia, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Israel.

[30][31] When boiling them with onion skins, leaves can be attached prior to dyeing to create leaf patterns.

[35] Decorating eggs for Easter using wax resistant batik is a popular method in some other eastern European countries.

This also happens in Georgia, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, North Macedonia, Romania, Russia, Serbia and Ukraine.

Cascarones, a Latin American tradition now shared by many US States with high Hispanic demographics, are emptied and dried chicken eggs stuffed with confetti and sealed with a piece of tissue paper.

In the United Kingdom, Germany, and other countries children traditionally rolled eggs down hillsides at Easter.

[42] In 1878, Hayes was approached by many young Easter Egg rollers who asked for the event to be held at the White House.

The annual egg jarping world championship is held every year over Easter in Peterlee, Durham.

In parts of Europe it is also called epper, presumably from the German name Opfer, meaning "offering" and in Greece it is known as tsougrisma.

In the Greek Orthodox tradition, red eggs are also cracked together when people exchange Easter greetings.

[56][57][58][59] In the Indian state of Goa, the Goan Catholic version of marzipan is used to make easter eggs.

The jewelled Easter eggs made by the Fabergé firm for the two last Russian Tsars are regarded as masterpieces of decorative arts.

Dark red eggs are a tradition in Greece and represent the blood of Christ shed on the cross.

The ancient Zoroastrians painted eggs for Nowruz, their New Year celebration, which falls on the Spring equinox.

In fact, modern scholarship has been unable to trace any association between eggs and a supposed goddess named Ostara before the 19th century, when early folklorists began to speculate about the possibility.